Stories in this episode: A journey to learn more about his grandparents leads Jeff across the world to old chapels, monasteries and hidden towns only to find dead ends––until a chance encounter on a remote mountain side; KC’s inherited pocket watch had long since become a plaything for his kids, until a close inspection of the watch yields an inscription that broadens his definition of “family.”

Show Notes

KC and his brothers with Harriet when they were young. They lived across the street from her while they were growing up, she was always like family to them.

Sarah Blake 0:03

Welcome to This Is the Gospel, an LDS Living podcast where we feature real stories from real people who are practicing and living their faith every day. I'm Sarah Blake hosting today in place of KaRyn Lay. I'm happy to report that KaRyn is on the mend after a rough week recovering from COVID-19.

Our theme today is "Family Ties." But before I get into that, I want to talk about rock climbing. I am not a cool rock climber, but I have seen some movies. So I happen to know that most of the time rock climbers are clipped in to a whole coordinated system of ropes that are connected to secure anchor points. And then the other end of the rope is held and watched over by other climbers.

But there is also this insanely dangerous thing called free soloing where you climb without any ropes. You may have seen or heard about the documentary about climber Alex Honnold's record-breaking, totally legendary, free solo ascent of the El Capitan cliff face in Yosemite National Park in 2017. My husband and I watched that movie at an IMAX movie theater so the screen was several stories tall and the heights were dizzying.

I was clutching the edge of my seat and my heart was pounding like I was actually attempting the climb myself. And I felt like I lost about a pound in just hand sweat despite the fact that I already knew how it ended with Alex Honnold surviving the climb. And again, and again, I found myself kind of absent mindedly reaching down to find a seat belt in my movie theater chair, just so you know, I couldn't fall off El Capitan.

So this brings us back to the concept of family ties. Family ties is a phrase that we use in English to describe the connections that bind us to our families. For some people, these connections are biological. For some people, when they hear the phrase family ties, they think about the obligations and duties that we owe to each other. For some people, these ties have a lot to do with your shared family culture and expectations about how you live and make choices. And hopefully, for most of us, these family ties are also just about plain love and enjoyment of one another.

But I want to say that these family ties, whatever they look like, are part of the coordinated system of ropes that we need while we climb through life. In our spiritual and emotional lives, we all deeply deeply crave to be clipped into reliable ropes with somebody we trust on the other end. And I think that feeling that I had, as I reached for the imaginary seatbelt in the movie theater, I think that's how we feel if we imagine a life without any of those family ties or connections to other people. It makes your emotional palms sweat. Think of climbing through life ropeless, just one slippery handhold away from falling through space.

To know where we fit in a web of other people, and how we are tied into the past and connected in the present, and how our connections might last into the future, I think that's a very basic human need and it's part of our eternal and our spiritual DNA. And this week, we have two storytellers exploring these ideas with tales of family ties, and the lengths that we go to find them and the ways that they find us. First, we will hear from Jeff.

Jeff 3:23

I think, I think this story really begins with my curiosity about my grandfather because we were so close growing up. He actually wanted me to be a professional golfer so he put a golf club in my hands at age two. But that gave us a lot of time on the golf course and in a golf cart talking and, and sharing stories and things like that. However, he would never tell me where he was from or about his childhood or about his parents or anything like that.

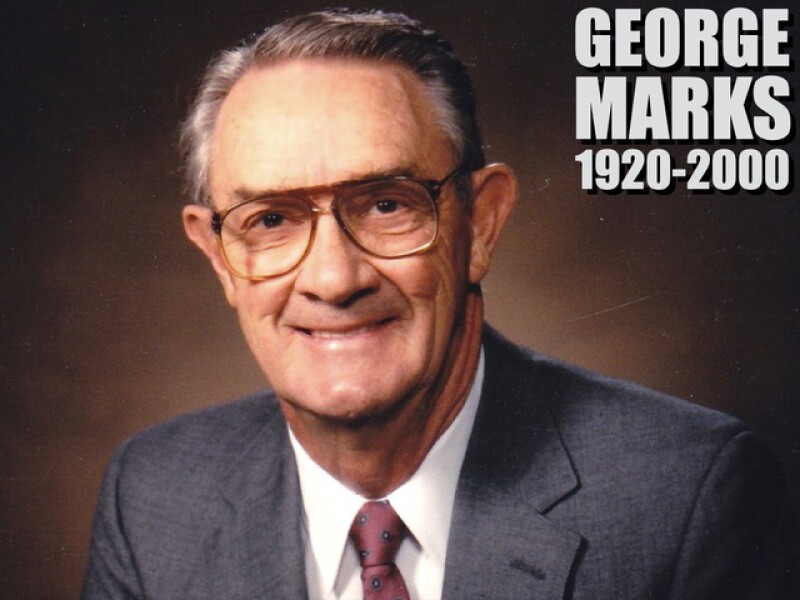

Both he and my grandmother would refuse to give me any more information than three points. And that was number one: He was born in the former Yugoslavia. Number two: he was raised in Worland, Wyoming. And number three: he changed his name from Mijušković to Marks. I didn't know anything about his family. I didn't know where he was from. I didn't know what his childhood was like. And if I ever asked any questions, he would always put his fingers to his lips and tell me to shish.

My dad, he never even knew anything about his parents. And if I ever asked him about it, he didn't know any more than those three things either. And both of his siblings have since passed away. So I don't have any other way of knowing anything about my grandparents. And it kind of made me sad when he did pass away in 2000 that I just didn't know enough about him because of how special he was to me.

Well, in my career, I've spent many years as a pediatric dentist as a remote EMT, spending time in humanitarian clinics all around the world. So I'm used to traveling into remote areas and kind of booking crazy flights and going from place to place.

Well 10 years ago, right after the Haiti earthquake, I got called to serve as a volunteer as a first responder there to help with the devastation from that tragedy. And on the flight, there was a gentleman sitting next to me, another volunteer, we were all in scrubs. And he was wearing scrubs with a University of Wyoming logo on them. And I turned over to him and just out of curiosity, I just asked him about his scrubs. And he said that he was a Wyoming fan because he came from a small town in Wyoming that I would have never heard of. And when I asked him about what that town's name was, he said that it was Worland, Wyoming, of all the places and I said, "That is crazy because my grandfather was raised in Worland, Wyoming."

He said, he asked me a little bit more about me and where I'm from and also about my name. And he said, "Tell me your last name again?" And when I told him it was Marks, he said, "You wouldn't happen to be related to the Mijušković, are you?" Out of all the things. that most random thing. And I just was completely blown away and he even told me on this trip, that if we make it through this trip, it was kind of a it was kind of a crazy humanitarian aid adventure he, he said, "If we make it through this, I want to meet back in Wyoming so I can show you all about your family show you everything about your family."

And so we went back there and he took us straight to the cemetery and I saw Mijušković gravestone. I saw the two gravestones of my great-grandparents. So these are the parents of my grandpa George. So my great-grandfather, Joseph, who died in 1951. And my great-grandmother, Meliva, who died in 1983. And this I was fairly emotional about this because, again, not knowing anything about my family, seeing the gravestones where my, my ancestors were buried was very special to me. And I had never done anything with family history work, genealogy, anything, my entire life.

This sparked kind of this spirit inside me not only of curiosity, but of really, something deeper. Something kind of more organic of who I am and where I come from. And finding my own identity through my grandfather was was kind of a fun adventure.

At this point, I came home and spoke to our family history consultant to have her direct me to a 1920 census. And I saw my great-grandfather's name on there, my great-grandfather Joe and his family on this census coming from the former Yugoslavia in a country called Montenegro. So, again, now I have dates. I have names of family members, I even have a country in the former Yugoslavia, which is again, nothing that I ever had before.

I was then told that if I was going to find out any more information, she even tried to do some research for me and couldn't find anything else, but I was going to really need a death certificate for my great-grandpa Joe. So I sent a fax over to the Department of Vital Statistics in the state of Wyoming to try to request my great-grandfather's death certificate. And after sending that fax at work, I went and saw a patient that day. And that patient's name, the mom's name, I see kids. And so like the mom's name was Maria, Danlavich. And that of curiosity, and this is literally five minutes after I sent this fax, I went to her and said, "You know, I've seen your kids for years and I've never even put two-and-two together. But I've been doing this family history work and I just sent this fax, and your last name looks an awful lot like my grandfather's last name. And I just wondered what country you're from your family's from?"

And she said that she's from the former Yugoslavia in a country called Montenegro. She told me she said, "If you ever wanted any help, you know I'm more than happy to help you with anything but you might want to start with some emails or some letters to the government, if you want to try to find out anything about your family since you're kind of at a dead end here with that trip to Wyoming." And, and since she spoke Montenegrin, which is like a dialect of Serbian, she offered to translate a letter for me saying, you know, "These are my great grandparents, this is my grandfather I'm trying to find any information I can about my family, this is their information, their birth dates, their death dates, where they're buried, is there any information you can provide for me?"

And months went by and I never heard anything. So I got on my phone or even on my computer and started doing a little bit of research on how – what it would take to get from Seattle to Montenegro. Just for kicks, if I were to take that letter that she translated for me, go to Montenegro, and even if I had to go door to door to try to find anything more about my family, again, the spirit was burning inside of me to really find out more and it just wasn't enough. I wasn't satisfied with my trip to Wyoming and with this other stuff.

And there had to have been something that I can maybe relate to or connect with, on a deeper level that would be meaningful for me and for my family. And I guess after having children, I kind of – I've got two boys now, and I just, you know, I want them to know where they come from. I want them to be able to connect with their past as well. So I went and looked at roundtrip ticket from Seattle to Montenegro – kind of going more directly – was over $6,000. And so of course, I'm not going to be going to Montenegro. I thought well, it's just that's discouraging. I'm not doing this. I guess the Wyoming information is all I'm ever going to get.

And then right around that same time, Iceland air established service SeaTac airport where I live, and because I had served my mission there, I was a little bit more excited about the fact that they were running some free stopovers in Iceland on the way to Europe. Doing a little bit more research, if I were to go from Seattle to Montenegro through Iceland, the entire flight with that free stopover was $780. And so I immediately hit the enter button, bought the ticket and then told my wife that I was going on this trip.

The only thing that I had with me on this flight over to Montenegro was a few things in my bag. And then these letters that were translated by this patient of mine, spelling out that I'm looking for my great grandparents, and if there's any information they can offer, that would be amazing.

So I took these letters over there and I got off the plane and felt immediately a little overwhelmed. I mean, I couldn't read any of the signs, the people didn't speak English, I just didn't know what I had gotten myself into.

I got transportation up to the town of Niksic, Yugoslavia, which I discovered was the town where my grandfather came from on that death certificate that came back to me from the department of vital statistics in Wyoming. And driving along this kind of main – it's not really a highway, but this this road that kind of heads up towards Niksic is on kind of a mountain ridge.

And there was an adjacent or a parallel ridge on the other side, that just looked pitch black. And all of a sudden that kind of goes really steeply down into the valley where Nicksic – or the city – is. And there was quite a bit of snow on the ground. And for some reason, that was kind of fun to picture my grandfather coming from this place. Because I guess after serving my mission in Iceland, I prefer colder climates. It was really fun for me to kind of see where he came from. And it kind of, I don't know, for some reason, it just brought a smile to my face, knowing that that's where that's the town where he grew up.

So I get into Niksic, and I didn't know where I was going to start, but I saw a church or a cross up at the top of the skyline, and knew that I would maybe get more information at a church then maybe even looking in a phone book where I couldn't read the language, I couldn't even navigate any of anything.

And surrounding this church was a cemetery, almost surrounding the entire thing. And so I went from gravestone to gravestone with the little tablet that I had trying to kind of translate, trying to figure out which one was a Mijušković gravestone, and it took me hours, and I couldn't find one. I mean, and in all of my stuff, I'm tromping through the snow, nothing's happening.

I was a little bit discouraged until I walked around the front of the cemetery, past the church to a funeral home, which I assumed was a funeral home, there was flowers out front, and a nice little lady that was just standing out in front. And I went up to her – because she was smiling – and I went and unzipped my backpack, I handed her one of my letters, and she was nice enough to read it. She called somebody and read it to them, and then she went inside, and I could hear some beeping sounds almost like a fax machine, and then she brought it back out and handed it back to me and blew me a kiss. And that was day one.

So nothing had happened. I was obviously frustrated because she didn't have any information for me. She didn't tell me what the person on the phone said, nothing ever happened with that.

The next day I started going around to the maybe, the government offices in Podgorica, in the capital city. I thought, well, what if I just went to some of the kind of the more government offices and the bigger buildings there just to see if there's somebody that could point me in the right direction. And I ran into this guy named Gordon Stojovic who was a ministry official. And so he invited me into his office, I gave him the letter and he read the letter, but didn't read it all the way. He kind of just read a few of the words and then asked me if I wanted to go and look around the town. In kind of broken English, as best he could, he at least invited me to get into his car. And we went from coffee shop to coffee shop, while he smoked cigars the whole time and telling me all about his beautiful country, and the architecture and everything about this place.

And it was really fun to just kind of hang out with him and to see the city. But I was kind of on a time crunch, and I really needed to find out stuff about my family. So at the end of the day, I said to him, I said, "Gordon, I really love this and thank you so much for inviting me and, and showing me around your town, but I'm really looking for something to do with my family here. If there's any kind of help you can give me." And he goes, "What you look for is miracle." I said "That's exactly what I'm looking for!" And he said, "Well," he said and quote, "The Serbian Orthodox monastery of Ostrog is the most frequently visited pilgrimage site in the Balkans." He said, "Miracles come to those who visit the upper level."

So I thought, "Well, that's exactly what I need to do then. I need to go to this monastery, I need to go to the upper level, maybe my whole family will be waiting for me or there will be open books. It'll all be ready for me and I'll have my entire family history right there and this will be amazing."

So I took a big long journey the next day up to this monastery and it was up closer to wear Niksic was, just at the kind of on the other side of the mountain there. And driving up this road was crazy. If you google this monastery, it's one of the most, I mean, beautiful monasteries you've ever seen. But the road that goes up to it is this crazy, long, windy road, that takes quite a bit of time to get there. There's no railings on the side, the road is cut through the mountain, like through tunnels. And it is, it's quite a journey.

And so I finally get up to the top of this road and get to the monastery, and again, it was almost breathtaking, the way that it's carved out of the mountain, it's painted white, but it literally is carved out of the mountain really high up on this cliff. Again, people come from all over the Balkans to worship their patron saints here. And I was, I was very impressed almost from a, you know, I know when we see our temples, we have that same kind of feeling of awe and beauty, and that's, that's what this felt like to me.

And so I went up there, I knew that I had to get to the highest point of this middle tower, and there wasn't anything there other than there was a candelabra and a couple of photos of Christ on the wall. And that was it. And I thought, "Well, that was not exactly what I was looking for here."

But looking out the window from this perch I, I prayed. And I prayed hard to see if maybe this miracle could really come that I could find something out about my family.

And after about an hour or so it just didn't happen. Nobody came in, nobody talked to me, I didn't see anybody, I didn't see anything else that would indicate anything about my family. So again, once again, discouraged, I went down and got in the car and went to a little coffee shop kind of at the base of the main windy road there in a town called Povija.

And I went into this coffee shop and from the coffee shop, there were three roads that kind of branched out from this coffee shop. One that went up to the Ostrog Monastery, one that went back down to the capital city of Podgorica from whence I came, and then there was another road that went around the back and kind of up – just randomly up the mountain. And it was kind of more of a dirt road, a smaller road. And there was obviously nothing up there.

But for some reason, I decided to go ahead and travel that road. So I drove around the backside of this coffee shop and started going up this dirt road, not knowing where it was going to go. And then it branched off, it went a little bit, there was kind of more of a main road, and then even a smaller dirt road off to the left. And of course I went off to the left.

So I started driving up the smaller dirt road until I run into a guy just standing there in the middle of the road.

And he looked ironically, a little bit like me, he was a little bit bigger guy, he didn't have any hair on his head, he was wearing a big, puffy, blue parka. And, but there was nothing around. There was no car, no bicycle, no motorcycle, I don't know how he even got there. There was no homes, no telephone wires, I just it just looked a little strange having him just standing out there in the middle of the road.

And I did the exact same thing that I did with the lady at the funeral home, I got out of the car, I smiled at him, I handed him a letter. And he read it and did the exact same thing. He turned and grabbed the phone out of his pocket and started calling somebody and reading the letter to them. Halfway through the letter, he points to the letter and says "Mijušković?" And then he pointed to me and said "Mijušković?"

And I started jumping up and down saying, "Mijušković!" pointing to myself thinking that maybe this is it. He understood Mijušković, and maybe he knows something about this. And so he pointed for me to get in my car and to follow him and he started running up this dirt path. So I drive up to a long side of him and point into the passenger side kind of saying, "Hey, you know, would you like a ride?" And he shook his head and kept on waiting for me to follow him. And so I go up this dirt road, he finally tells me to stop. And then to go up even a smaller little path. I mean, this is literally like a little hiking trail up through the brush. And to follow him up into here.

Now, this sounds a little creepy, right? I'm up in the middle of Montenegro and this guy is having me go up into this little trail up into the bushes. And who knows what's gonna happen here, but he just didn't seem like a scary guy. I mean, for crying out loud, he had a good look and haircut, I could trust him. So I get out of the car and follow him up this path. And he points to an old old house. And I mean, I don't even know if you could call it a house because all it really was is rocks and a couple of little partial walls almost really broken down and dilapidated. So he pointed to it and said "Mijušković," and then he pointed to another house on the other side of the trail and said, "Mijušković" and kept pointing to both of these houses saying, "Mijušković, Mijušković, Mijušković." And he almost started kind of hitting his head a little bit and smiling kind of just frustrated that I couldn't understand what he was saying. But he was clearly telling me that these two houses had something to do with the last name or the name of Mijušković.

So we got done with that. He didn't want to keep the letter he handed it back to me and so I drove off and that was the next day. And so that was all that I had come up with. I now just have two photos of these two houses and obviously not a lot of other information.

I get done with this day and I go again through government offices and finally run into the President of the Historical Society in Montenegro. So I thought, "Okay, this guy's got to have something for me, right?" I mean, this guy knows the history of Montenegro. He maybe knows the history of that area, and maybe can tell me a little bit about my grandpa and his family. So his name was Bronco Bondović. And so I go into his office and his secretary was there as well. And then a young girl, she spoke like better English than anybody in the whole country put together this far. So she told me that she was home from school that day and meeting her mom at work, who was the secretary of this Bronco Bondović. So I thought I'd go through her since they didn't speak any English. And she was amazing to just say to them that I was looking for my family, and they read the letter.

And then I showed this Bronco my phone where it had the two photos of these two houses. And he went over and grabbed a book out of a bookshelf and brought it over to me and said to me, that all Mijušković descendants in the world come from two brothers in the late 1600s. And remnants of their home still stand on the Kunak mountainside in the town, or above the town of Povija. And this just completely blew me away. So I assumed that the Kunak mountainside was that road that I had gone up behind the, you know, coffee shop where I was. And that all Mijušković descendants, including me and my grandfather, came from one of those two houses where these two brothers lived. And I just, I can't even explain what this felt like. I was grateful more than anything. I was very grateful at that moment that he knew something about the Mijuškovićs and that I came from one of those two houses.

I was also curious because I have one brother, and I also have two boys. And so there was just that connection, there was the two brothers and I was one of two brothers. And my kids are two brothers. And I don't know, for some reason, this was just a, it almost felt like a family reunion. I almost wanted to hug this guy and I just, but that would have been awkward for him. But I was so excited about all of this and just knowing that maybe I was on the right path here.

And so after meeting with Bronco, the president of the Historical Society, I finally heard back from my patient that had translated the letter for me saying that she had a contact who could maybe help me since he was a UN translator in Montenegro. And he met me in that same building where I was going from door to door trying to find government officials. And when I finally met up with Oliver, it was such a treat because he told me all about Montenegro and the people of Montenegro and the geography and the history. And I was able to understand a little bit better about a little bit more about the country and about my ancestors even and so he offered to make some phone calls for me. And he started with the town that was on that death certificate of Niksić, Yugoslavia, or Niksić, Montenegro.

First one that picked up the phone was a gentleman named Ilija Mijušković. And his name is spelled I-L-I-J-A, which ironically looks a little bit like Elijah, but it is IIija. So we met with him at this Povija coffee shop, the one that I had gone to before at the base of the Ostrog Monastery and Ilija asked if he could question me about a few things about my childhood and about my upbringing. And it was good that we had Oliver there, the UN translator, because Ilijia spoke zero English at all, like he couldn't even say hello. But it really was a fun meeting. And Ilija asked me questions that I just was a little surprised to answer.

He said, he would ask me things like my upbringing and my, my brother, my parents, their birth dates, what I did for a career and what my education was in what classes I took in college, and in my graduate training, I mean, really took to an incredible amount of detail. And after about an hour of this, I said, "Listen, this is amazing." And I asked Oliver to tell him, I really appreciate meeting with him. And it's so fun to meet an actual Mijušković. But I'm really trying to find out more stuff about my family. But then he said, his eyes kind of lit up a little bit and he was not known, he did not smile at all. He had a big furry mustache. And you can tell he was very stern and stuff, but his eyes kind of lit up and said, "Well, let's go down to the cemetery so I can show you some things."

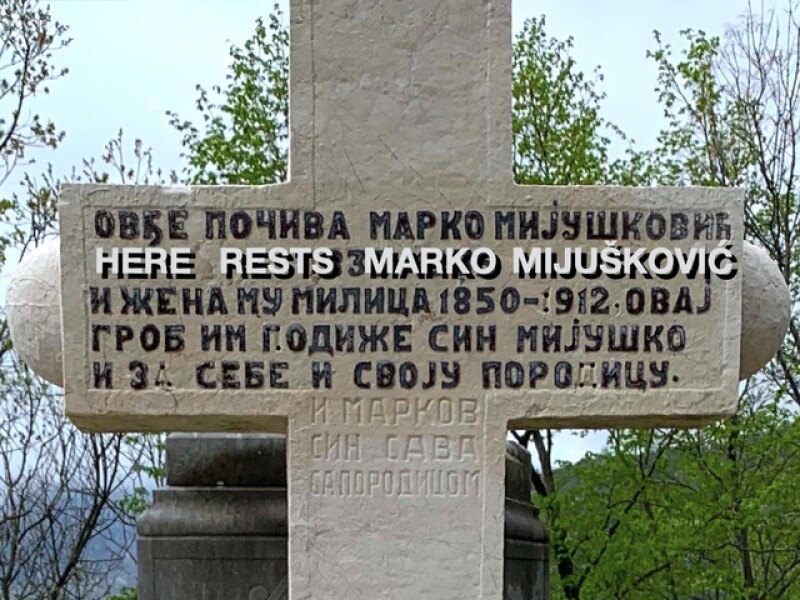

And on the way to the cemetery, he said in these words. He said in the late 1600s, and again about the time that those two brothers were there in those homes, an Ottoman Turkish army executed 72 members of the Mijušković tribe inside a cave fire in the town of Povija and to Mijušković brothers survived. And I just thought, "You know what an incredible story." And Ilija took me to the gravestones and showed me a few things and said that most of the gravestones from my family weren't going to be there because they were all destroyed during these wars. But he said, specifically, "I want to show you this one over here." So we walked me over next to the little chapel that was there.

And this chapel was just tiny. I mean, maybe two people could fit in this chapel. But the gravestone next to it, he pointed to this. And I looked up there and Oliver translated for me, and it said at the very top, "Here rest Marco Mijušković." I looked at the death certificate that I had with me and showed Ilia. And it did indeed show that Joseph's dad, father, was Marco Mijušković. So he told me that this was my great, great-grandfather.

This was really amazing for me to see this, because, you know, obviously not having any other information Besides this, he had passed away in 1912, and was buried in this spot. And to see this was, was very special for me, and to even feel that the DNA inside this cemetery, or inside this grave, was the same DNA that runs through my blood. And I just, that was special for me to kind of be able to connect with my great, great-grandfather in that way, knowing that my grandfather came from this line in this town. And I just felt something really special there.

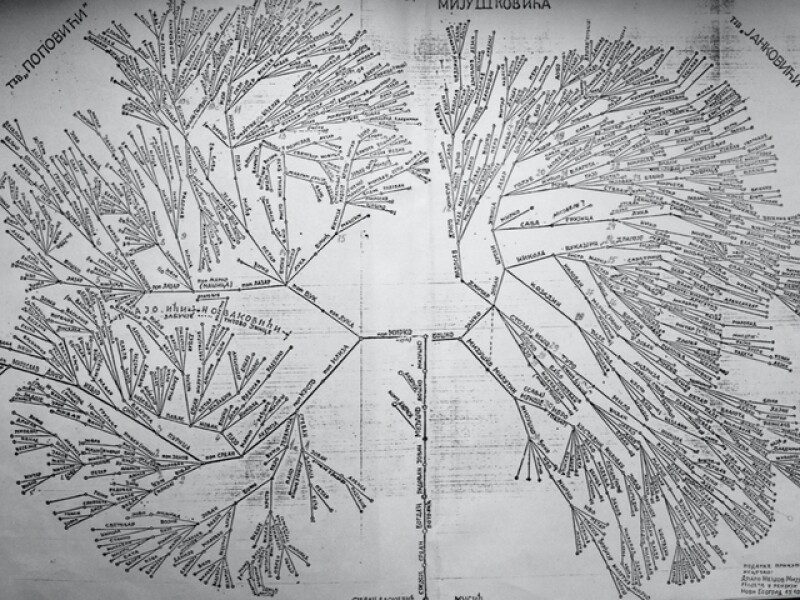

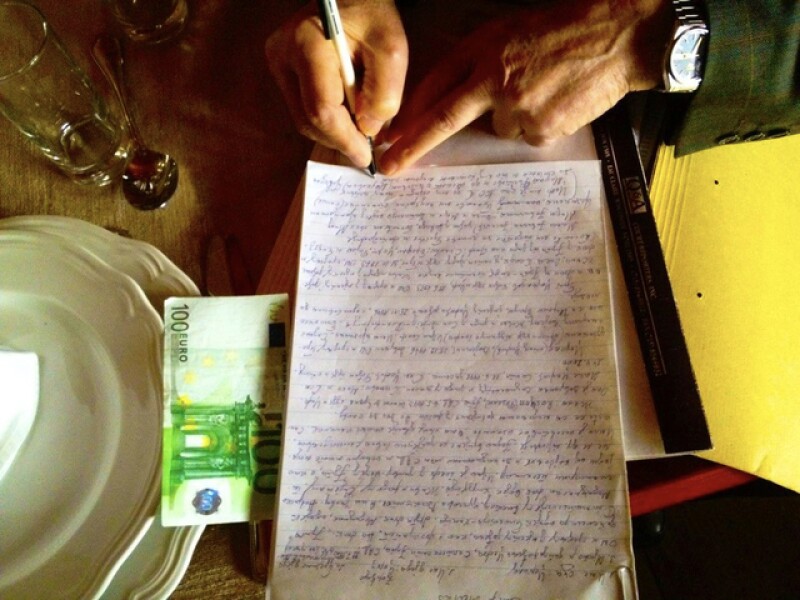

So then I was about to kind of finish things up, I had taken my photos and I basically had spent $780 to go to Montenegro and find my great, great-grandfather, and it was worth every penny for me to see where he was from, I was kind of ready to go. I mean, I had told Oliver and Ilija, I said, "Gosh, this has been great. Thank you so much. I've got to get going here pretty soon. And I really appreciate all this information." And then Ilija was writing some stuff down on a piece of paper, and Oliver said to me said, "Hey, Jeff, you might want to come over here and take a look at this." And I looked down at the piece of paper that Ilija is scribbling on, and it was a family tree, a handwritten family tree of over 1,800, 1,900 names. And it was a pretty large piece of paper.

And I saw, I noticed on this family tree that there was one single track of names that went up, and then branched off with two names, and then huge tree branches off of those two names. And what Ilija explained to me is that the two brothers that lived in those two homes are the two brothers that branch off into these two big trees. Ilija went on to tell me that he has been doing research on the Mijušković family line for 47 years, and that he had put all of this information together on this family tree so that he can eventually publish a book about the Mijušković family name and about all the Mijušković ancestors from the 1200s all the way up until now. What was amazing to me is that he pointed out that one of the brothers was a farmer, one of them was a priest, and that I come from the farmer side of the line.

My heart was exploding, I just I couldn't believe that I had found all of this information, my whole ancestry line from the 1200s all the way up until my my great-grandfather Joseph. He then pointed out that there was a little squiggly line at the end of Joseph's line. And it was the only one on the entire page of 1,900 names. Oliver explained to me that Ilija had been looking for my grandfather all of these years that that was the one link that he didn't have on this family tree because my grandfather had changed his name from Mijušković, to Marks. And that was the one name that he didn't have. And he couldn't complete his book until he knew what happened with Joseph's line. And that's why he asked me all of those questions and wanted to write this book.

We go back to the coffee shop. And he said to me, that he really wants to write this book, but he doesn't have enough money to publish a book. And so I asked him how much it cost to publish a book there in Montenegro. And he said it would be about 100 Euros. So I gave him 100 Euros, which at the time, I think was about $120. And you can tell his eyes got watery. And he said that he was going to dedicate the book to me and wrote down right there and all over translated this. He said, "My brother Jeff Marks gave me 100 Euros to publish the 47-year history of the Mijušković tribe. He came from America to find his family. And we finally found each other."

And this is where it all came true for me where I got to connect with him on a completely different level and that he was looking for me as much as I was looking for him. He had been doing this research for 47 years and was 86 years old at the time. So he wanted to give me these 1,900 names so that I knew where I came from. And in Montenegro, he says that they don't hug but he says that because we're brothers now that we can hug at the end. And so we hugged and now we're family and that was really special. He started calling me his brother, no longer just my name because he says that, and, and Oliver even told me that in their country, brother is a term of endearment And I can only relate to this too because we're members of the Church, but that they call each other brother or sister, even if they're an aunt or an uncle or a distant relative, because they feel a kinship with them. And they share the same DNA, they share the same family stories, the same history. He felt like we are, we're connected in a totally different way. And I was able to really understand him. And he was able to understand me on a totally different level.

But I think his looking for me, for this many years, or at least for my grandfather was very special to him because I came to him, you know, he would have never gone to America to find my family or to find George or his gravestone. But Oliver told me how emotional Ilija was about me connecting to him and now making this whole book happen and his whole story happened and that he was just so grateful that we were able to connect. He wrote me another letter, an email, and I could tell it was done with Google Translate. But it said, "Please come back to our homeland very soon so that we can read, so we can write the history of our brotherhood together. I have your book."

My son, Max, and I went and traveled over to Montenegro to go pick up this book. We met with Ilija and Ilija really sat down with Max and and wanted to tell him about his family's legacy and the legacy of his last name. And not only handed him this beautiful hardbound family history book of not only the 1,900 male names that were on the handwritten family tree that he had. But now we've got women and children in this book, and we're over 3,000-something names. And each one of the members of this family on this family tree have a paragraph inside this book, including me now, because that's why he asked me all those questions.

He also gave Max another book that was just titled "Mijušković" And it was hard bound as well, a little bit thinner. On the inside of this was a picture of the Ostrog Monastery. He told me that my family, specifically my family line, were the protectors of the ostrog Monastery. And this monastery is famous I mean in, in, especially in Eastern Orthodoxy. And so for, for him to say this was really amazing to me. And so he told me a little bit more about the Ostrog Monastery and how our family protected it. And most of our family members died protecting it through these, you know, Turkish invasions all throughout the centuries.

Also, he took Max and me down to the cemetery, again, wherein a monument was erected a Mijušković monument, talking about the people the Mijušković that actually protected the Ostrog Monastery. And that that is their legacy. And so he wanted to do a family picture down there. And so I've got this great shot of Ilija and Max and me sitting at the base of this, this monument.

And I still talk to Ilija, I'm constantly looking for a way to go back and be with him as my family now because with George gone, he's my new brother.

Sarah Blake 33:12

That was Jeff. I hope Jeff doesn't mind if I share that one of the challenges we had in editing his story was that every single detail was important. I would think we can cut this bit about the coffee shop, right? Just for time. But then, nope, that detail and connection were important because they led to the next connection, and the next one and the next one until finally, it led to the connection with Ilija and through him a connection to thousands of his ancestors and relatives.

It is mind boggling to think how Jeff's sort of impulsive decision to go to Montenegro was actually an answer to Ilijas prayers after 47 years of work on his family history. And it is amazing to see how they both were led every step of the way, even in the seemingly random steps by a loving Father who wanted to give them this connection they needed.

Jeff also talked about how in this family history search, he felt like he was working with God to do something that needed to be done. I liked that a lot. And I'm going to keep thinking about it, what it means to be working with God to take the actions that make the connections that tie us closer to our families.

Our next storyteller is KC. You might recognize KC as a previous storyteller, and also he is my husband. His story is about a different kind of family tie that he found closer to home. Here's KC.

KC 34:37

In 1969, my parents built a house in the foothills of South San Jose, California. And about a year later, another couple built a house next door, the Rudd's.

My parents took a plate of cookies over to their house to introduce themselves. And there was an instant connection when it was realized that my dad had been the flight instructor for their son in the Navy. My dad had taught their son Charles to fly fighter jets and trained him to go fight in the Vietnam War. So there was an instant bond between our families. And that bond would grow over the years both through good times and also through a lot of tribulations.

The first of those being that Charles was killed in an airplane crash in Vietnam trying to land on an aircraft carrier in very rough seas in the dark of night. In fact, I'm named after Charles. I was born two years after his death and my parents named me Kevin Charles Blake, in memory of Charles Rudd.

Unfortunately, that wasn't the end of tragedy. A couple years later, Harriet's husband died of a heart attack. My father was the first one over there, helped to move him and administer CPR until the paramedics arrived, but unfortunately he passed. And my mom was there to comfort Harriet during that time.

And then in 1983, my father was killed in airplane crash in Angola, Africa. And Harriet became a listening ear and a source of comfort for my mom as she navigated being newly widowed.

My brothers and I always had a very close relationship with Harriet. In fact, we didn't call her Harriet, we called her Hottie Dot. I think we call her Hottie Dot because our little mouths can't pronounce Harriet at the time and Hottie Dot was what came out. And that stuck. And Hottie Dot was like a grandma to me and my brothers. She was just a warm, loving, and extremely caring person.

I remember going over to her house and she would always have Jazz music playing at her house and she would always have a bowl of cashews sitting on the counter and we eat cashews and listen to Jazz music.

And Harriet came from a rich Italian heritage. And she was always making Italian food and trying to feed us. I remember a frittatas. I remember, rich Bolinas meat sauce over pasta. And it was like having an Italian grandma.

And she was also the person that I ran to when I cut my finger really badly on my Scout knife when I was seven years old and my mom wasn't home. I remember running over there and she was able to bandage it up until my mom could get home and we could go to the doctor and get stitches. And later, Harriet traveled with us to England and toured all over England with my, my brothers and I and my mom. And she just was part of the family.

Harriet was an extremely positive person, she just always was full of hope and happiness. And even in the toughest of times, I remember her saying, "This too shall pass." She just had hope in the future.

And even, even when she contracted lung cancer in 1993. And that year, I remember her, just watching her deteriorate and being a lot of pain. And I would go over to help her with things around her house. And I just remember her still smiling and saying, "This too shall pass."

Harriet didn't have any close living relatives when she died. And so because of this, my mom became the executor of her will and estate. And she had given almost all of her assets to charity. But my mom was in charge of getting her house ready for sale, cleaning everything out and, and just dealing with all of her stuff. And a lot of that stuff just ended up sitting in our garage for years and years. And about eight years ago, I was helping my mom clean out her garage, and I found this old jewelry box. It was locked and I thought it was really intriguing, of course. So I picked the lock and opened it up and it was full of costume jewelry, nothing, nothing valuable. Most of it was really fun 70s broaches and, you know pretty, pretty out of date stuff, but really fun stuff. Anything of value that had been metal or precious stones had been sold before Harriet's death, but there was one item in there and it was a beautiful old pocket watch.

So I was able to do some research on the internet and I found out that this pocket watch made in 1925 was worth a total of about $18 nowadays, which is a real shame when you think of all the craftsmanship and the just the beauty of this piece. But because of that we stuffed everything back in the box and my mom said, "Why don't you take this and your kids can play with it someday?" So I took the box and several years later my daughter became interested in the jewelry box and started pulling out the jewelry and playing with it.

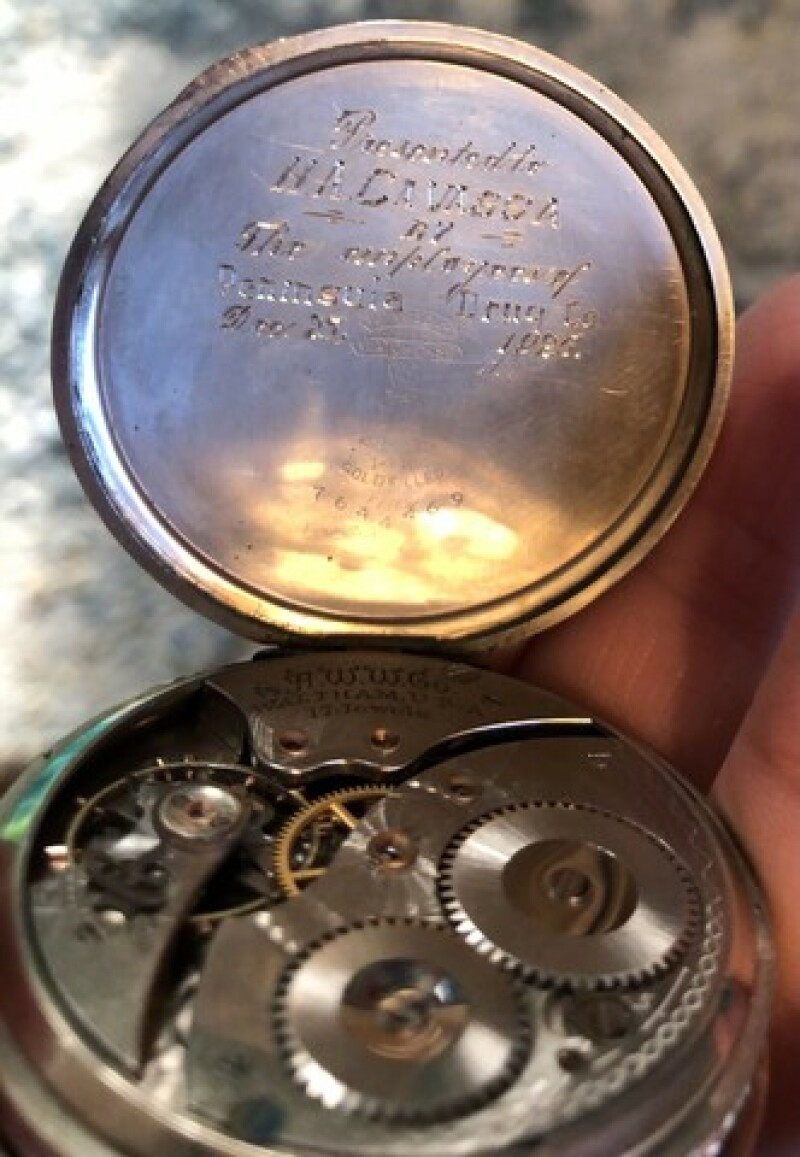

Over the years, that pocketwatch came out dozens of times and we would play with it, but nothing too interesting about it. And then one day, I was looking at it and I realized that the back panel of the watch would pop open. And I'd never realized this before. And inside, you can see all the gears and inner workings and it was beautiful. And then I realized that there was an engraving on the back of that, and it says, "Presented to H.A Cavassa by the employees of Peninsula Drug, December 25, 1925."

Now, I don't think I'd ever heard the name "Cavassa," really before if I had I was younger, but I figured this this must have been Harriet's father. So this was really intriguing. And so we started doing some family history research on on H.A. Cavassa, and we were able to find out that it was Harry A, Cavassa, Harriet's father, and he immigrated from Bologna, Italy around 1895. And he had gone to the University of California, Berkeley and graduated from pharmacology school there.

And in 1904, he started the first pharmacy in South San Francisco. And remember, this is right before the 1906 earthquake, so he would have been there during the earthquake and subsequent destruction of most of actual San Francisco. Now south San Francisco's its own city, but I'm sure that the whole community was affected by that.

And so that drugstore turned into a chain of drugstores called Peninsula Drug, and eventually he married a nurse, Lillian Heifers, who worked for the doctor with whom he shared a building with and they had three daughters. The youngest of which was Harriet. And Harriet, is named after her father Harry, I'm sure that Harry was hoping he'd have a son and he could name that son Harry Jr., but he only had daughters so he had to name one of them after him. And so that's where Harriet comes from.

And Harriet had two children, Charles and another daughter lost to sickness in childhood. And none of Harriet's sisters had children either. And so with the death of Harriet's sister, Marianne in 2001, there was no other living member of this family line.

Since discovering the inscription on the pocketwatch, it really sparked our family's interest in family history, as we've done some of the work for Harriet and her family, and learned more about them, and thought about how our families have been interconnected through the years, and now how our families will be connected through eternity because of, of this bond that we're forming by doing their work.

It's really made me appreciate how important these relationships are. The relationships we have with our family members and those who we choose to make our family members. I know that part of who I am today is definitely because of, I had Harriet in my life and her example. And I love that God chose to create a small miracle by putting that pocketwatch in our way so that we would rediscover that connection with Harriet and her family. I see it as a small miracle in my life to be a part of that.

Sarah Blake 43:14

I am holding Harriet's pocket watch right now. I find it so beautiful. And it also feels a little magical how it just kept showing up until we finally really looked at it and let it lead us to their family.

Someday we will get their temple work done, but for now I have a feeling that it is good just that we remember them – that they're not forgotten. These were people who made connections that mattered all through their lives. Harry A. Cavassa was so beloved by his employees that they chipped in to buy him a nice watch for Christmas in 1925. And Harriet was the one that little Casey ran to with a cut finger, and the one who taught my mother in law how to cook Italian food and to survive as a new widow. In all of these actions, all these connections are the ropes that made them family and that keep us family.

This feels especially poignant to me right now, because here in the United States, it's the week of Thanksgiving, and the Covid–19 pandemic is raging worse than ever. This year, what we thought of as family or traditions or connections are not feeling very normal.

This year, your Thanksgiving dinner might be you eating alone and doing puzzles over zoom. There are thousands of families with loved ones in the hospital who they can't visit or even speak to. So many people are showing love in the most counterintuitive ways this year. By canceling travel plans as my sister just did, or by isolating in a bedroom as my other sister has been doing for the past two weeks, or sleeping in the garage as we hear of health care workers doing so their families won't get sick. And let us never forget the families this year who are coming to terms with a more permanent separation.

President Dieter F. Uchtdorf has said, "Whatever problems your family is facing, whatever you must do to solve them, the beginning and the end of the solution is charity, the pure love of Christ. Without this love even seemingly perfect families struggle. With it, even families with great challenges succeed."

The tie that really binds our families and the rope that anchors and protects us, no matter what our family looks like, is this pure love of Christ. His pure love for us, and his transformative ability to help us love one another. Christ's pure love is strong enough to transform our strange virtual gatherings into holy and happy Places. And I know it is strong enough to turn strangers into family. And it is strong enough to envelop us in the arms of his comfort, even when we feel completely alone.

When I visualize what a family tie looks like, for me, it is a lot more than a shoelace, or an apron string, or even more than a climbing rope. I personally find comfort envisioning a sturdy net made of the kind of crazy knots my little kids tie, quadruple gazillion knotted into a tacky grandma's macro, a hanging plant basket sort of thing.

And I like to imagine that each of the little actions we take makes one more knot in that net, tying us all safely together so that no one has to free solo up these crazy cliffs of 2020.

Whatever your holidays are looking like this year, I hope that you find ways to tie lots of messy little knots between you and all your people. Your biological family who's in the house with you, your church family in their separate homes, the colleagues on your screen and your zoom call, your neighbors and friends and delivery guys and grocery store cashiers – all the people who connect and hold us and give us a sense of place.

This year, I think it's going to take all of our best creativity and positivity and just plain hard work, to feel the connectedness that we crave. And I also think it's going to take a lot of help from our Savior. But I know that we can do it because ultimately whatever our families on earth might look like, we are all children of our heavenly parents and part of their family and being connected to others is what we were made for.

That's it for his episode of This Is the Gospel. Thank you to our storytellers, Jeff and Casey. You can see Jeff's pictures with his son Max and his new brother Ilija at the Ostrog Monastery and pictures of Harriet's pocket watch in our show notes at LDS living.com/Thisisthegospel.

You can also get more good stuff by following us on Instagram or Facebook @thisisthegospel_podcast. All of the stories in this episode are true and accurate as affirmed by our storytellers.

And of course, if you have a story to share about living the Gospel of Jesus Christ, please call our pitch line and leave us a story pitch. The best pitches will be short and sweet and have a clear sense of the focus of your story. Call 515-519-6179 to leave us a message. Finally, if today's stories have touched you or made you think about your discipleship a little more deeply, please share that with us. You can leave a review of the podcast on Apple, Stitcher, or whatever platform you use. And if you can't figure out how to leave a review we even have a little highlight on our Instagram page that can help show you how. Every review helps the podcast show up for more people who need this kind of light in their lives.

This episode was produced by me Sarah Blake, with story production and editing from Erika Free, Katie Lambert, and Casey Blake. It was scored, mixed and mastered by Mix at Six studios. Our executive producer is Erin Hallstrom. You can find past episodes of this podcast and other LDS Living podcasts at LDS living.com/podcast.