This article originally appeared in the November/December 2020 issue of LDS Living magazine.

From the beginning, leaders of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints have remained in frequent contact with Church members through various forms of communication. When the Church was formally organized in April 1830, there were already small groups of believers in other parts of New York, including Fayette, Manchester, and Colesville. Business and instruction occurred in conferences and small gatherings. As the number of congregations grew, numerous documents were disseminated to distant Saints in the form of letters, revelations, statements, announcements, epistles, manifestos, memorials, pronouncements, and proclamations. Much of this instruction was published and relayed through Church newspapers and periodicals.

In the early 1830s, more than 800 miles separated the two centers of gathering designated by the Lord—Kirtland, Ohio, and Jackson County, Missouri. This physical distance required steady correspondence between leaders in Ohio and Missouri. Even after the Saints moved west to settle in the Rockies, letters and Church-published newspapers and periodicals remained the primary mode of communication with the worldwide membership of the Church until the advent of electronic communications in the late 20th century.

As colonization in the west extended and branches of the Church were established across the globe, the need for communications between headquarters and outlying branches increased. Mission presidents and others relied on circulars, personal correspondence, and periodicals to remain current on new announcements, directives, and revelations. While some of these communications were intended for ecclesiastical leaders, others kept the general membership informed and built a connection between headquarters and the rank and file. Messages from the First Presidency have been published in books and issues of Church magazines. Additionally, some messages have been reflected in general handbooks over the years and, more recently, posted to the Church’s website or sent by email.1 These communications and messages vary in their degree of importance, ranging from major policy adjustments to direction regarding mission expenditures. Some have been canonized as scripture while others have been superseded several times by new instruction.

In recent years, documents bearing the title of “proclamation” have received lots of attention and visibility. Since 1980, three proclamations have been introduced at general conference. The prominence of these documents sometimes promotes an oversimplified grouping of proclamations valued above other communications. While it is tempting to retroactively link past and recent proclamations, modern observers should be careful not to inflate the importance of titles or marginalize other key communications from Church leaders.

A brief study of the circumstances and context surrounding early proclamations illustrates differences in purpose and how they relate to other messages not designated as proclamations. A close look at the recent proclamations reveals a much different purpose than those from the 19th century.

Nineteenth-Century Proclamations

In January 1841, the First Presidency—Joseph Smith, Sidney Rigdon, and Hyrum Smith—wrote what appears to be the first document identified as a proclamation, from Nauvoo, Illinois. It was published in the Church’s newspaper, the Times and Seasons, and addressed to “the Saints scattered abroad” in Europe to provide a progress report on conditions in Nauvoo and urge converts to emigrate to their new city on the banks of the Mississippi. After reporting that the Illinois state legislature had recently passed a charter creating the city of Nauvoo, the First Presidency called upon “all who can assist in establishing this place, make every preparation to come on without delay” to “strengthen our hands, and assist in promoting the happiness of the Saints.”

It also discussed the urgency to complete the Nauvoo Temple through the “great exertions” of the Saints. Those willing to sacrifice their homes and gather to Nauvoo were promised to be welcomed as friends and be blessed for uniting with their fellow Saints in the Lord’s work.2

This proclamation was issued during a momentous chapter in the early history of the Church. Two members of the Twelve had first preached the gospel in the British Isles in 1837. Joseph Smith sent the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles to the British Isles from 1839 to 1841 in answer to a revelation from the Lord (only nine of the Twelve answered the call). When the First Presidency published their 1841 proclamation, members of the Twelve were nearing the completion of their mission that brought over 6,000 converts into the Church. Many of these converts heeded the call to gather to Nauvoo, helped build the temple, and followed the Twelve west to settle Utah.3

Another proclamation was published in April 1845, nine months following the murders of Joseph and Hyrum Smith in Carthage. Authored by the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles (who served as the presiding body of the Church following Joseph’s death until December 1847), it was issued in partial fulfillment of a January 1841 revelation directing Joseph Smith to “make a solemn proclamation of my gospel” to “all the nations of the earth” (D&C 124:2–3). Published as a 16-page pamphlet, the document boldly declared to “all the Kings of the World, to the President of the United States of America . . . and to the Rulers and Peoples of all Nations” that God’s kingdom had been restored to the earth by “authority from on high.” It called upon all to repent, embrace the restored gospel, and prepare for the Second Coming. Governmental leaders were encouraged to devote all available resources to building the Kingdom of God. The Twelve closed the proclamation with brief testimonies of numerous gospel principles.4

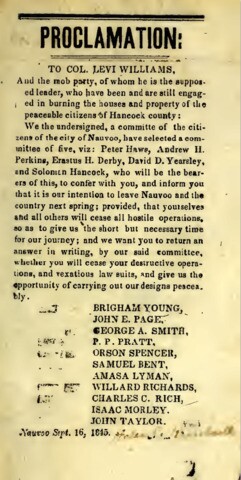

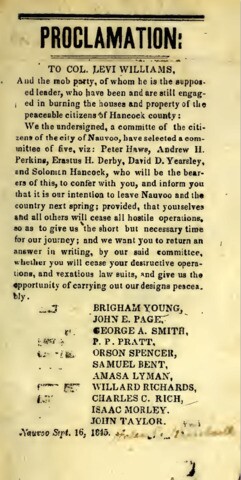

Five months later, Brigham Young and a committee of Nauvoo citizens, including several members of the Twelve, published a proclamation directed to Levi Williams and others guilty of “burning the houses and property” of the Saints in Hancock County, Illinois. By the fall of 1845, persecution in and around Nauvoo intensified as enemies resorted to arson and mob violence to remove the Saints from the region. In the proclamation, Church leaders promised to leave the region “next spring” if their attackers would “cease all hostile operations” to provide them the “necessary time [to prepare] for our journey.”5 Continued harassment accelerated their departure with the first companies leaving Nauvoo in February 1846. Interestingly, William Clayton referred to this proclamation as a letter, suggesting that the categories of communications during this time were interchangeable.

Brigham Young issued several proclamations in his capacity as governor of Utah Territory in the 1850s. The most well-known of these was a proclamation declaring martial law in the territory in 1857 as the U.S. Army approached Utah to squash a perceived rebellion.

Additional proclamations were published by Church leaders as they traveled abroad on assignments. For example, while overseeing missionary activity in the Pacific, Elder Parley P. Pratt sent proclamations to those on the coasts and islands of the Pacific Ocean as well as citizens of Latin American nations.6 These became important missionary tracts as more than 100 elders were called to take the gospel to the four corners of the earth—including Australia and Hawaii—at a conference held in August 1852.

An 1865 proclamation was the first endorsed by both the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve Apostles and it is the noticeable outlier when compared to other proclamations. Its purpose was twofold: (1) to recall copies of Lucy Mack Smith’s history previously published by Elder Orson Pratt, and (2) to publicly rebuke Elder Pratt for his objectionable teachings and speculation related to the nature of God. The proclamation appeared in the Church’s major publications—the Deseret News and the Millennial Star. Pratt’s theories were published “to the world as facts, and as doctrines” without the authorization of the First Presidency and Twelve. The core message in the proclamation’s reprimand of Elder Pratt was that “no member of the Church has the right to publish any doctrines, as the doctrines of the Church” for “there is but one man upon the earth, at one time, who holds the keys to receive commandments and revelations for the Church.”7

Subsequent censures of Church leaders were not announced by proclamations. Discussions with individuals more often occurred in private meetings and resulted in the issuing of public apologies by individuals. For example, two years after the Elder Pratt episode, Elder Amasa M. Lyman of the Twelve published an apology to Latter-day Saints for his false teachings relating to the Atonement of Jesus Christ.8 More recently, in 1991 the late emeritus general authority Elder Paul H. Dunn wrote a letter to Church members that was printed in the Church News seeking forgiveness for embellishing stories in his public talks and writings.9

Recent Proclamations, 1980–2020

The use of the term “proclamation” was revived by Church leaders in 1980 to commemorate 150 years since the formal organization of the Church on April 6, 1830. Anniversary messages had been prepared by previous First Presidencies in 1930 and again in 1947 to mark the Church’s centennial and the arrival of the first pioneer companies in Utah. The content of the 1930 message was similar to the 1980 and 2020 proclamations, with the First Presidency focusing their message on events preceding the Restoration, the First Vision, restoration of the priesthood, and organization of the Church.10

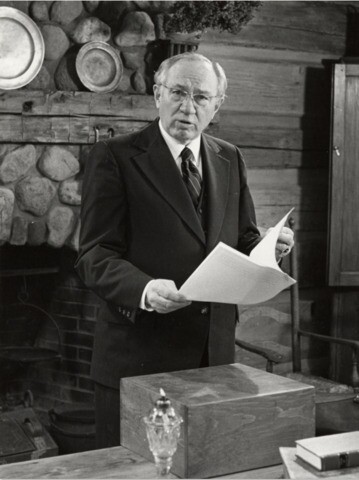

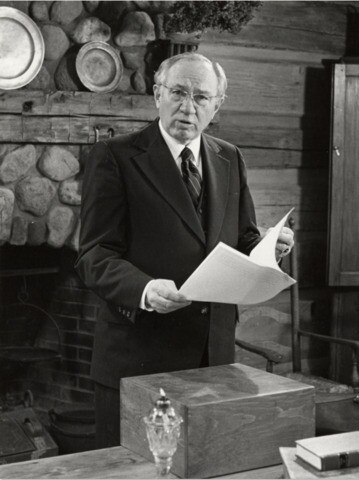

However, the April 1980 general conference was unlike any other. To commemorate the 150th anniversary of the organization of the Church, conference sessions originated from two locations—Temple Square and Fayette, New York. Broadcasting live in locations some 2,000 miles apart posed logistical and technological challenges. In anticipation of the milestone, the Church constructed two buildings at the Peter Whitmer farm in Fayette: a log cabin representing the Whitmer home where the organizational meeting took place on April 6, 1830, and a meetinghouse with a visitors’ center.

Plans were made to dedicate the structures and present a proclamation at general conference. Following the Saturday morning session of conference, President Spencer W. Kimball and Sister Camilla Kimball, along with Elder Gordon B. Hinckley and Sister Marjorie Pay Hinckley, boarded a plane and flew to New York. The Sunday morning session of conference began in the Tabernacle and then switched to the Whitmer cabin, where President Kimball spoke briefly before inviting Elder Hinckley to read a proclamation to commemorate the organization of the Church on that precise day 150 years earlier.11

The proclamation was prepared by the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve Apostles and became the first of its kind to be presented in a general conference. It affirmed that “The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is in fact a restoration of the Church established by the Son of God,” built upon a foundation of prophets and apostles with Jesus Christ as the chief cornerstone. It further declared the truthfulness of the Book of Mormon, restored doctrines, and temple ordinances.12

In the 1990s, Church leaders again felt inspired to create a proclamation, this time regarding the family and its central role in God’s plan. Elder Dallin H. Oaks recalled that “subjects were identified and discussed by members of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles for nearly a year.” Direction was prayerfully considered “on what we should say and how we should say it.” A committee composed of three members of the Twelve—Elders James E. Faust, Neal A. Maxwell, and Russell M. Nelson—was appointed to draft the text, which was eventually presented to the First Presidency for their revisions. It was approved shortly before President Howard W. Hunter died, but as the newly set apart prophet, President Hinckley decided not to share it with the Church at the April 1995 general conference. Instead, he presented “The Family: A Proclamation to the World” six months later during his address at the general Relief Society session of conference.13

Church members at the time were not surprised by the teachings presented in the proclamation. Years later, however Sister Bonnie L. Oscarson observed, “Little did we realize then how very desperately we would need these basic declarations in today’s world as the criteria by which we could judge each new wind of worldly dogma.” She added that “the proclamation on the family has become our benchmark for judging the philosophies of the world.”14

Following its release, framed presentation copies of the proclamation on the family soon adorned the walls of many Latter-day Saint homes and meetinghouses. This visible reminder cemented the term “proclamation” in Latter-day Saint vernacular. But doctrinal statements made by the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve Apostles already had precedent. Previous doctrinal statements released by Church leaders include the Articles of Faith, as well as a detailed explanation of the Godhead published by the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles in 1916 to clarify the roles and titles of the Father and the Son.15

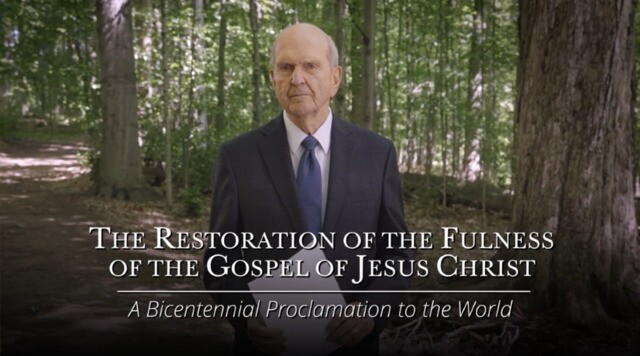

The year 2020 has been a memorable one as the Church celebrates the 200th anniversary of the appearance of God the Father and His Son Jesus Christ to Joseph Smith in what is known as the First Vision. Similar to the 1980 proclamation, a bicentennial proclamation was presented to the Church during the Sunday morning session of the April 2020 general conference by President Russell M. Nelson.16

This time, instead of broadcasting live from a historic site during general conference, President Nelson was prerecorded reading the proclamation in the Sacred Grove. This segment was played during his conference address and powerfully connected viewers to sacred space as they watched President Nelson near the place where the First Vision occurred.

Don’t Judge a Document Solely on Its Title

Aside from previously discussed examples of messages similar to proclamations, there are several other documents with the characteristics of past proclamations. A pair of messages to the world were shared in the first half of the 20th century. At the dawn of the new century, President Lorenzo Snow delivered a “Greeting to the World,” reflecting on the accomplishments of the past century and expecting “grand events to occur in the twentieth century,” as it would be “the grandest of all the ages of time.”17 In 1935, the First Presidency released a “testimony to the world” at what was referred to as the close of a century of “God’s true church.” They emphasized two great truths that must be accepted by all mankind—the Atonement of Jesus Christ and the restoration of the holy priesthood and the gospel.18

Few, if any, communications from Church leaders have had more impact than two declarations (not proclamations) now included in the Doctrine and Covenants. Official Declaration 1 is a manifesto received by revelation to President Wilford Woodruff in 1890 that led to the end of the Church’s practice of plural marriage. A second declaration is a 1978 revelation given to President Spencer W. Kimball that extended the priesthood to all worthy males regardless of race. This opened doors for the gospel to extend its reach to all nations, kindreds, tongues, and people.

In January 2000, the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve published “The Living Christ: The Testimony of the Apostles” to commemorate the birth of the Savior Jesus Christ. While not called a proclamation, it closely resembles the proclamation on the family in both appearance and purpose, and framed copies of “The Living Christ” also decorate many Latter-day Saint homes. At the time “The Living Christ” was issued, Elder Russell M. Nelson explained that it was a pronouncement issued by the Apostles that year in an effort “to leave something that would get into the hearts of people and endure, even beyond the life of those testifiers.”19

Over the years, the meaning and purpose of proclamations has evolved. For Latter-day Saints today, they represent authoritative declarations by the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve to recognize significant anniversaries or declare doctrine. But the true importance of recent proclamations lies not in the term “proclamation” but in the shared authorship and unanimity of all 15 prophets, seers, and revelators.20

It is important to keep in mind that hundreds if not thousands of communications have played important roles in forming a connection to Church leaders, maintaining administrative uniformity, and declaring God’s will to Saints both near and far. There will likely be additional proclamations in the future as determined by the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. Each should be viewed within their proper context and appreciated as a complementary addition to the cornucopia of messages intended to edify the Saints and confirm the ongoing Restoration and revelatory nature of the Lord’s Church.

Brandon J. Metcalf is an archivist with the Church History Department of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Lead image a screenshot. All other photos from the Church History Library

Notes

1. See for example James R. Clark, ed., Messages of the First Presidency of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1833–1964, 6 vols. (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1965–1975); Reid L. Neilson and Nathan N. Waite, eds., Settling the Valley, Proclaiming the Gospel: The General Epistles of the Mormon First Presidency (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017); monthly messages by members of the First Presidency were published in the Ensign and other Church magazines until April 2018.

2. “A Proclamation to the Saints Scattered Abroad,” Times and Seasons 2, no. 6 (January 15, 1841), 273–277; this soon reached the British Saints being published in the Millennial Star 1, no. 11 (March 1841), 269–274.

3. See James B. Allen, Ronald K. Esplin, and David J. Whittaker, Men With a Mission: The Quorum of the Twelve Apostles in the British Isles, 1837–1841 (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1992).

4. Proclamation of the Twelve Apostles of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (New York City: Pratt and Brannan, 1845).

5. Proclamation to Col Levi Williams, and the mob party, of whom he is the supposed leader, Nauvoo, September 16, 1845, Church History Library.

6. Parley P. Pratt, Proclamation! To the People of the Coasts and Islands, of the Pacific; of Every Nation, Kindred and Tongue by an Apostle of Jesus Christ (Sydney: C.W. Wandell, 1851); Parley P. Pratt, Proclamacion! Extraordinaria, para los Americanos Españoles, or Proclamation Extraordinary! To theSpanish Americans (San Francisco: Monson, Haswell, 1852).

7. “Hearken, O Ye Latter-day Saints, and All Ye Inhabitants of the Earth Who Wish to be Saints, to Whom This Writing Shall Come,” Deseret News (August 23, 1865), 372–373; also published in the Millennial Star 27, no. 42 (October 21, 1865), 657–663. Aside from Orson Pratt, Daniel H. Wells, second counselor in the First Presidency, was the only member of the First Presidency or Quorum of the Twelve Apostles not listed as a signer of the proclamation. Wells was in England at the time presiding over the European Mission.

8. Amasa Lyman, “To the Latter-day Saints throughout all the World,” Deseret News (January 30, 1867), 4.

9. Paul H. Dunn, “An open letter to the members of the Church,” Church News (October 26, 1991), 5.

10. “A Message,” Improvement Era (May 1930), 453–458.

11. Dell Van Orden, “Fayette links past, present of Church,” Church News (April 12, 1980), 5–6; Sheri L. Dew, Go Forward with Faith: The Biography of Gordon B. Hinckley (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1996), 367–370.

12. “Proclamation: From the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, April 6, 1980,” Conference Report (April 1980), 75–77; also published in the Ensign (May 1980), 52–53.

13. Gordon B. Hinckley, “Stand Strong against the Wiles of the World,” Ensign (November 1995), 101; “The Family: A Proclamation to the World,” Ensign (November 1995), 102; Dallin H. Oaks, “The Plan and the Proclamation,” Ensign (November 2017), 30; Sheri L. Dew, Insights from a Prophet’s Life: Russell M. Nelson (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 208–210.

14. Bonnie L. Oscarson, “Defenders of the Family Proclamation,” Ensign (May 2015), 14–15.

15. Joseph Smith, “Church History,” Times and Seasons 3, no. 9 (March 1, 1842), 709–710; First Presidency and the Council of the Twelve Apostles, “The Father and the Son: A Doctrinal Exposition by the First Presidency and the Twelve,” June 30, 1916, as published in the Improvement Era (August 1916),

16. Russell M. Nelson, “Hear Him,” Ensign (May 2020), 91–92.

17. Lorenzo Snow, “Greeting to the World,” address delivered at the Centennial Services, January 1, 1901, Church History Library.

18. “A Testimony to the World,” Improvement Era 38, no. 4 (April 1935), 194–195.

19. Sarah Jane Weaver, “An enduring testament of the living Christ,” Church News (April 15, 2000), 11.

20. See Dale G. Renlund and Ruth Lybbert Renlund, The Melchizedek Priesthood: Understanding the Doctrine, Living the Principles (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2018), 37–39.