As members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, it can be enriching to understand some of the religious practices and experiences of our devout Christian brothers and sisters throughout the world.

Latter-day Saints appreciate the importance of sacred space, but perhaps we’re still growing in our understanding and appreciation of how sacred time—including traditional Christian holidays—can help us focus on the Savior. For many other Christian traditions, sacred time is a way of connecting with the time and places of the life of Christ.

Growing up with a close friend who was Episcopalian, I remember questions about why my Latter-day Saint family differed from other Christians in our celebration of holidays. For example, my friend asked why we didn’t have church on Christmas Day when it fell on a weekday. I hadn’t really considered this question before. In my family, our sacred time was primarily focused on the observance of the Sabbath and the special events of general conference.

Growing up with a close friend who was Episcopalian, I remember questions about why my Latter-day Saint family differed from other Christians in our celebration of holidays.

Of course, growing up, my family celebrated Christmas and Easter in ways that were typical for the United States—putting out milk and cookies for Santa and hunting for Easter eggs. I remember ward members inviting us over for an Easter egg hunt on Saturday to separate it from Easter Sunday, and I recall family friends who had a birthday cake at Christmas so we could remember and celebrate that it was Jesus’s birthday.

Recently, I have noticed that as Latter-day Saints we are becoming increasingly attuned to Christian observances that we haven’t traditionally participated in. For example, in a recent general conference, which fell on Palm Sunday, Elder Stevenson noted, “I observe a growing effort among Latter-day Saints toward a more Christ-centered Easter. This includes a greater and more thoughtful recognition of Palm Sunday and Good Friday as practiced by some of our Christian cousins.”1 And I have noticed Latter-day Saints more often referring to Holy Week as we join with the larger Christian family in marking sacred time through traditional Christian holy days.

Sacred Time

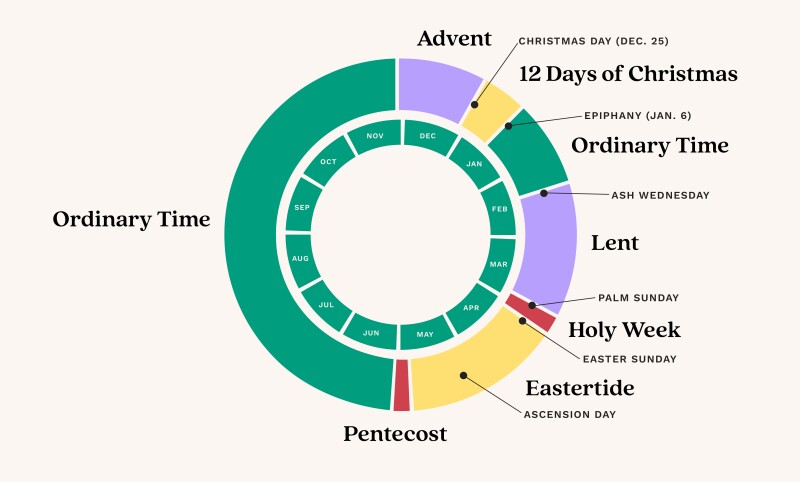

The broader idea of Christian liturgical time is unfamiliar to many Latter-day Saints, so my purpose here is to outline the larger framework that guides many Christian celebrations, as well as some of the feast days (holy days) that are not part of our tradition.

But first, a couple of definitions. The liturgical year is the calendar or schedule of holy days through the year that are part of worship. In Christian tradition, holy days are days that are marked for special celebration and remembrance, and they often commemorate historical events, especially the events of the Savior’s life.

The Christian tradition of marking holy days was preceded by ancient practices of the House of Israel—and Jesus Christ, Himself a devout Jew, observed Jewish sacred times of the year: we read of Christ going to the temple with His family for Passover (see Luke 2:41) and coming up to the temple for the Festival of Tabernacles (see John 7).

After Jesus’s death, the earliest Christians still lived in Jerusalem, so they had access to sacred places to connect them to the events of the life, death, and Resurrection of Christ; for example, the upper room of the Last Supper, Golgotha, and the empty tomb. Christians would visit those places to remember and feel connected to their Lord. But with time, as Christianity spread throughout the world and Christians found themselves far away from the Holy Land, the focus shifted away from holy places and toward sacred time.

As Christianity spread throughout the world and Christians found themselves far away from the Holy Land, the focus shifted away from holy places and toward sacred time.

With the shift from sacred space to sacred time, Christians who were unable to visit the location of Jesus’ triumphal entry in Jerusalem instead celebrated Palm Sunday. Instead of focusing on the upper room location of the Last Supper, Christians commemorated Maundy Thursday and celebrated the giving of the commandment to love one another. And of course, Golgotha, the tomb, and other sites of the Crucifixion and Resurrection would come to be memorialized and experienced during Good Friday and Easter Sunday.

This celebration of sacred time on these holy days led to Christianity developing its own liturgical calendar to commemorate the life of Jesus Christ—even as Christians were further away from Jerusalem.2

▶ You may also like: 5 things Latter-day Saints should know about ancient Christians

Christian Practice

As now celebrated by many Christians, Christmas and Easter are not just one-day holidays. Instead, these two days serve as sacred destinations toward which sacred time is oriented. Easter and Christmas are anchor points in Christianity’s yearlong liturgical calendar, as we will see below. (For definitions of each season and day discussed, see the figure at the end of this article.)

Advent

Leading up to Christmas is the Advent season, which begins four Sundays before Christmas. The word advent is defined as the time of an important arrival, referring to the arrival of Jesus to the earth at His birth. The Advent season culminates with Christmas Eve and Christmas Day, which mark the beginning of the twelve days of Christmas that end with Epiphany, the day celebrating the arrival of the Three Kings. This is a celebration that those who are familiar with Latin American culture have celebrated.

Having a father who served a mission in Germany, my family followed some Advent traditions, including lighting a candle on each of the four Sundays leading up to Christmas and gathering to sing carols. In addition to having many special church services, those who are very careful with their liturgical practices will put up their Christmas tree on Christmas Eve and take it down on Twelfth Night, the eve of Epiphany, since those are the days of Christmas.

Lent

Easter season is likewise preceded by a special and sacred time of anticipation and preparation. Fat Tuesday (“Mardi Gras” in French), known for its carnival celebration in many countries, takes place the day before Ash Wednesday, which begins the season of Lent.

On Ash Wednesday, Christians’ foreheads are marked with ash before they begin forty days of fasting (not counting Sundays) to prepare themselves for Easter. I remember my German teacher from Germany being surprised that my sister and I, who she knew were Christians, had made doughnuts for our school fundraiser during the period of Lent. Her experience of what devout people did was to abstain from fatty treats like doughnuts during Lent.

Holy Week

The season of Lent leads up to Holy Week, which commemorates the events that took place on the days leading up to Christ’s Resurrecton on Easter. In some traditions it is known as Great Week or Passion Week, since it memorializes Christ’s suffering for us (an archaic definition of passion is “suffering”).

While some people are able to physically go to Jerusalem to celebrate these sacred events of the last week of the Savior’s life, through liturgical time Christians everywhere are able to participate and feel close to Christ during this commemoration of His life, sacrifice, and Resurrection. For many people it is an opportunity to review the scripture accounts of what happened on each day, either in their own study or in special church services with readings and celebrations to help worshippers move through sacred time and, through that ritual participation, celebrate the life, death, and Resurrection of Jesus Christ. In church services, the activities and decorations often change to fit the particular day of the week that is being celebrated.

Through liturgical time Christians everywhere are able to participate and feel close to Christ during this commemoration of his life, sacrifice, and Resurrection.

In the last part of Holy Week are the three days called the Paschal Triduum or Easter Triduum. These days celebrate the events of the Last Supper (on Thursday night) through Easter Sunday. These are days of worship through ritual participation and celebration. Some of that participation is in mourning, as many fast on Good Friday, and in some countries there are processions; and some of that participation is in the jubilant celebration of Christ being risen on Easter morning.

Eastertide

Easter Sunday begins a new season: Eastertide. This 50-day celebration leads up to Pentecost—the day of the outpouring of the Holy Spirit as described in Acts 2. In addition, forty days after Easter, the end of Christ’s forty-day post-resurrection ministry is celebrated on Ascension Day.

Other Traditions

Churches that celebrate liturgical time, including Catholic, Anglican/Episcopalian, Lutheran, Presbyterian, and Methodist, will often use certain colors for the clergy’s clothing and for the decorations of their church buildings that correspond to the liturgical season: purple for Advent and Lent, gold and white for Christmas and Easter, red for Pentecost, and green for ordinary time (in the liturgical calendar, the time between the two sacred seasons of Advent/Christmas and Lent/Eastertide is called “ordinary time.”)

Eastern Orthodox Christianity and other Eastern Christian traditions have variations on these sacred times; for example, Orthodox Christians calculate the timing of Christmas and Easter differently. And depending on the tradition, Christians also celebrate additional holy days to commemorate special events or people, such as saints’ days—much like we celebrate Pioneer Day to commemorate our faithful predecessors. Some of these celebrations are personal or on a family level, but many are tied to communal worship in churches, with special readings tied to that day’s place in the liturgical calendar—going back to why my Episcopalian friend asked why we didn’t go to church on Christmas.

Latter-day Saints do not need to necessarily adopt the specific practices of the Christian liturgical calendar, but we can be enriched as we learn about how our Christian brothers and sisters observe seasons of preparation for especially holy days. As part of the global Christian family, we can celebrate these sacred seasons together. The rigorous focus on Christ cultivated by devout Christians through the centuries, expressed in the Christian liturgical calendar, can enrich us and inspire us to keep our mind and hearts focused on the Savior.

The following are descriptions of some of the holy days within the traditional liturgical calendar. They are listed in chronological order beginning with Advent, the first season of the liturgical year.

Advent. The season starting on the fourth Sunday before Christmas. A time of joyful anticipation, remembering the coming of Christ and looking ahead to His eventual return in the Second Coming.

Twelve Days of Christmas. The days between Christmas Day and the celebration of the arrival of the wise men (Three Kings) on Epiphany.

Epiphany. Celebrated on January 6, the Feast of the Three Kings marks the end of the Christmas season.

Ash Wednesday. The beginning of Lent, a time to prepare for Easter. Often people receive a mark of ash on their forehead as they began to fast, hoping to grow closer to God.

Lent. The period of forty days (not counting Sundays) between Ash Wednesday and Easter when people abstain from something in order to grow closer to God.

Maundy Thursday or Holy Thursday. The day before Good Friday, remembering the Last Supper and the giving of the commandment to love one another as Christ loves us. (Maundy comes from an older English word for “commandment.”) In some traditions this includes a ritual washing of feet.

Paschal Triduum. The culmination of Holy Week, starting the evening of Maundy Thursday and ending Easter Sunday evening. It is time of mourning to remember the suffering and death of Christ on Good Friday and also a time of the jubilant celebration of His Resurrection on Easter.

Ascension Day. The 40 days following Easter Sunday, which commemorates Christ’s ascension into heaven after his 40-day ministry among his disciples (see Acts 1:3–11). It is traditionally celebrated on a Thursday, but sometimes the church celebration is moved to Sunday for practical reasons.

Pentecost. Originally an Israelite festival that occurs 50 days after Passover, the Greek term means “fiftieth.” It marks the descent of the Holy Spirit upon the early Christians as described in Acts 2 and is celebrated fifty days after Easter (the seventh Sunday after Easter).

Ordinary Time. The time between the holy seasons of Christmas and Lent and then between Pentecost and Advent are called “ordinary time,” a time for remembering the life of Christ.

Notes

- Gary E. Stevenson, “The Greatest Easter Story Ever Told,” Liahona, May 2023.

- Jonathan Z. Smith notes, “Through schism and conquest, Jerusalem was lost to Christian experience and became, increasingly an object of fantasy. If Jerusalem were to be accessible, it was to be gained through participation in a temporal arrangements of events, not a special one. It was through narrative, through an orderly progression through the Christian year, by encountering the loci of appropriate Scripture, and not by means of procession and pilgrimage, that memorialization occurred” (To Take Place: Toward Theory in Ritual [Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987]).