As Latter-day Saints prepare to celebrate the 175th anniversary of Pioneer Day on July 24th this year, LDS Living recognizes that in addition to the sacrifices of the early pioneers, there are many modern-day pioneers across the globe who have build the Church in their nations or in their families. This story originally ran in 2018 but is being republished as a way to celebrate the story of a true pioneer.

Several days before embarking on the ship Julia Ann, Australian Latter-day Saint John Perkins wrote in his diary: “Monday 3rd September 1855: The brethren and sisters are beginning to come in to go by the Julia Ann or the port of San Francisco.” This ill-fated adventure would be a singular event in Mormon history because it would be the only known shipwreck that claimed the lives of multiple Mormon pioneers on their way to Zion.

At the time of departure, there were a total of 56 aboard the Julia Ann, half of whom were Latter-day Saints, including three Mormon crewmembers. Augustus Farnham had appointed Elder John Penfold Sr. to be in charge of the company. As the Saints left the Sydney docks, they were singing “The Gallant Ship Is Under Weigh,” a hymn written by the famous LDS poet and hymn writer W. W. Phelps.

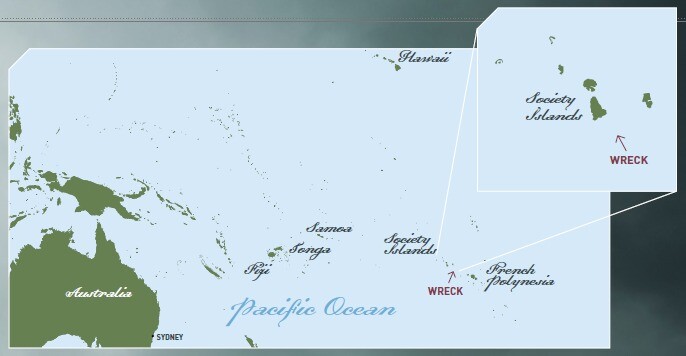

Captain Benjamin F. Pond recalled, “The first two weeks at sea were altogether exceedingly unpleasant; head winds, accompanied with much rain. We however entered the south-east trades, and everything again brightened, promising a speedy and pleasant voyage.” Indeed, the voyage began pleasantly enough, but on October 4th, nearly a month into their travels, the ship began picking up speed while passing between Mopea and the Scilly Isles.

DISASTER STRIKES

The following passenger accounts depict the unexpected and horrifying outcome of this “pleasant” voyage.

Latter-day Saint passenger John McCarthy recalled:

"The log was [heaved] about 8 o’clock p.m., and the bark was found to be making 11½ knots per hour; shortly afterwards the sea became broken, and in about an half an hour the vessel, with a tremendous crash, dashed head on to a coral reef."

Andrew Anderson, the second missionary to Australia in the early 1840s and a Julia Ann passenger, recounted:

"About half-past eight o’clock she [the Julia Ann] struck on a reef. . . . Word came out from someone for the passengers to go to the cabin, and by the time I got the four children out of bed, the water was knocking about the boxes. I got my leg very much bruised with a large box, with difficulty we gained the cabin, and about ten minutes after we left, house, gally, and box was all over board, preparations were made to go on the rocks to ascertain whether we could get any footing, as there was no land in sight, the ship was breaking up fast."

In her report to the San Francisco Daily Herald, actress Esther Spangenberg said the man who was at the helm at the time of the wreck was Mr. Coffin, a man with a rather ominous name. She added,

“The night was dark, neither moon or stars visible, when suddenly the chief officer called out to the man at the wheel, ‘Hard down your helm,’ and in an instant after the ship struck on a reef, from which she rebounded, and afterwards we could hear her bottom grate harshly on the rocks. The Captain . . . rushed on deck, but before he could reach it the ship was completely fast on the reef.”

Spangenberg further described in detail the great confusion that immediately followed:

“The steerage passengers rushed into the cabin—mothers holding their undressed children in their arms, as they snatched them from their slumbers, screaming and lamenting, when their fears were in some measure allayed by a sailor who came to the cabin for a light and told them that, although the ship would be lost, their lives would be saved, as we were close to the reef.”

At this time of great urgency, Captain Pond “called for a volunteer to attempt to reach the reef by swimming with a small line. One of the sailors instantly stripped; the log line was attached to his body, and he succeeded in swimming to the reef. … By this means a larger line was hauled to the reef, and made fast to the rocks.” Further, “I commenced the perilous task of placing the women and children upon the reef. A sailor in a sling upon the rope, took a woman or a child in his arms, and was hauled to the reef by those already there. … The process was an exceedingly arduous one, and attended with much peril.”

LIVES LOST AT SEA

Captain Benjamin F. Pond

Captain Pond emotionally recalled witnessing a terrified Mormon mother frantically crying out for her teenage daughter who had just escaped to the reef. The young girl’s sister had already been washed off the deck and drowned.

“There was a large family on board named ‘Anderson’ a father, mother, three daughters, two sons and an infant. One daughter, a pretty girl, ten years of age, was washed off the deck shortly after the ship struck, and drowned; another daughter ‘Agnes,’ 16 years old, had escaped to the reef, the rest of the family were still on board.”

Latter-day Saint passenger Peter Penfold also told of this harrowing experience that claimed a total of five lives:

“Sister [Martha] Humphries, and sister [Eliza] Harris and infant, were drowned in the cabin. Little Mary Humphries and Marian Anderson were washed off the [deck] and drowned. . . After I had helped to get them all out of the cabin, I came up and found the vessel all broken into fragments, except the cabin, and into that the water was rushing at a furious rate, sweeping out all the partitions.”

Church member John McCarthy wrote that he had engraved on his memory “mothers nursing their babes in the midst of falling masts and broken spars, while the breakers were rolling 20 feet high over the wreck.” He recalled that some of the men clung to the wreckage. “Soon afterwards the vessel broke to pieces, and the part they were on was providentially carried high upon the rocks, and they were landed in safety.”

STRUGGLING TO SURVIVE

The courageous, steady character of Captain Pond, who was both an owner and a master of the vessel, was displayed during this entire ordeal. Pond also described in vivid detail the dire predicament when they finally reached the coral reef:

"It was about 11 o’clock at night when all were landed; we were up to our waists in water, and the tide rising. Seated upon the spars and broken pieces of the wreck, we patiently awaited the momentous future. Wrapped in a wet blanket picked up among the floating spars, I seated myself in the boat, the water reaching to my waist; my legs and arms were badly cut and bruised by the coral. Though death threatened ere morning’s dawn, exhausted nature could bear up no longer, and I slept soundly. ’Twas near morning when I awoke. The moon was up and shed her faint light over the dismal scene; the sullen roar of the breakers sent an additional chill through my already benummed frame. The bell at the wheel, with every surge of the sea, still tolled a knell to the departed, and naught else but the wailings of a bereaved mother broke the stillness of the night."

When sunlight broke at dawn, land was discovered about 10 miles away. A rowboat was patched up, and spars and drift wood were assembled to make a raft. The women and children were placed in the boat, led by Mr. Coffin, while the men were forced to remain on the reef for a second miserable night. Finally, in a state of complete exhaustion, having had no drink or food for two full days and despite the sharks lurking nearby, these men reached the island safely. Upon reaching shore, children quickly escorted the men to drinking water, which had come from holes dug beneath the coral sand.

Three days later, Pond led an exploring party to look for more provisions to sustain the castaways. On another island, some eight miles from their main camp, he found a much-needed coconut grove. Turtles were also found to lay eggs on the island at night.

Pond noted, “Our hearts dilated with gratitude, for without something of this kind our case would have been indeed desperate. Our living now consisted of shell fish, turtle, sharks and cocoa nuts. We also prepared a garden, and planted some pumpkins, peas and beans.” Latter-day Saint Charles Logie described how pancakes were made by grating the coconuts and mixing them with turtle eggs. John McCarthy added that “too much cannot be said in commendation of the Saints in this trying situation. I have seen an old lady upwards to 60 years of age out at night hunting turtle.” Further, “while on the uninhabited islands we held our regular meetings, dividing the time between worship and labor as we have done had we been at our ordinary occupations.”

With an established routine and provisions now stabilized, the next step for deliverance was to repair the quarter boat. The crew used great ingenuity in pulling strewn materials together in order to construct both a forge and a bellows so that nails could be made and ironwork produced.

The survivors were also divided into family units; each group built thatched huts using leaves from the pandanus tree. McCarthy noted,

“After we were all landed on the island, Captain Pond called all hands to order, and delivered a short address, stating that as we were cast away upon a desolate island, that a common brotherhood should be maintained, and that every man should hunt birds and fish for our common sustenance, to which proposition all assented.”

Five weeks later, the boat was ready for launching. The craft was not very sturdy, but there was no alternative; it was either make an effort to escape or remain trapped on the desolate reef.

The Society Islands were the nearest inhabited land, a little over 200 miles away—against the wind. Because of this, Pond decided to go with the wind and attempt to reach the Navigator Islands (Samoa), though their distance was about 1,500 miles away. Three days were spent looking for the best place to launch their feeble craft, and by that time, devastation set in; the weather changed, and a tornado swept the quarter boat away.

The hopelessness was so great that “some threw themselves in despair upon the beach; the silent tear trickled down the cheeks of speechless women; others moaned aloud at their sad, sad fate, for our provisions were nearly exhausted, and starvation stared us in the face.” Fortunately, the craft was eventually recovered, without major damage.

A MIRACULOUS RESCUE

After nearly two months of being stranded on the Scilly Islands, the weather suddenly changed its course and blew toward Samoa, which Pond recognized as “Divine Providence.” Soon every person was recruited to carry the craft about 200 yards across land, where it could be placed on the incoming breakers. It was launched with a crew of 10 brave men who would need to row continuously for several days, both day and night.

The crew had few provisions—merely some salted pork and a little turtle, along with two casks of water. One of the crew, Church member John McCarthy, claimed to have had two dreams, which ultimately led to the rescue. One of his dreams made known that if the 10-man crew voyaged to Samoa, they would drown, but the other revealed that if they rowed toward the Society Islands (Bora Bora), they would be saved.

After finally reaching Bora Bora in late November, the crew was so exhausted they did not have the strength to walk after natives helped them from their makeshift boat. Captain Pond went for help and eventually found it at the British Consulate. They recommended Captain Latham whose vessel, the Emma Packer, was awaiting a shipment of oranges. Captain Latham offered the use of his ship for the rescue voyage, and on December 3, the remaining castaways on Scilly Island were saved.

After spending two months on an uninhabited island, the rescued passengers could not contain their gratitude. Recalling this joyful, redemptive event, John S. Eldredge said,

“I need not attempt to describe our feelings of gratitude and praise which we felt to give the God of Israel for His goodness and mercy in thus working a deliverance for us; for I have not language to express my own feelings, much less the feelings of those around me, suffice it to say, I am thankful to know that His mercy endureth forever.”

This testimony seems to echo the words of the Psalmist who wrote, “He maketh the storm a calm . . . he bringeth them unto their desired haven. Oh that men would praise the Lord for his wonderful works to the children of men!” (Psalms 107:29-31).

EPILOGUE

What became of the Saints after they were rescued? Elders Graham and Eldredge chose not to travel directly back home to Utah but rather took a detour when they came into port in Honolulu on March 12, 1856. They traveled over to Lahaina to meet with Utah missionaries stationed there as part of the Hawaiian Mission. The Anderson and Penfold families chose to settle in California and are later listed as members of the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (known today as the Community of Christ).

While the paths of all the surviving Latter-day Saints are not known, we do know that Graham, Eldredge, and others eventually reached their home in Zion. John McCarthy immigrated to Utah, married his neighbor Eliza Telford, and moved to Bountiful, Utah. The Logie family eventually made their way to American Fork, Utah, and now have a large Mormon posterity.

Did the Mormon converts aboard the ill-fated Julia Ann voyage regret the trip when tragedy arose and five lives were lost? Perhaps this question can best be answered by the additional witness of two of the passengers, one who barely survived and the other who lost her life. Their letters exemplify the faith and fortitude so common among the Saints who attempted to follow inspired counsel to gather to Zion.

Writing to his son from Tahiti, survivor Peter Penfold noted after reaching the island,

“Father and mother and we all are in good health and spirits, though we have lost all our worldly goods, and all that we had; yet we have faith in God and trust He will deliver us soon from this place. . . . Though we were shipwrecked, that is no reason you should be. I hope to see you all before long in the land of the free, surrounded by the saints of the Most High God.”

The other letter was penned by Martha Humphries before her departure from Australia aboard the Julia Ann and her subsequent drowning:

"And now my dear mother, I will answer that question you put me, of when, are we going. . . . We leave Australia, with all its woes, and bitterness, for the Land of Zion next April. . . . Perhaps you will say, I am building on worldly hopes, that never will be realized, not So, Mother . . . knowing what I know, I tell you, if I knew for a positive certainty, that when we get there, persecutions, such as have been the portion of the Saints before, awaited us, I would Still insist upon going, what are a few Short years in this present state, compared with Eternal Life."

Editor’s note: All quotations are reproduced in their original format, including typographical and spelling errors.

To learn more, pick up the DVD and book combo pack of Divine Providence: The Wreck and Rescue of the Julia Ann by Fred E. Woods, now available at Deseret Book.