Stories in this episode: Jim feels conflicted about receiving a life-saving kidney until three words change his perspective; A surprise friendship leads Arthur to see the connection we have with others is far more precious than material possessions.

Show Notes:

This episode is sponsored by TOFW.

Find Elder Dieter F. Uchtdorf's talk "Grateful in Any Circumstances" here.

Quote: "In any circumstance, our sense of gratitude is nourished by the many and sacred truths we do know: that our Father has given His children the great plan of happiness; that through the Atonement of His Son, Jesus Christ, we can live forever with our loved ones . . . "

—Elder Uchtdorf

Quote: "You do not need to see the Savior, as the Apostles did, to experience the same transformation. Your testimony of Christ, born of the Holy Ghost, can help you look past the disappointing endings in mortality and see the bright future that the Redeemer of the world has prepared."

—Elder Uchtdorf

KaRyn Lay:

Hey friends, I wanted to take a quick minute to say thank you. Thank you for sending us your stories on the pitch line. thanks for sharing the stories with your friends and your family and thank you for finding us on Instagram and Facebook. I know social media is a mixed bag and sometimes you really need to disconnect for a few minutes, or for a few days, or for a few weeks just to get your bearings. But social media also gives us the unique opportunity to have conversations about these stories that we're hearing together and we love talking with you. We love hearing what you loved about the episodes and how they've affected you. And we love the opportunity to talk back. So if you're on Instagram or Facebook, you can find us @thisisthegospel_podcast. We promise it'll add good things to your day. Now, let's get on with the stories.

Welcome to This Is the Gospel, an LDS Living podcast where we feature real stories from real people who are practicing and living their faith every day. I'm your host KaRyn Lay. Annyeonghaseyo! Okay, I know that sounded like I knew Korean really, really well. But I don't really speak any other language besides English. I tried to learn Spanish in high school and American Sign Language in college and I really tried to learn Korean when I lived in South Korea for two years working. But unfortunately, and despite my best efforts, it turns out, I'm pretty useless as a second language learner. Besides being able to communicate the kind of food that I want, which is very important, and where I'd like the taxi to turn, the only real words that I got down in all those years of praying for the gift of tongues, were Hello, "annyeong." And of course, thank you, "Gracias," "Dangsinboda." I think it's interesting that whether we're a toddler or 30-year-old, or it's our first language or 21st, words of gratitude are some of the very first that we learn. Offering gratitude and communicating gratitude are such a huge part of both our social life and our spiritual life. But "thank you" is only one part of the gratitude equation and today, what happens after "thank you" is the focus of the two stories that we have for this episode. Our first story comes from Jim, whose unique experience with gratitude helped give him a glimpse into what it might feel like when he comes face to face with his Savior. We recorded Jim's story remotely from his home in Pennsylvania, so you might notice a slight difference in the recording quality. Here's Jim

Jim (2:26)

It had been a late night as I was contacted by my mother and was told that she had been diagnosed with polycystic kidney disease. We talked about the fact that she might have to get dialysis for the rest of her life if she didn't get a transplant. We discussed the rigmarole around a transplant, and she was down and I could tell that she was struggling with it. My heart ached, worrying about what would happen to her. She did dialysis for about three or four years. Waiting for a kidney was a time of much anxiousness as a family. All of my siblings and I were tested, and none of us was a match. So not only were we not a match, but two of the four of us kids were diagnosed with the same disease. I was one of the two that were diagnosed. I remember being disappointed, but not really upset at first. I was still young and felt nothing would affect my health. I was healthy, I pretty much did anything I wanted. She finally received a kidney between 2000-2001 sometime.

As the months and years ticked by, my anxiousness grew, and I feared that I'd suffer a similar fate as my mother. I followed up with a kidney physician in my town, we kept track of my blood pressure and my kidney function. I was eventually put on a donor list, which, you know, most of the time it takes a very long time to receive a kidney. Eventually, the doctors and I felt like a preemptive transplant would be the best situation for me—being as young as I was—from a live donor. So we decided to look up the two siblings that I had that did not have the disease to see if they were a match. My sister Christine was a perfect match, and she gladly agreed to donate one of her kidneys. Now, this was a time that, unfortunately, I have to confess that I was not living the Gospel life I should have. It had been years since I had really connected or reconnected with my church roots. I'd served an honorable mission but had not held on to what I knew to be true when I returned home. Why that was? I don't know why, but it happened. And I subsequently was at a time in my life that things were not the best with regard to my spiritual growth and development and actual participation in church. But after my sister was deemed a match, and committed to give me a kidney, my life and the way I was living became an issue. When I say it was an issue, I didn't change a whole lot in my behavior, but I was overcome with a sense of guilt and spiritual loathing. I didn't feel worthy or deserving of what my sister was willing to do. It takes great sacrifice to donate an organ. Things can go wrong during surgery, pre or post-surgery. It's not like getting a tooth pulled, it's a serious surgery and major veins and arteries are involved. I decided since I lived relatively close to Palmyra, New York, that I'd go and maybe spend some time in the grove.

I was searching for comfort from the Lord. I guess I thought perhaps that that was a good place to search for it. My wife is a nonmember of the church but is a strong Christian woman. I worried that she would wonder, you know, what the heck is going on with my husband? And I explained how I was feeling and that I wanted to go spend some time in the grove. She was more than supportive. I should also say that, although she was not interested in the church per se, with regard to converting or investigating the Church, she continuously hammered me about going to church and living the way I was brought up to live. So she also understood very well, what the grove meant and what had taken place there and why I wanted to spend some time there. It was a beautiful day in upstate New York that day. I remember some of it, but what stood out to me the most was the quiet that existed in the grove. I was alone there that day. There were no visitors or people walking around taking pictures. It was kind of the offseason. I was thankful that I could be alone. I remember how quiet it was and it had a great calming effect on me. I believe I was comforted. I don't believe I had a burning of the bosom or an earth-shattering experience in the grove, but it was quiet and reverent. And although I was comforted, I also felt that I needed to change some things in my life. I eventually resolved my guilt, to an extent, and allowed the surgery to take place.

So the surgery was set for September 2007. I had the surgery down at the University of Pittsburgh medical center's Montefiore Hospital. My sister and her husband had flown in from Utah—that's where they still lived—to prepare for the surgery. The procedure on the day of surgery is quite unique. Typically, they take the donor down to pre-op, roughly a half-hour before the patient that's set to be the recipient of the organ. When they took me down, the place was a madhouse. There were people everywhere. There was a nurse that was barking out orders sending some people one way, and other people the other and it seemed like she was at this big desk. And it reminded me of a judge sitting there handing out sentences as people were wheeled in. When they wheeled me into my slot that they had there, I look to my right and lying on the gurney next to me was my sister Christine. She was in the process of answering questions probably for the 20th time. And meanwhile, I had an anesthesiologist asking me the same questions for the 20th time. Suddenly it seemed as though, while all this was going on, Chris and I were kind of just aware of each other. I finally looked over at her and said, "Hey."

She said, "What?"

I said, "I want you to know how much I love you."

And she said, "I love you, too."

I, again, said, "Hey," a few minutes later, and she again said, "What?"

I said, "Are you scared?"

And she said, "No, are you?"

I said, "No." We had both received Priesthood blessings and I was confident in the power of those blessings. Shortly thereafter, they started to wheel her away to surgery. And I once again said, "Hey."

And she said, "What?"

I think I remember her being somewhat annoyed. And I said, "Thank you."

She looked back at me and said, "You are welcome." This was a moment in time between my sister and I, that was full of love and sacrifice. It was an example to me from what true sacrifice is and what Christlike love looked like.

In the years since, thankfully, I've straightened myself out spiritually. I've never resolved in my mind, however, or my heart, the willing gift of my sister. It was an unselfish gift that I am forever grateful. And we have a bond that will live on as long as I live. As I study these days, particularly when studying about the Atonement of Christ, I often think of that exchange between my sister and I, in that pre-op room. I'm doing everything I can to prepare myself spiritually, live the gospel as best I can, and do the things that I know I should be doing. My hope is that someday when I stand before the Savior, I can apologize for the suffering my sins caused him. I hope to say "thank you" and I ultimately hope to hear, "You are welcome."

KaRyn Lay (13:11)

That was Jim. You probably caught the part of Jim's story where his desire to be a grateful recipient of his sister's kidney drew him towards the Savior. I think it's such a beautiful reminder that if we let them, the difficult things in our lives can lead us closer to Jesus Christ as we seek to be filled with gratitude. And I have to say, I am filled with more motivation to repent and get right with God as I consider Jim's vision of his reunion with our older brother. Our next story from Arthur illustrates how true charity can be found in the ways that we welcome one another into our lives. Here's Arthur.

Arthur (13:47)

Like a lot of young 20 somethings, I was idealistic, and I felt like I need to go make my mark on the world and I'm going to go to Africa. I'm going to do aid work and I'm going to help people. Totally naive.

When I had finished my degree at Brigham Young University, I had spent four years there, I was the captain of the men's soccer team. I loved, loved my time at BYU and playing for the soccer team and I knew I wasn't quite ready to be an adult yet. So I was kind of looking for an adventure. And the Olympics had come to Salt Lake City and an organization called, "Right to Play" that was started by Johann Olav Koss, a gold medal-winning speed skater from Norway came. And I kind of got excited about their work and what they were doing and the way I could maybe bring my soccer knowledge and experience to the refugees in war-torn Uganda. And so I interviewed and became a volunteer for "Right To Play." There was a moment when I was leaving U.S. soil on the airplane and flying over the Atlantic when I thought, "What have I gotten myself into?" And you fly over the Sahara, and you fly over all the desert of the Sudan, I think even as we were coming in, and it's very surreal, and it doesn't feel like anything you're comfortable or familiar with. I mean, I was very much out of my comfort zone for the first little bit. We were flying into a little tiny village called Arua, Uganda, which was the hometown of the Ugandan president, Idi Amin, who had just absolutely decimated certain tribes within Uganda, massive genocide taking place before that. Still a lot of scars. And you have, you know, as an American, as a white kid from Utah, you have a little bit of a sense for the legacy of not just Idi Amin and the Ugandan history, but the history of colonialism, the history of, you know, European and white colonizers in that part of the world. But, I mean, I was clueless. I was completely, completely clueless. And so here we were sort of, you know, there's a group of about six or eight of us who are coming in working with the UNHCR, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, and tasked with the job of implementing sports programs for kids in these refugee camps. And the refugee camps were about an hour and a half drive on terrible dirt roads outside of Arua. You're working with refugees that are coming across the border from the Congo, and from the Sudan, from those civil wars, from those conflicts. And refugee life is a completely different equation than even this little bush town of Arua, where you can still get meals and there are little hotels and televisions to watch, you know, football matches on and some of the amenities. But you go into those camps, there is just nothing. Some people are new arrivals who are just sitting there with a pot to go to the bathroom and that's it. They're exposed to the elements, they don't know where they're going to get their next meal, they've traveled from these distances to just escape the violence of those conflicts. You're looking at real poverty, real desperation, real need, and you're supposed to have answers and you're supposed to have solutions. And the truth is, we really didn't.

And here are these kids from America or Canada, or some from Europe, who are saying, "Hey, let's play sports together! Let's run soccer clinics." Who was I to sort of say, this is going to help children feel better, you know, psychologically, physically, this is going to help them overcome the trauma of war. Like, are you kidding me? Really? I mean, it's such a ridiculous notion that we would have anything to offer. But we're there and so you have to sort of pretend like you do have something to offer. I mean, I wanted to help people. I felt like I had benefited so much in my life from playing soccer. From that sport from the teamwork and the camaraderie and it was just something to, I mean, you're in the moment, right? And if giving these kids a moment to play football, so they could forget about the world they were coming from, they could forget about the poverty, they could forget about the violence, I wanted that to happen. That was my reason for going. But there was a part of me too if I'm honest, that was, you know, I wanted people back home, they were saying, "Oh, you're so brave. You're so altruistic. You're such a good person," right? And that sort of feeds your ego and then you get there and you realize you have no answers and there's so much hubris. I asked myself every day I was there, whether or not we should even be there. It was that complicated. Which is why, and I'll get to the point of the story when we met Ayub and interviewed him to be our driver—we had to buy a vehicle and have some way to transport ourselves back and forth between the village of Arua where we'd get supplies. And then we'd go out to the refugee camps and stay for a week or two at a time sometimes because it was just hard to go back and forth. And we were trying to service two different refugee camps with populations of over 50,000 people in each of those camps: Rhino camp, and Invepi camp. And so we go through all of these interviews with these different drivers, potential drivers, right? And they're desperate for money, they're desperate for a job. And you see the tangible dependence that they have on our being there, even though we don't have real solutions to these long, systemic problems that are occurring in the refugee camps, right? Displacement, war, poverty, violence, illness, like we haven't, we have no answers, but we've got to find a driver to get us over. That's our only task. And so their motivations and our motivations sort of gets complicated too, which is when Ayub walks in. And he's missing a tooth, and he's laid back and it was almost like he couldn't care if he got the job or not. And we take him up this like big, rocky mountain thing to see how his driving skills are. And we and we do things like put in American rock music to just see how he'll handle it. And he just rolls down the window, puts one arm out, drives with one hand on the wheel, completely laid back. And then while he's driving tells us the story of how he missed his tooth, how his big front tooth was missing. Because on another caravan on another job for another NGO, the truck had rolled, and it rolled into a river, and he dove in to try and save somebody and busted his tooth on a rock. And we're like, that's our guy. We're hiring him. He's amazing.

I started to sort of develop a friendship with Ayub and became very, very close with him, closer than some of my other colleagues even. I was so close to him he invited me into his home. And Ayub was Muslim and he was the first Muslim that I knew well and I knew personally, it was my first experience with that religion. And so I was in Uganda long enough that as Ayub and I started to become friends, it happened to be the holy month of Islam coming up, or Ramadan, when they fast from sunup to sundown. And it's a time of sort of Thanksgiving, but also special focus, religious focus, but it was a sort of a poignant, intense spiritual time. And we knew Ayub was going to be participating in Ramadan, he was going to be fasting. That meant while we were out at the refugee camps, and we were eating, he was not going to be eating. There's already not a lot of resources, it's hard to get food. You know, we're buying chickens on the side of the road and we're, you know, having people in the refugee camp slaughter goats for us, and it's a big deal to eat and he was going to be foregoing that. So it became really meaningful to me and deepened our friendship when he was willing to share that religious experience with me. And we were traveling back and forth between the camps and its long, dusty, terrible road. Sometimes if it was in the rainy season, there's mud and cars are sliding off the road. And as soon as the sun would go down during Ramadan, he would pull over and walk into a stranger's hut who had prepared a meal for anybody who happened to be traveling through or traveling by. And he would always include me and bring me into that intimate, sort of brotherhood of Islam that was especially poignant during Ramadan. But it occurred to me when we were— not just during Ramadan, but all throughout my time in Uganda, I had nothing in common with Ayub. I mean, really, nothing in common. And so one day when he said—we were driving back from one of these Ramadan meals, you know, he just turned to me and, and said, "Tomas," they called me Thomas, not Arthur. They couldn't pronounce my name very well. He said, "Tomas when we breathe, we breathe in the name of God."

And I thought that's the only thing we have in common. It's just the air we breathe. We don't have the same religion, we don't have the same socio-economic, we're from different continents. And it was so meaningful to me. I was so grateful that my young, naive idealism could be manifested in a tangible, practical way through this man. That all the things I believed about the commonality of humanity was real and it was true, it wasn't just a good idea. And it manifested itself through Ayub. When the only thing we had in common was the air we breathe, but it came from God, we had the same maker, we had the same Heavenly Father.

He used to like to put his finger up to my finger and push really hard, our index fingers would touch and he would say, "Tomas, you are my brother." And make sure we made contact like that. For me, that was important, that two people, we could transcend race, we could transcend religion, we could transcend a history of colonialism and violence. We could transcend all that stuff and we really could be unified. We could really be brothers. I didn't feel like I was an imposter or I was a wannabe white savior figure, I felt like I was Ayub's friend. So when I had to break a rule of my NGO to take the vehicle to drive him to another village close to the Congolese border for his mother's funeral, I didn't think twice about it. I did it because Ayub was my friend and he didn't see me as just a means to an end. He didn't see me as money or a resource. It was a friend helping his friend get to his mother's funeral in a faraway village. And that relationship, I think, carried me through my six months there and we're not in contact now. And you know, I have no idea what's happened to him. But because of that closeness and that recognition that I was more than just a foreigner who was coming in with ideas about how to save the world and fix things, I mean, how ridiculous is that. But he allowed me to just be me and to see me for who I was to and not just an interloper who's caused a lot of problems in that part of the world for him and his people. But as a true brother. He should not have seen me as a brother, but he did.

What Ayub taught me is to be grateful for connection more than for things. I mean, the things are easy to see and to and to assess, and to make a judgment on. But the harder thing is to find a way to connect with somebody that cuts through all of that stuff, all of the labels and all of the layers of identity that we carry around with us based on our religion, our skin color, our gender, all of those things. They end up just stacking up so many walls and obstacles to getting to the heart of connecting with somebody. And so when you can find someone you can cut through all of that nonsense with and see them for who they really are, that's when I feel welcome. That's when I think what gratitude means and what feeling welcome means and when real charity can live. I always come back to that line he said to me during Ramadan, "Tomas, when I breathe, I breathe in the name of God." And every breath is a gift.

KaRyn Lay (27:16)

That was Arthur. When we breathe in, we breathe in the name of God. There is so much that can divide us in this world right now. And when we think about what connects us, what really connects us, like Arthur and Ayub, the breath, the air that we breathe, that is filled with God, well then we are filled with gratitude for all the things. And I think it actually makes saying, "you are welcome" that much easier. This interplay of gratitude and charity is such an interesting concept for me and one that I honestly had never really thought of until I listened to these stories. I started to think about the words "You're welcome." There's something in the way that Jim envisioned the savior offering His Atonement so freely and with such love I mean, at this point in my social development, saying "you're welcome" in response to someone's expression of gratitude is really nothing more than an idiom or reaction like saying, "bless you" after someone sneezes or "sorry," when you accidentally walk into a wall, or at least that's what I do. It's rote, it's automatic. And while it means something, it doesn't really mean all that it could.

But, what if like Jim's sister Chris, we really could dig into "your welcome" and mean it with all the possible depth inherent in the phrase. You know, in Spanish when someone says "Gracias," you reply with "De nada," which is loosely translated to mean, "it was nothing." In Korean, when someone says "gomabseubnida," you reply with "cheonman-eyo," which is a polite way of saying "No, no don't thank me." But in English, and a few other languages, we get to say "you are welcome." Think about that. It's really actually an amazing thing to say to another human being, an acknowledgment of our agency and intent to offer ourselves and our service with the truest charity, the pure love of Christ. You are welcome to what I've just given you. You're welcome. What might change in me if I started to say that with some intent? Now listen, I don't want to get all creepy about it. Like I'm not going to start staring deeply into stranger's eyes when I open a door for them at the grocery store and pronouncing "you're welcome," as if it was a blessing upon generations of their family. But maybe I could start to do things that I do for others with the kind of charity, the pure love freely given, that when you say "thank you," and I say, "You're welcome," even in a perfunctory way, I really mean it. No resentment, no obligation. You are welcome. And maybe the key to gaining that kind of welcoming heart is to start with our own "Thank you's." Elder Uchtdorf suggested that as we develop a sense of gratitude for all that we've been given, and gratitude for the things that we have in common because of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ, we can't help but be filled with charity towards others. In his April 2014 general conference address, "Grateful In Any Circumstances" he said, "In any circumstance, our sense of gratitude is nourished by the many and sacred truths we do know. That our Father has given his children the great plan of happiness, that through the Atonement of His Son, Jesus Christ, we can live forever with our loved ones. It must have been this kind of testimony that transformed the Savior's apostles from fearful, doubting men, into fearless, joyful emissaries of the master. When the apostles recognized the risen Christ, when they experienced the glorious resurrection of their beloved Savior, they became different men. Nothing could keep them from fulfilling their mission. They accepted with courage and determination, the torture, humiliation and even death that would come to them because of their testimony. They were not deterred from praising and serving their Lord. They changed the lives of people everywhere. They changed the world." That testimony of the Savior and His Atonement filled the apostles with gratitude and that gratitude fueled their gift to the world as they taught and offered themselves to the disciples of Christ. They were filled to the brim with "You are welcome." Just as Arthur and Ayub's friendship was filled to the brim with "You are welcome," and Jim and Chris's exchange of a kidney was filled to the brim with "You are welcome." This is possible, I believe because first, they understood that when they breathe in, they breathe in the name of God. And as Arthur said, "Every breath is a gift." Elder Uchtdorf continued with this, "You do not need to see the Savior as the apostles did to experience the same transformation. Your testimony of Christ born of the Holy Ghost can help you see the bright future that the Redeemer of the world has prepared." I hope this week as we seek to have a little bit more gratitude for the sacrifice of our Savior and its power in our own lives, that will, in turn, put just a little more meaning behind every one of our "your welcome's" as we strive to become more like Him.

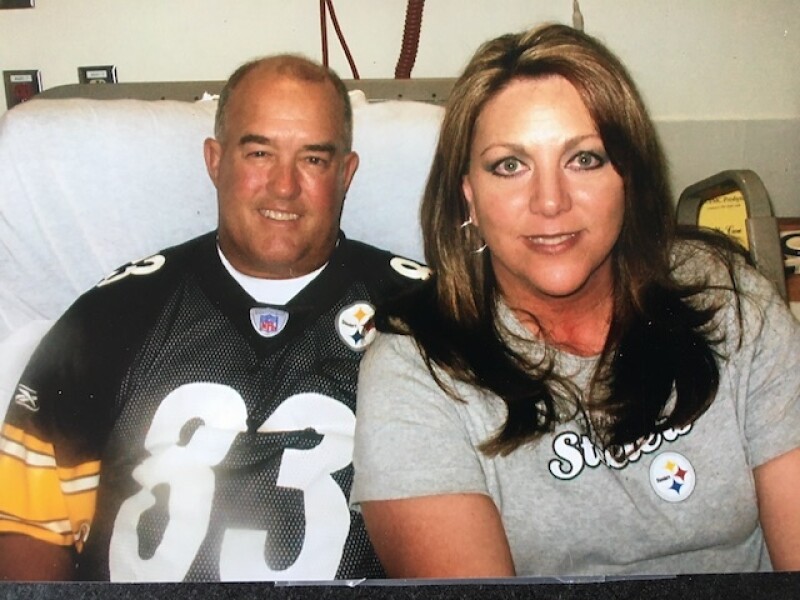

That's it for this episode of "This Is the Gospel." Thanks for joining us today. And thank you to Jim and Arthur for welcoming us into their stories and their faith. We'll have the transcripts of this episode along with some pictures and a link to Elder Uchtdorf's talk in our show notes at LDSliving.com/thisisthegospel. All of our stories on this podcast are true and accurate as affirmed by our storytellers. If you have a great story about your experience living the Gospel of Jesus Christ, we want to hear from you on our pitch line. Leave us a short three-minute story pitch at 515-519-6179. You can find out what themes we're working on right now and what we need for the pitch line by following us on Instagram and Facebook @thisisthegospel_podcast. If you love the stories that we've shared, please leave us a review on the Apple Podcast app or on the Bookshelf PLUS+ app from Deseret Book. We love to hear your thoughts about certain episodes, and every single review helps more people to find this podcast.

This episode was produced by me, KaRyn Lay, with story producing and editing by Katie Lambert. It was scored, mixed and mastered by "Mix At Six Studios," our executive producers Erin Hallstrom. You can find past episodes of this podcast and other LDS Living podcasts at LDSliving.com/podcasts. Annyeong!