Note: Jennifer Reeder was one of the compilers of the book, At The Pulpit, and some of the information in this article comes from that book. Another source used by Reeder in compiling this article was global histories resource on the Gospel Library app.

I have loved researching and writing about my ladies—Lucy Mack Smith, Emma Smith, Eliza R. Snow, Zina D. H. Young, and Emmeline B. Wells. I honor and respect their great works. But these women are just five of so many more. I invite you to learn about some whose names you may have never heard. They are worth it—you want these ladies on your team.

1. Jane Snyder Richards was the queen of the Weber County Relief Societies. She was born in upstate New York in 1823. She became acquainted with the Church when her brother and sister were converted, and the Snyder home became a meeting place for missionaries. One of those elders, Franklin D. Richards, caught her eye; they were married in December 1842 and moved to Nauvoo, where she joined the Relief Society in 1844.

The Richards family left Nauvoo in 1846, but even before reaching Winter Quarters, Franklin was called on a mission to Europe. Twenty days after he left, Jane delivered a baby boy, who only lived a few days. Her toddler daughter, Wealthy, became very ill, as did Jane. Wealthy soon died, and Jane grew more depressed. She later wrote, “My husband was to be away for two years and the hardships he might suffer made his return seem most uncertain. I only lived because I could not die.”

Jane did live. Franklin found her two years later, waiting for him in Winter Quarters, and together they traveled to the Salt Lake Valley. In 1867, Brigham Young assigned the Richards family to help settle Ogden, where Jane’s health continued to trouble her. Nevertheless, her bishop wanted to call her as Relief Society president. Jane took some time to think about it from her sickbed. Eliza R. Snow visited her and gave her a blessing, effectually healing her, and Jane was set apart as Relief Society president of her Ogden ward in 1872. She also led the first organization of young women in the city. In 1877, Brigham Young envisioned the idea of stake Relief Societies in each county as he reorganized stakes and wards before his death. Jane became the first stake Relief Society president, a position in which she served for over thirty-one years. Upon the death of general Relief Society President Eliza R. Snow in 1887, Jane became the First Counselor to the new President, Zina D. H. Young.

Jane Snyder Richards passed away on November 17, 1912. Annie Wells Cannon paid this tribute to Jane in her obituary, commenting on her life of service: “She knew no place to draw the line when there was a call for help. She surely lived with the spirit of Relief Society work ever in her heart.” Relief Society service saved her, and she lived for it.

2. Ellenor Georgina Jones gave a beautiful talk for the young women of the Salt Lake City 11th Ward in 1882 about prayer. Beyond that, there is not much known about her. Born in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1832, she was living in Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1850, according to census data. The census also tells us that she married Berry Jones and moved to San Mateo, California, by 1860. After Berry’s death in 1863, she married Hugh Jones in San Francisco in 1865, and the two later separated. She traveled back and forth between California and Utah from 1870 through the 1890s. A San Francisco city directory in 1873 listed her as a widow. She died, alone, in Redding, California, in 1922. There is no existing photograph of Ellenor.

More digging in the 1850 census shows that her mother was born in Kentucky, and the head of the household was a Black man from Virginia. Ellenor, her mother, and her brothers and sisters, who were born in Mississippi, Ohio, and Tennessee, were listed as mixed race. In Utah and California, however, there was no mention of Ellenor’s multiracial heritage, even at a time of Civil War–era racial unrest and the Church’s ban on priesthood ordination and temple admittance for Black people. Instead, Ellenor performed temple work, and her son was ordained to the priesthood.

Ellenor’s 1882 talk said more about Ellenor than anything else. Here is a tidbit: “My young friends, it is well for you to remember, while traveling on this journey of life, that there is no prison so dark, no pit so deep, no expanse so broad, that the Spirit of God cannot enter; and when all other privileges are denied us, we can pray, and God will hear us. No one can take this from us.”

We cannot lose Ellenor to merely a number in the census.

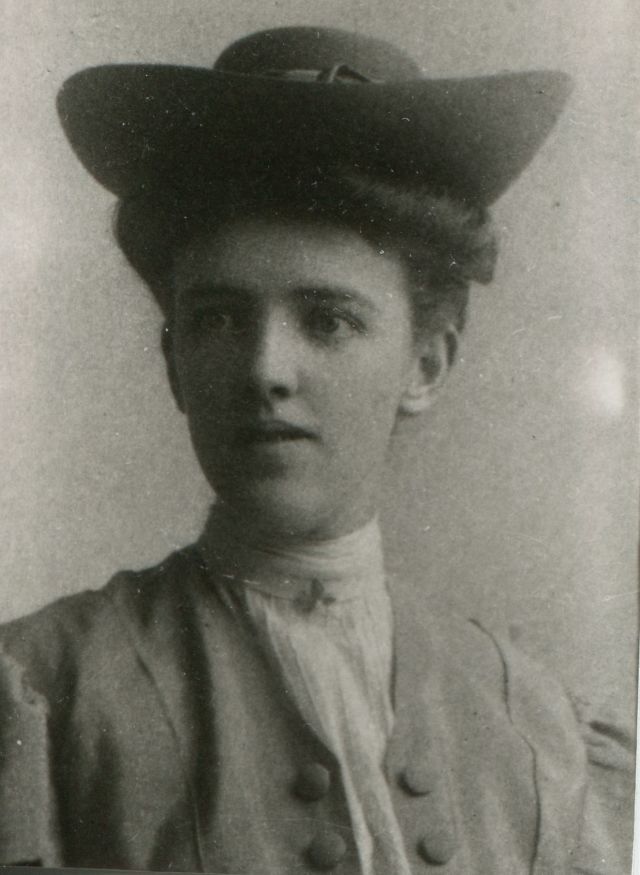

3. Rachel H. Leatham was the daughter of converts from Scotland and England. She was among the first generation of unmarried women to serve a proselytizing mission for the Church in 1906, assigned to Colorado. She worked in and around Denver, splitting her time between duties in the mission office and teaching people about the gospel. In a weekly report to her mission president, she wrote, “I have had a number of good gospel conversations and have been fortunate in getting into the homes of the people.” She was an ordinary sister missionary.

What happened next makes her extraordinary. Upon her return to Salt Lake City, Rachel volunteered as a guide on Temple Square. In 1908, she became just the third woman ever included in a conference report when she spoke at an overflow session of general conference. Here is part of her talk:

“I am one of the happiest girls in all the world, and it is the gospel that makes me feel this way, for I do know that the gospel is true. I do know that God our Father, and his Son, Jesus Christ, came down and brought the gospel and established it and spoke to the Prophet Joseph Smith.” She continued, “I want to say again that I know the gospel is true. Not because my father knows it, not because my mother has always taught it to me, but I know that the gospel is true because God has revealed it unto me. His Spirit has borne witness unto my spirit, and that testimony is God’s most precious gift to me.”

Extraordinary, I tell you.

4. Speaking of sister missionaries, have you heard of Olga Kovářová Campora? She may not have served a proselytizing mission, but she had her own way of teaching fellow Czechoslovakians about the Church through yoga.

Olga was a doctoral student at Masaryk University in Brno in the 1980s, a time when communism prohibited the practice and proselytization of religion. She became interested in yoga and met Otakar Vojkůvka, the last person to be baptized in the Czechoslovak mission in 1939 before the start of World War II. He began teaching “Christian yoga” classes in his home, where he blended traditional yoga techniques with Latter-day Saint scripture and principles. Over several months, Otakar gave Olga several books about the Church to read and discuss, including a nearly 40-year-old copy of the Book of Mormon in Czech. Late one night as she read, a joy she had never known entered her heart. A powerful conviction came to her with perfect clarity. “God lives!” she whispered aloud. “I listened to my own words and felt the reality of God in my life as his love filled my whole being.”

► You may also like: How Members of the Church Behind the Iron Curtain Shared the Gospel Through Yoga

Olga was baptized in the summer of 1983 in a nearby reservoir after dark. Shortly after her baptism, she became a missionary by teaching Christian yoga classes of her own. She started a summer camp, and through her lectures, 130 people embraced the gospel and were baptized. Olga said, “I had become one new link in the chain of women who have been significant among Latter-day Saints in Czechoslovakia.” I’d say Olga, who is still living, has played a significant role in the Church’s history.

5. Last, but not least, let’s look at Julia Mavimbella in Soweto, South Africa. She was born in 1917, and her father passed away when she was five. Her mother was left to raise the children on her own, finding work as a washerwoman and a domestic worker. Julia became a teacher and a school principal, then married her husband, John, in 1946. Together they built a home and a family. John was killed in a car accident in 1955. The police blamed him for causing the collision because he was Black. Julia became bitter and described feeling a lump of hatred.

In the mid-1970s, peaceful apartheid protests turned to violent outbursts in Soweto, and the public schools were closed. Julia decided to teach local children how to garden. She established a community garden that symbolized hope to people who only knew fear and anger, and she used seed packets to teach children how to read and how to be responsible. Through acts of reclamation and gardening came lessons of social healing. Julia said, “Let us dig the soil of bitterness, throw in a seed, show love, and see what fruits will grow. Love will not come without forgiving others. Where there was a blood stain, a beautiful flower must grow.”

Julia was among the early Black converts in South Africa in 1981. She served as Relief Society president of the Soweto Branch and as an ordinance worker in the Johannesburg temple. Don’t be bitter; be better.