Although her appearance in the New Testament is brief (only 38 words) and she is unnamed there, Pontius Pilate’s wife is known for her attempt to prevent her husband’s involvement in the death of Jesus of Nazareth. As a Roman, she lived in Caesarea but seems to have accompanied her husband to Jerusalem and may have become acquainted there with aspects of Jewish culture. Later histories record her name as Procla, or perhaps Claudia Procla, and suggest she was a God-fearer or perhaps even a proselyte to Judaism. Subsequent Christian myths magnify and embellish her support for Christians. The scriptural text, however, highlights her sensitivity to spiritual promptings through dreams and her courage to speak out against unjust punishment.

PROCLA’S PLACE OF RESIDENCE

When in Jerusalem, the governor Pilate and Procla likely resided in the palace that Herod the Great built on the west side of the city, near the present-day Jaffa Gate. Their permanent residence would have been in Caesarea at Herod’s exquisite palace on the manmade promontory that jutted into the Mediterranean Sea. The scriptures do not mention them in connection with Caesarea, however, but only their being in Jerusalem during Passover.

The New Testament provides no explanation for Procla’s cognizance of Jesus to lead to her having a dream about him. As a Roman, Procla would likely have been unfamiliar with Jewish customs before her husband received his assignment to govern Judea. Although her dream may have been an inspired, one-time occurrence, it may also indicate an existing familiarity with Jewish issues or an awareness of Jesus before his trial. Even though both Greek and Roman traditions expected women to be modest and heed their husbands’ commands, influential and strong women often privately counseled their husbands to behave in a more moral fashion. Pilate’s wife is a New Testament example of this type of influence when she advised him against involvement in the vendetta against Jesus.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

According to the Byzantine historian John Malalas (Chron 10.14.1) and the apocryphal work Paradosis Pilati, the name of Pilate’s wife was Procla.1 She is only mentioned in relation to her husband, Pontius Pilate, so background from her husband’s life and policies in the Jewish territories provides some context for her surroundings. Pontius Pilate was appointed governor of Judea (A.D. 26–36) under Tiberius Caesar. According to Josephus, Pilate was especially insensitive and oppressive toward the Jews, seeking to abolish their peculiar laws and offending them by displaying in Jerusalem imperial banners bearing the image of Caesar (Ant 18.3.1; War2.9.2). The powerful treasurer of the Jewish temple apparently agreed to some of the Roman governor’s projects because Pilate used temple funds to build an aqueduct to Jerusalem.

Josephus notes that Pilate killed the Jews who protested his building decisions (Ant 18.3.2; War 2.9.4) and mistook as a threat to the peace a number of Samaritans who were seeking for vessels around Mount Gerizim that they believed had been buried by Moses. He sent troops in to break up the crowds, killing many in the melee. Later protests resulted in Pilate’s dismissal from office in A.D. 36 (Ant 18.4.1). The Jewish client-king who was appointed a few years later to oversee Jerusalem, Herod Agrippa I, described Pilate to his friend the emperor Caligula as “naturally inflexible, a blend of self-will and relentlessness” (Embassy 301).

PROCLA’S APPEARANCE IN THE NEW TESTAMENT STORY

Procla’s dream and concern for Jesus. In the final scenes leading up to the crucifixion of Christ, only Matthew recounts Procla’s involvement. On the morning of the crucifixion, Jewish “chief priests and elders” took Jesus, charged with treason against Rome, to stand before Pilate, the governor of Judea. Pilate could not find cause for executing Jesus. He knew the Jewish leaders were accusing Jesus out of “envy,” so he sought to defuse the contention by offering to release a prisoner, whether Jesus or Barabbas, as a Passover gift to the people, as was his custom. While Pilate sat in the “judgment seat,” Procla sent word to him: “Have thou nothing to do with that just man: for I have suffered many things this day in a dream because of him” (Matt. 27:19). Having been warned in a dream of Jesus’ innocence, she warned her husband to show mercy to the accused.

The impressions she received through her dream were motivating enough to cause her to intervene at a most public and formal moment in the proceedings—when Pilate was seated in the chair of judgment. She was willing to ignite her husband’s fiery temper by causing him to be interrupted to advise him against his decision. In the apocryphal Acts of Pilate, after receiving Procla’s warning but before he told the Jewish delegation of it, Pilate explained, “You know that my wife is pious and prefers to practice Judaism with you” to which the Jews answered, “Yes, we know it” and then told them about Procla’s dream (2.1). When nothing he said or did changed their minds, Pilate “washed his hands before the multitude” and, describing Jesus as Procla had done, said, “I am innocent of the blood of this just person,” thereby consenting to their request (Matt. 27:20–24). Whether Procla was indeed inclined toward Judaism or later to Christianity is not verifiable from other sources.

Revelation through dreams. Matthew’s Gospel opens with stories that show how God’s revelations through dreams are trustworthy. The magi were warned not to return to Herod, Joseph was instructed to take Mary and Jesus to Egypt, and he was told when it was safe to return to Judea from Egypt—all three revelations communicated to these men in the form of dreams (Matt. 2:12–13, 19–20). Toward the end of his Gospel, Matthew again demonstrates the communication of God through a dream, but this time a woman was the recipient of the revelation. Whether all she learned about Jesus came solely from that dream or whether she had previous information to indicate that he was “just” or righteous is not clear from the passage. What is clear is that she took a stand to communicate the dream’s message.

The scriptures also cite her words sent to Pilate, not a paraphrase. The dream and its poignant message caused her “[to suffer] many things this day” because of what she had learned through the revelation (Matt. 27:19). One of the costs of true discipleship with the Savior involves suffering, drinking from the same “cup” of affliction that he drank (Rom. 8:17–18; Matt. 20:22), because “without sufferings [we] cannot be made perfect” (JST, Heb. 11:40). The dream produced such discomfort as to propel Procla to act, even to plead for Jesus, whereas the Jewish leaders pleaded for Barabbas. How her suffering informed her thoughts and actions after the death and Resurrection of Jesus remains unknown.

Lead image from lds.org

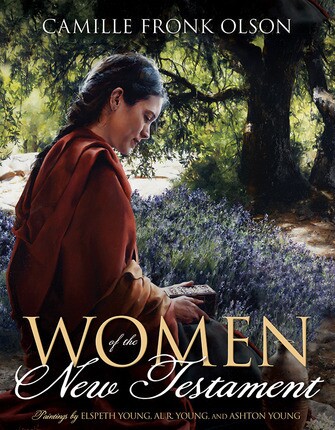

During his mortal ministry, the Lord Jesus Christ loved, taught, healed, and interacted with numerous women. More than fifty specific women are introduced in the New Testament, with multitudes of others numbered among the Savior's followers. Whether these women were identified individually by name or simply mentioned as a devout follower in the crowd, their stories of sacrifice and eager service have rich meaning and application for our lives today.

In this well-researched and richly illustrated companion volume to Women of the Old Testament, author Camille Fronk Olson focuses on many of these remarkable women and explores the influence of Jesus Christ and his gospel on women living in the meridian of time.