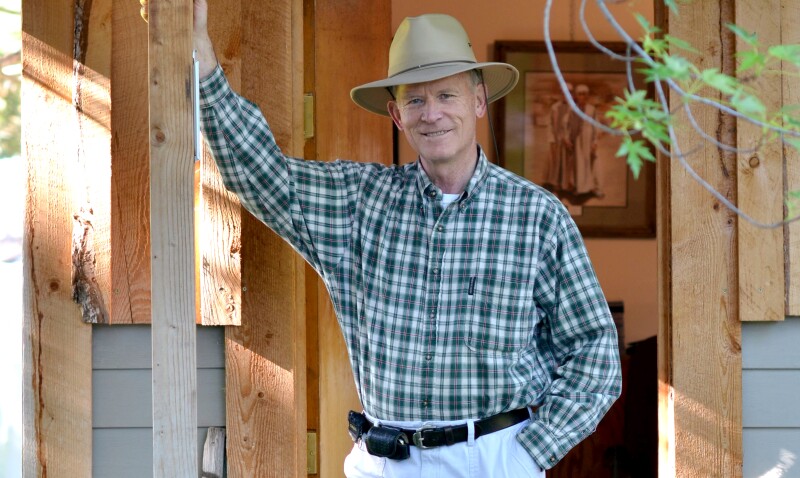

The art studio is as unassuming as they come: it’s an undersized square cottage framed by trees outside a home in Huntsville, Utah. With its size and trappings—a broom and an upturned wheelbarrow flank the small front window—you might mistake it for a common tool shed.

The artist laboring inside is JR Johansen, a man whose own exterior somehow belies an unexpectedly gentle core. Johansen’s graying flat-top haircut and tall, trim build hint at his past as a military man. But there’s no intimidation here; he’s soft spoken, with a mild manner that instantly conveys safety. This is a man on an exceptional mission: he’s creating portraits of missionaries who lost their lives during their service. And in the process he’s healing unseen wounds inflicted on families experiencing a particularly stinging loss, as well as wounds of his own.

Since his missionary portrait project began a handful of years ago, Johansen has produced scores of portraits of deceased elders and sisters. He reverently researches and renders each subject, then donates the portraits to their families. This is art with meaning much deeper than meets the eye. It brings comfort to grieving families, softening the blow of losing a loved one whose departure on a mission was meant to be a joyful—and temporary—season spent in the service of God.

And through the process, Johansen has found relief from his own physical and emotional scars, including those carried home from the Vietnam War. They’ve burdened Johansen for decades, but without those scars he may never have started painting at all.

War

As a young soldier in Vietnam, Johansen and his squad lived and fought in oppressive overgrown jungles. There among the trees, a rustled branch could signal the presence of either harmless orangutans or stealthy enemy soldiers. During one mission, Johansen’s squad unexpectedly felt moisture falling from the sky and dripping from the foliage high above. But this wasn’t rain; it was poisonous Agent Orange, a tactical herbicide dropped by aircraft onto the soldiers. “We were out where we couldn’t shower, couldn’t shave, couldn’t anything, so it was on us for a day or so,” Johansen recalls—long enough for the chemical to seep, unfelt, into his blood and organs. Over the following decades, the Agent Orange would slowly exact a toll from his body; a heart attack came in 2013, and later blood clots invaded his lungs.

War trauma gripped his psyche as well. Before the war, he’d faithfully served a mission and married in the temple, but returning from Vietnam, something felt different. “I wasn’t sure what to expect,” Johansen remembers. “I knew I had the support of my family. I was married with two children, and I believed they all loved me, but I wasn’t sure I loved myself. I hoped and I believed that God still loved me, but I wondered.”

Peace

On advice from a therapist, Johansen started painting to aid his psychological healing, even as his physical health continued to diminish.

“I always had a desire to be able to do good in some way with art,” says Johansen. “So … I came up with the idea of painting portraits of children and donating them to the parents. I initially began painting portraits of children who had terminal illnesses or who had passed away.”

At minimum, he figured the paintings were good practice, and it would be a bonus if a family liked their portrait—“and if they didn’t, they could throw it away,” he says. But nobody threw the paintings away. “As time went on, I could tell that the parents and families seemed to be very pleased,” he recalls.

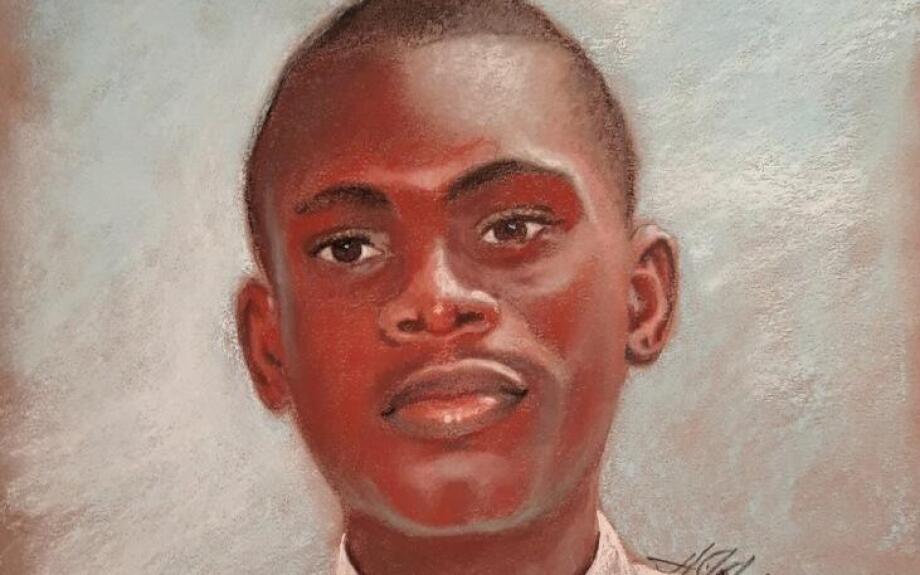

It didn’t take long before an unexpected request came: “I got a call from a mother who had lost her missionary son,” Johansen recalls. “She asked me if I painted missionaries.” Johansen agreed to paint a portrait of the late Elder Mason Bailey, a young man from Richfield, Utah, who had been struck by a car and killed while serving in the Stockholm Sweden Mission. Johansen figured it was a one-off project.

But after he displayed Elder Mason’s portrait in an art show in Salt Lake City, a woman approached Johansen with another request for a missionary portrait. The woman’s niece, Sister Vanessa Ann Bentley, was killed in 2011 in an automobile accident while serving in New York.

So despite his declining health, Johansen started on his second missionary portrait. “During that time my health took a dive,” he says. “I thought I was going to die. I didn’t even get the portrait finished, but I sent it to the family—as much as I had done.” Sister Bentley’s family was touched by the beautiful, albeit unfinished, portrait, which they framed and hung. Shortly thereafter Johansen was hospitalized, but mercifully his health improved, and then requests for missionary portraits “mushroomed,” he recalls.

The requests came from all over—from families whose loved ones had died recently and ones who had died decades before—and Johansen accepted every single one. He’ll create a portrait for any deceased missionary, “as far back as we can find a family member who wants a portrait. I did one from 1942—that’s the oldest one I’ve done. It went to [his] nephew,” he says.

Johansen’s fourth missionary portrait went to Greg and Cindy Thredgold, whose son Elder Connor Thredgold died in 2014 of carbon monoxide poisoning in Taiwan. To this day Greg avoids looking at photographs of his son. “He has a really hard emotional reaction to that,” Cindy says. “But this portrait that JR has done makes it way easier to just look at that portrait and feel Connor.”

Healing

Cindy Thredgold, who runs a website documenting all Latter-day Saint missionaries who died while serving, soon joined forces with Johansen to expand the project. The two of them starting actively seeking out families of deceased missionaries so Johansen can offer them a portrait at no cost. For recipients like John Jeppson, whose daughter Jazmyn died in 2016, Johansen’s painting represented “a form of healing, a way for [Jazmyn’s] legacy to live on,” says Jeppson.

As they work together, Thredgold has watched firsthand as Johansen’s difficult past slowly releases its grip on his mind and body. “He feels like this is keeping him alive,” she says. According to Johansen, “War is the opposite of peace. Painting and donating portraits bring me great peace.”

War is the opposite of peace. Painting and donating portraits bring me great peace.

To date, Johansen has completed over 120 portraits of deceased missionaries from across the globe—young elders and sisters and senior missionaries alike. And it’s not uncommon for him have spiritual experiences as he paints. “I don’t know how to explain it. There are just things that happen,” he says. “There’s almost like a divine connection that I have with them.”

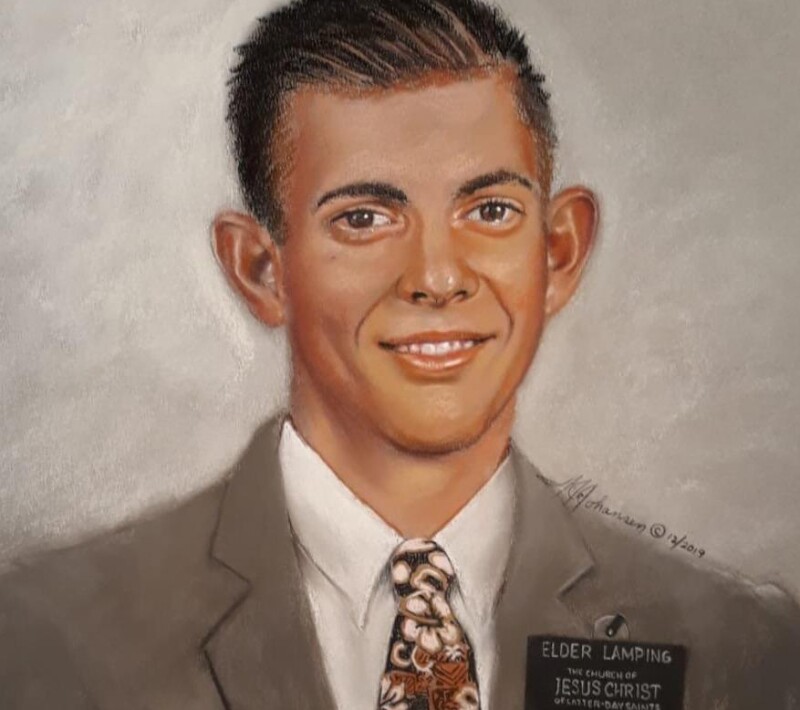

On one occasion, he put on a favorite Christmas album by David Archuleta and was soon lost in the brushstrokes of a painting of Elder Zane Lamping, a young missionary from Moapa, Nevada, who had suddenly collapsed and died at the South Africa MTC. As the refrain of “silent night, holy night” sounded in Johansen’s ears, he marveled at the beautiful voice he heard harmonizing with Archuleta. But then, Johansen recalls, “I stopped painting because I knew that David Archuleta did not have others singing harmony with him. So I played it back, and I didn’t hear the harmony.”

Sensing that something sacred had occurred, Johansen quickly texted Elder Lamping’s mother and asked, “Does Zane have any interest in music?” Zane’s mother phoned back. “She said that Zane sang in the ward choir, the school choir, and he enjoyed singing harmony,” Johansen recalls. “And that put it all together for me,” he continues, his voice thick with emotion.

Progress

Johansen knows what it’s like to answer a formal call to serve—he’s served five missions himself. As a young missionary in Denmark, he met his future wife, Deanna, and the two of them later served three missions to Nigeria. Later, Johansen served an additional nine-year stake mission locally. But now, missionary portraits have become his mission—and though unofficial, it’s just as important to him as any Church or military assignment.

What propels Johansen to keep accepting missionary requests, and even to seek out more families who’ve never heard of him? He’s found that “the peace and the emotion [the families] had and that I had is something I cannot replicate painting any other subject,” he says. “I am not able to do much physical activity because of my service-connected disability. But I can sit in my little studio and paint portraits day after day, and fully enjoy it.”

As the number of recipients has grown, the paintings have connected families of deceased missionaries, including through annual gatherings where stories are shared and celebrated. John Jeppson, father of Jazmyn, says that through those gatherings, “we have become close to many of the families that JR has done these portraits for, and we have helped each other through the loss. JR [has] been a huge part of bringing some of that healing to families like ours.” In addition, Johansen worked with Heather Burton, whose son Elder Joshua Burton died in Guatemala in 2013, to create a printed book containing all the portraits, accompanied by stories of each missionary. A copy was donated to each missionary’s family.

With help from the likes of LaMar Creamer, a longtime friend of Johansen’s, no grieving family is too far for Johansen to reach. Lamar and his wife Tami have made a handful of journeys to deliver portraits in person as far away as Australia and Chile. LaMar says that the few-second pause after unveiling a portrait for a family is ample payment for the time and expense. “The calm that comes over the faces of the people receiving it … that moment is so ‘Spirit-tingly’ that it’s worth everything it takes to make those deliveries.”

That moment is so ‘Spirit-tingly’ that it’s worth everything it takes to make those deliveries.

Back in Hunstsville, Johansen continues working quietly in his tiny studio. He’s painted children, fellow soldiers, and other subjects over the years, and he’ll likely do more of them. But above all, he’ll paint missionaries.

“There’s something about the experience I have while painting [missionaries] that’s unlike any other experience. … I didn’t start painting thinking I was going to become a great artist—and I’m still not—but there’s a connection I have with the missionary and with the Spirit that I believe guides me.”