1. The founder of the program experienced a crisis of faith during his schooling.

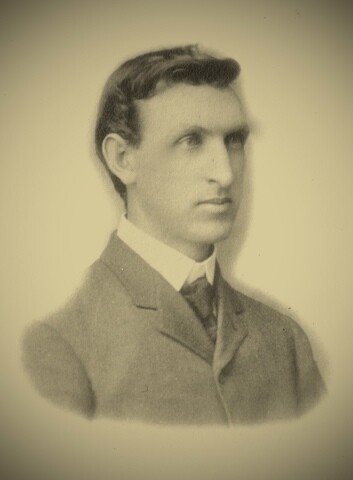

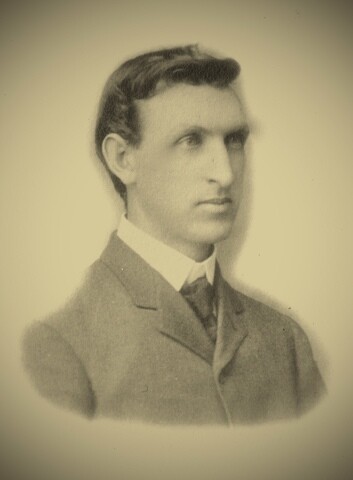

Joseph F. Merrill, a professor of physics at the University of Utah, was serving as the second counselor in the presidency of the Granite, Utah Stake when he first conceived of the seminary program. Merrill was one of the first Latter-day Saints to receive a Ph.D., studying at the University of Michigan, the University of Chicago, Cornell, and Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. During his graduate studies, he experienced a crisis of faith, writing to his fiancé back home, “It’s a little amusing to see some pious people; they seem to think religion consists principally in going to church. But I must confess that judged by this standard I have lost nearly all of my religion . . . What do you think will become of me!”[1]

Merrill was helped through his faith crisis by his fiancé, Annie Laura Hyde, the granddaughter of Church president John Taylor and Apostle Orson Hyde. When he returned to Utah and married, Merrill began a long tenure of Church service that eventually resulted in the creation of the seminary program, the launch of the Institutes of Religion, and a long tenure as a member of Quorum of the Twelve. During his service in the Twelve, he served as president of the European Mission where he mentored a young missionary named Gordon B. Hinckley.[2] Merrill later commented to his daughter that he was partially inspired to create the seminary program by some of the religion seminars offered to the students during his studies there.

2. A young mother teaching her children partially inspired the creation of the seminary program.

Besides the seminary program, another unique practice developed by the Granite Stake was Family

Home Evening. The program started in the Granite Stake and was introduced to the entire Church in a letter sent to Church leaders in 1915.[3] During one of the stake sponsored family nights, Merrill was intrigued by the stories his wife Laura shared with their children from the Bible and the Book of Mormon. Merrill recalled, “Her list of these stories was so long that her husband often marveled at their number, and frequently sat spellbound as were the children as she skillfully related them.”[4] When Merrill asked his wife where she had learned to teach these stories, she spoke of attending James E. Talmage’s religion class at the Salt Lake Stake Academy. Inspired by his wife’s teaching Merrill formulated a plan to bring religion to students in public high schools without violating established barriers between Church and state.

3. The founders of the program thought that it might fail.

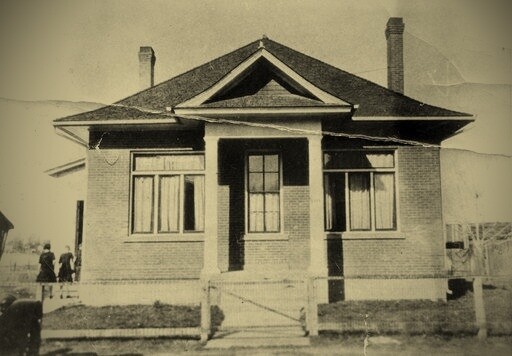

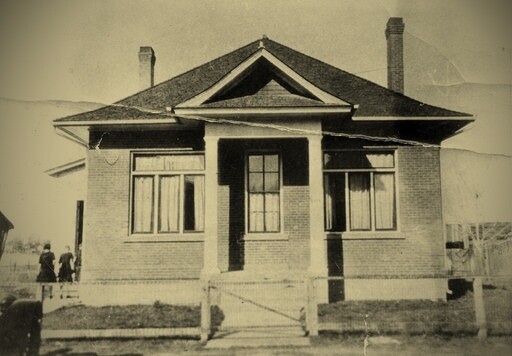

The first seminary building, built at a cost of $2,500, was begun a few weeks before the beginning of the school year in 1912. The building consisted of four rooms—a cloakroom, an office, a small library, and a classroom. Furnishings in the classroom consisted of blackboards, armrest seats, and a stove for heat. There were no lights and no text books other than the scriptures. The library consisted of a Bible dictionary owned by Thomas Yates. Seminary students were expected to make their own maps of the Holy Land, North America, South America, Mesopotamia, and Arabia.[5]

The building was built across the street from Granite High School in Salt Lake City and looked very

much like one of the small bungalow homes common in the era. According to the physical facilities department of Seminaries and Institutes, the building was constructed to look like a home so that if the new venture failed the Church could sell the building a recoup part of its losses. Instead, the seminary was expanded and parts of the original building remained in service until 1993, when the original structure was torn down and replaced with a new building. Granite High School closed in 2009, but the Granite Seminary continued to serve as a home for S&I programs for deaf students.[6]

4. The first seminary teacher only taught for one year.

In seeking the right teacher for his seminary program, Joseph F. Merrill sent a letter to the Church Board of Education, outlining expectations for the teacher, writing, “May I suggest it is the desire of the presidency of the stake to have a strong young man who is properly qualified to do the work in a most satisfactory manner. By young we do not necessarily mean a teacher who is young in years, but a man who is young in his feelings, who loves young people, who delights in their company, who can command their respect and admiration and exercise a great influence over them.”[7] The teacher selected to head the first seminary class was Thomas J. Yates, a member of the Granite Stake high council. Yates was not a professional educator but was a highly respected member of the Granite Stake High Council. He already had a full-time position as a construction engineer at the nearby Murray power plant.[8]

When the first seminary opened in the fall of 1912, 70 students enrolled. As for Yates, he spent his mornings working at the Murray power plant and his afternoons at the seminary building. His salary for the first year was $100 a month. At the end of that first year, President Taylor urged Yates to continue teaching. The strain of riding his horse every day from Murray to the Granite seminary building had proven to be too much for Yates and he declined the offer. Among the students who attended seminary at Granite that first year was Mildred Bennion, the mother of President Henry B. Eyring. President Eyring later said of Thomas Yates, “Somehow that one seminary teacher cared enough about her and prayed fervently enough over that young girl that the Spirit put the gospel down into her heart. That one teacher blessed tens of thousands because he taught just one girl in a crowd of 70.[9]

5.The international growth of the seminary program was “explosive.”

The program at Granite was experimental, but it soon caught on and by the 1920s seminaries became widespread throughout the Church. The second seminary was opened in Brigham City in 1915 with Abel S. Rich as the teacher. Before he retired nearly a half century later, Brother Rich trained a new seminary teacher named Boyd K. Packer. In the 1950s the first early morning seminary programs were launched in Southern California and soon spread throughout the United States and Canada.

During the late 1960s and 1970s, the seminary program spread rapidly into other countries where the Church was established. Typical practice during this era was to select an American teacher who would travel to a given country with instructions to set up the program, establish a good relationship with local leaders, train a replacement from the local Church membership, and then return to the United States. Typically these assignments lasted three years. In just the short span of a few years, Seminary & Institutes programs were set up in dozens of nations.

Elder Joe J. Christensen, who headed the program under the direction of Commissioner Neal A. Maxwell, later commented, “It really was an explosive growth period . . . I think the Lord was behind that. I think he wanted those young people to learn the gospel and many things fell into place. It went far beyond what we would have anticipated.”[10] Today Seminary and Institute classes are held in over 250 countries and territories, serving over 740,000 students. S&I programs employ over 3,000 full-time teachers, staff, and administrators, but the vast majority of seminary teachers, over 44,000 are part time volunteers, just like the first seminary teacher, Thomas J. Yates.[11]

To hear more interesting stories about the early days of the Seminary program, listen to “Schooling and Being Schooled in Religious Education” on the LDS Perspectives Podcast.

All images courtesy of Casey Paul Griffiths

Casey Paul Griffiths is one of the authors of By Study and Also By Faith: One Hundred Years of Seminaries and Institutes. His most recent book is What You Didn’t Know About the 100 Most Important Events in Church History(with Susan Easton Black and Mary Jane Woodger).

[1] Joseph F. Merrill to Annie Laura Hyde, June 14, 1896, Baltimore, MD, Joseph F. Merrill Collection, Box 14, Fd. 2, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Brigham Young University.

[2] See Sheri L. Dew, Go Forward With Faith: The Biography of Gordon B. Hinckley, (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1996), 71-73.

[3] Joseph F. Smith, Anthon H. Lund, and Charles W. Penrose, “Home Evening,” Improvement Era, June 1915, 733-734.

[4] Merrill, “A New Institution in Religious Education,” Improvement Era, January 1938, 55.

[5] Coleman and Jones, History of Granite Seminary, 1933, 32.

[6] “Granite Seminary: Spanking New Building Now Stands Where First Classes Were Held in 1912,” Church News, Sept. 4, 1993, 8-9, see also Casey Paul Griffiths, “A Century of Seminary,” Religious Educator, 13:3, 2012, 50-51.

[7] Merrill, “A New Institution in Religious Education,” Improvement Era, January 1938, 55.

[8] Yates, Autobiography, 79.

[9] Eyring, “To Know and Love God,” Address to CES Religious Educators, 5, February 26, 2010.

[10] Joe J. Christensen interview with E. Dale LeBaron, 22-23. Copy in author’s possession.

[11] Seminary and Institutes of Religion Annual Report for 2015, 2-3.