Walter Rane selects a paintbrush from a tin can. The thin wooden tool fits in his hand so naturally it seems to be an extension of his fingers. Dabbing at the collection of colors on his palette, he brings brush to canvas.

With each stroke, a soft scratching sound whispers throughout the room. Minutes turn into hours, but Walter doesn’t keep track of time. He lives to create, and the possibilities are endless: a cityscape beneath blue clouds tinged with sunlight, angels cascading from the sky like water, a magnolia tree in full bloom in spring, the resurrected Christ descending from the air.

For Walter, eating is a burden; he hungers for art. Adding another brushstroke to the canvas, he coaxes the bristles to bend beneath his touch. He pauses—listening, perhaps, to what the painting is saying—and considers where it should go, and how he can take it there.

The process may be observed by few, but Walter’s paintings have caught many an eye as his works have inspired people worldwide. Today, 14 of his originals are displayed in temples of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, from Rome to Palmyra to Barranquilla. Ten originals hang in the Conference Center in Salt Lake City, and 14 of his Book of Mormon paintings are displayed in the meetinghouse below the Manhattan New York Temple. In total, the Church History Museum has a staggering 72 pieces by Walter in its collection, including paintings, etchings, and preparatory drawings for paintings. And that’s not to mention the works housed in many buildings on Temple Square as well as the Nauvoo Visitors’ Center and the Whitmer Farm.

But of even greater consequence than the number of paintings Walter has created for the Church is what he has accomplished through his pieces: By bringing new life to religious art for Latter-day Saints, he has invited countless viewers to deepen their faith.

A Young Artist

Walter can’t remember a time when he didn’t love art. Born in Southern California in 1949, it was evident early on that Walter had a talent for what would later become his profession in life. His mother even saved a note from his kindergarten teacher who had spotted his ability.

“I don’t know if that’s just because I wasn’t good at anything else,” jokes Walter, “[but my teacher] was encouraging me. And you know, that stuck, and all through school it just became part of my identity, really. And I always loved it, so it wasn’t a burden or anything. . . . I still find it exciting.”

Walter’s parents fostered their son’s passion, giving him art kits for Christmases and birthdays, as well as art history books about the old masters from the Renaissance like Rembrandt and Rubens. He was captivated by their work and soon became attached to the classical figurative style. His talent also quickly grew; at around age 10, he says, he “started ignoring the numbers on paint-by-number [kits],” so his parents bought him art supplies instead. Taking classes in a variety of mediums both in and outside of school, he experimented in sculpture, collage, and carving, but oil painting was always his greatest interest.

And yet despite his love for classical art, Walter decided as early as middle school that if he was going to make a living through his passion, illustration would be more practical. While abstract pieces by 1960s artists like Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning were highlighted inside major magazines, Walter’s parents had observed that illustrations were often featured on the covers of publications like The Saturday Evening Post. So he set his sights on studying at the ArtCenter College of Design in the Los Angeles area, which specialized in career-oriented arts.

Before pursuing his career, Walter left for a mission in France the day after he turned 19. At one point during his service, he and another elder were asked by their mission president to create a mobile visitors’ center. Walter made several pieces of artwork and collected Church posters for the open-air exhibit, taking it around their mission and giving tours. As part of their efforts, they set up the center near the Eiffel Tower on the Place du Trocadero, and a local newspaper and the Church News each printed an article about it.

After his mission, Walter pursued his studies at the ArtCenter College of Design. Upon graduation at age 24, the aspiring artist then set off in his Ford Falcon and began the long drive across the country to work as a freelance artist in New York City. But before he arrived in the Big Apple in 1974, he wanted to make a short detour.

“I stopped in Salt Lake [City] and tried to show my portfolio, but there was nobody to show it to. The Church didn’t use visual arts much, and what little they did, they had the Harry Anderson and Arnold Friberg paintings. They didn’t seem to see a need for any other, so the idea of doing religious art . . . I just kind of tucked it away as not being practical,” he says. So Walter went on his way again—only his car “blew up” in Iowa, and he had to borrow money from his father in order to purchase a Volkswagen Beetle, which he drove to New York.

The City Life

Painting on the side when he settled in New York City, Walter wasted no time finding work as a freelance illustrator for book and magazine publishers. By day, his clients included well-known companies such as Random House, National Geographic, and Reader’s Digest. His range of styles was likewise diverse, and he illustrated classic books and children’s stories alike, from a 1978 version of William Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom! to American Girl’s Meet Kit series. There was nothing Walter couldn’t illustrate, and he enjoyed the craft of telling a story through pictures.

“I did a lot of reading of detective novels and adventure novels . . . I tried to visualize what was going on and what would sell the book,” Walter says. “If there was a drawback to [freelance] or a frustration, it was that I was basically a hired hand—the paintbrush for somebody else’s ideas. So they weren’t what you would call self-expression. I was just using the techniques and skills of the artist but doing work for hire.”

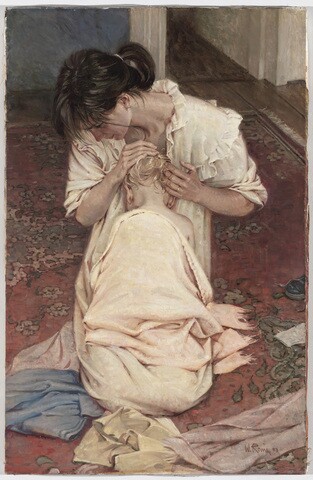

Whenever he could, Walter dipped into his oil paints for pleasure, selling a piece here or there on the side. While living in Manhattan, he met Linda Carlson, who had moved to the city after graduating from Brigham Young University in art. When the two married and started a family, he often captured the beautiful everyday moments of their lives. The scenes were simultaneously sweet and simple: In Mother and Child, Linda holds their son after his bath, a towel draped around his shoulders while his small frame leans into her. In Peter and Mark Drawing, two of their boys huddle over sheets of paper on the floor as they cover the white pages with yellow, green, blue, and red streaks of crayon to their hearts’ content.

It was after about 20 years of working in illustration, which included a move to Connecticut, a yearlong hiatus with his family in Paris, and the births of two more sons, that things in the publishing industry started to shift. Computers became more and more convenient for production purposes, so demand for traditional art declined. Preferring paintbrush, board, and canvas to mouse, keyboard, and screen, Walter began thinking of transitioning away from the illustration world and starting afresh somewhere else.

A Turning Point

Moving across the country with his family to Oregon, Walter painted landscapes and taught for a living. Art galleries up and down the West Coast sold his paintings, but his career still wasn’t getting the traction he had hoped for. That would all change in the ’90s, when Walter submitted the piece Mother and Child to the Church’s First International Art Competition. Richard Oman, who began the competition in an attempt to diversify the Church’s art collection to embrace the world church, fondly recalls Walter’s submission.

“Obviously, he was deeply in love with his wife and his family, and that showed in his work. It was also a superb piece of figurative artwork. He really knew how to do figures and people. That’s not a given. Many artists in our time lack those kinds of skills. . . . He had highly refined skills. In addition to that, the color harmonies were very, very sensitively done and beautiful,” he says.

Although that piece stayed in Walter’s personal collection, he continued to submit to the Church’s art competitions. One was a religious painting of the Christ child observing Joseph working as a carpenter. The Church History Museum purchased it, which led to Walter’s first commission for the Church in the late ’90s of a painting depicting the resurrected Christ addressing Mary outside the tomb. It originally hung in the visitors’ center in Winter Quarters, Nebraska, and is now displayed in the Conference Center.

Oman, who was a senior curator for the Church History Museum for 40 years and served as a member of the Temple Art Committee for 25 years, says he and his colleagues were thrilled to discover Walter for multiple reasons. Not only was he a skilled artist who could paint figures—a very necessary component in Church art—but he was also a faithful member of the Church, which showed in his paintings.

“We thought, ‘This wonderful artist is a godsend to expand our ability at the museum,’” he says. “And he has not let us down. He has done wonderful works.”

Walter says a large part of his success was timing, as the Church began acquiring his pieces during a building boom of temples, visitors’ centers, and the Conference Center. Whether the Church commissioned him for a specific piece or he painted something on his own and showed it to the Church, Walter began working on religious paintings regularly.

“When that happened, it definitely was a life-changer for me,” he says. “The origins of my interest in art was religious artwork of the old masters, and so it became an avalanche of ideas.”

Those ideas have brought about many paintings over the years. From the Old Testament to the Doctrine and Covenants, Walter has covered so many scripture stories that Latter-day Saints have likely seen his work without even realizing it. But it isn’t just his skill as an artist that makes Walter’s paintings stand out from among the rest—equally exceptional is the perspective, passion, and emotion he brings to the canvas.

Expressing Emotion

Paintings that are centered on emotion haven’t always been a focal point in Church art. According to Church History Museum curator Laura Howe, an illustrative tradition was established in the Church as early as the 1960s with Arnold Friberg, who was known for his pre-visualization paintings for the highly acclaimed film The Ten Commandments. Not long afterward, the Church tapped into artist Harry Anderson—an illustrator who was not a member of the Church—who later painted well-recognized works like The Second Coming and John the Baptist Baptizing Jesus.

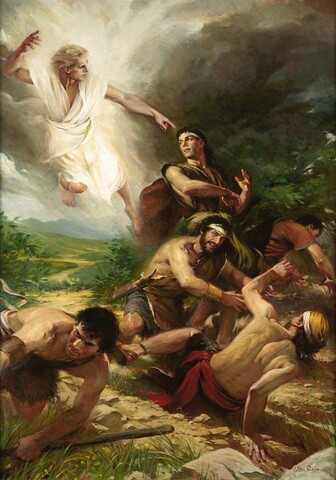

These paintings, Howe says, became prevalent in the Church and were used in meetinghouses, magazines, Sunday School, and Primary. So when Walter came on the scene, his illustrative background made his paintings feel familiar. But, contrary to the style of many illustrators, he introduced motion in a Baroque fashion that hadn’t been seen before—and the result was striking. For instance, in Alma Arise, an angel robed in white swoops down into the painting in a diagonal line from stormy clouds, his finger just inches from touching Alma the Younger’s head while the sons of Mosiah cower on the ground.

“I love it. Every other time you see an angel in Latter-day Saint tradition, they’re standing very nobly in the air,” Howe says. “And [what] I’ve heard [Walter] say once is, ‘Why are they always standing? That’s not how I imagine angels. They would be coming out. They’re flying. They’re moving.’ And I think that’s true of all his works. There’s always a bit of theatricality, a little bit of drama, and so I think it allows people to connect with them on a different level.”

Walter’s oldest son, Peter Rane, says his father’s paintings are also a reflection of his testimony, and his interpretation of angels is therefore even more personal.

“He himself has said [that] he doesn’t know how an angel looks when it’s moving. He doesn’t know if it’s actually doing those motions. But the emotion that is expressed when he paints it that way—I feel something that’s less rigid,” Peter says. “I appreciate that looseness of allowing ourselves to explore our testimonies in our own way and understand the uniqueness of our testimonies.”

Walter’s capacity to show movement and energy makes his scenes more relatable, says temple art curator Hannah Miller. The people he depicts, she says, are “not like amateur actors in a play,” but instead “are real people encountering these miracles.”

Collector Brad Pelo has seen up close the lengths that Walter goes to in order to put emotion into his work. In the early 2000s, Walter started on a commission to create 16 paintings of scenes from the Book of Mormon. While aware that the locations of the Book of Mormon are unknown, he hoped that traveling to Central America would help him find inspiration for his work. Pelo accompanied him, and while there, Walter photographed and sketched, capturing expressions and using the material to re-create powerful scenes from scripture. After the trip, Walter then moved back to New York City to be near museums so he could observe and be inspired by great works of art.

Pelo now has several of Walter’s originals in his home. His family has moved often over the years, he says, but no matter where they end up, Walter’s paintings make them feel at home.

“They bring to the heart of our family those most important eternal events around God’s plan for us. So it brings not only the spirit of beauty to our home, which original artwork always does, but it brings this anchoring to our family that we love,” he says.

Painting a Narrative

Walter is also admired by many for the way in which he brings scripture stories to life. Oman explains that other media have the capacity to use audio and movement, but artists must do the opposite and freeze time in a painting—therefore, picking the right moment to capture is all the more important.

“In many ways, [Walter] is our finest painter of dynamic figurative movement in the Church,” Oman says. “He depicts the moment before [an event], and your subconscious continues the movement to the conclusion and you reach the moment that would be after what he’s depicted. And in the process, movement happened and you yourself were part of the experience.”

Walter often welcomes viewers into his art by leaving an open space in his paintings where people can metaphorically insert themselves into the scene. Whether it’s his depiction of the Savior sending forth the Twelve Apostles or his version of the Last Supper, Howe says Walter “invites you into the piece” and “gives you a place to enter in.”

Approaching a scene like the Last Supper can be daunting, Walter says, because it has been done so many times before. However, he still feels compelled to tackle it.

“It’s also about expressing myself, [that] ‘This is my testimony that this is a real thing. This happened.’ And it might not be as good as what somebody else has done, but it will be different. And maybe it will touch somebody in a different way. So it’s not a competition. It’s a matter of expressing my feelings, which is what is so gratifying about using scripture as a starting point for a painting.”

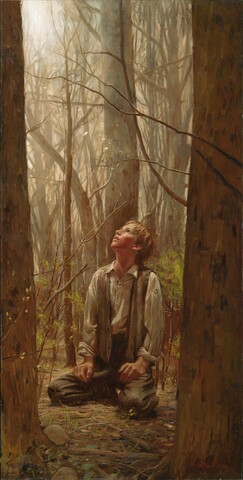

Walter’s paintings have portrayed the scriptures in ways that had previously never been done before. According to curators, his depiction of the First Vision was particularly revolutionary.

Typically, artists depicted Joseph Smith as a well-built man in his Sunday best to make him appear more noble, following a tradition that dates back to the 19th century. Walter, on the other hand, painted Joseph as a 14-year-old boy in everyday clothes in a setting of early spring rather than late summer. The difference in that narrative can mean everything.

“When I tell my children [and grandchildren] the story of the First Vision, I emphasize that he was just a young boy and that great things can happen even to young people,” Oman says. “Great spiritual things of great historical importance can happen even for a very young fellow. And so it reinforces that they themselves are not too young to have significant spiritual experiences, and that they should live accordingly. And Walter’s painting communicates all of this.”

“The Message of the Painting”

Whether he’s painting Joseph Smith, a scene in the Book of Mormon, or the Savior himself, Walter keeps in mind some key points when deciding what to paint. A primary consideration is if it will make an interesting visual composition, and he prefers when a painting can have multiple interpretations.

“Something that I like very much about what I do is I can have this connection with people all over the world without me being there. So the viewer is having some kind of interaction with a piece where I’m long gone, and [there’s] distance and time, but it’s still creating a dialogue with somebody and having hopefully a good effect on somebody,” Walter says.

That conversation with the viewer is often based on the message that inspires Walter’s work. Therefore, the focus of his paintings is not always what one would expect. For instance, in He Anointed the Eyes of the Blind Man, Walter does not make the Savior the center of the painting but instead highlights His actions.

“I wanted the subject to be what Jesus was doing and His ability to heal. So I decided to make the focal point of the painting His hands, and then I even cropped His head so [it] is going out of the picture—it’s not entirely in the picture and [is] way up in the top corner. So I like doing that sort of thing, where [I] divert the attention from what Jesus looks like to what He’s doing.”

For similar reasons, Walter doesn’t deviate much from the traditional depiction of Christ as a man with long, slightly wavy hair, a short-cropped beard and mustache, and a long, oval face.

“You think, ‘Well, maybe I should break loose from that,’ because we don’t really know what He looks like. But I had always steered away from doing that because I don’t want that to be the subject of somebody saying, ‘Well, what’s going on here? Who’s that?’ I want people to be able to get over the fact that this is Jesus and get on to the message of the painting.”

This doesn’t prevent Walter from thinking outside the box when he paints Christ. In Jehovah Creates the Earth, commissioned for an exhibition on the life of Christ, Walter paints a scene of the Savior surrounded by stars while forming a large, glowing, orange-and-red sphere with spots of blue. Oman says Walter was the first one to come to mind for the project.

“I said, ‘I want something more in the league of Michelangelo and the Sistine ceiling. I want something with energy and power in it.’ And that’s exactly what he delivered. And I think he created, by far, the finest depiction of the Lord creating the earth that I have ever seen by any Latter-day Saint artist. It is a stunning masterpiece. And man, does it have energy and power in it. And if you know the Sistine ceiling and you look at this piece, you can see elements of a shared vision between him and Michelangelo.”

Hoping to convey what words cannot, Walter utilizes composition before facial features or costumes to create feelings of tension or peace in his works. This is apparent in paintings like the biblical story of the ten virgins, where the women who did not have enough oil in their lamps seem to be on lower ground and shrouded in darkness, while those with oil in their lamps are glowing in light.

“The indecision, the struggle—Which side of this would I be on? When the time comes, am I going to be ready?—doesn’t just come through by painting a picture of 10 young women in biblical dress with lamps,” Walter says. “It has to do with the composition and how the poses create linear patterns that bounce you back and forth across the image that hopefully subconsciously give you that feeling, Am I over here? Am I like that person?”

Husband, Father, and Painter

While painting is Walter’s passion, his family has always come first in his life. He and his wife were quick to expose their four young boys to art, and as a family the have often attended museums together.

“He’s an amazing husband. He’s an amazing father. When our boys were young, he always had someone on his lap—a child, or a baby—and could paint,” Linda says. “He’s intense with his art and he gets in the zone and he can focus, but it never took away from his time or attention from the children.”

Walter has also involved his family in his paintings. His son Peter laughs that they have worn many an outfit from his dad’s costume chest when a model was needed: robes, smocks, and even an antique sword have all been employed in the past. And while his father’s dedication to his craft is clear, Peter says he and his brothers always knew they were more important to him.

“Growing up in the home, you knew he loved to [paint], but the painting never took a priority over any of us. Not for a second. If we were going to interrupt him, which we did constantly, there was never a ‘Oh, just a minute, hold on.’ He would drop what he was doing immediately. . . . That’s something that has always impressed me,” he says.

Walter is equally dedicated to the gospel and was recently released as bishop in a young single adult ward. Over the years, he’s seen his paintings on the covers of Church magazines or heard that someone saw one of his originals in a temple, and it’s always a pleasant surprise to learn how his work is being used. Linda says she can’t imagine her husband doing anything but the craft he loves so much.

“Every minute that he can have a brush in his hand painting, that’s where you will find him. And he absolutely loves it,” she says. “He was just born to paint because he’s so passionate about it. . . . He told me he could live in a tent as long as he could paint. And that would make him happy.”

The Creator

Walter and Linda currently live in New York City, where he finds himself constantly inspired by his surroundings and the people who live there. He paints whatever he feels most called to in the moment, but, regardless of the project, the creative process is rarely a seamless experience.

“I always start out because I’m excited,” he says. “But it’s inevitable that at some point, I get to the point where it just seems like a disaster and not worth wasting my time on. Very seldom do I start a painting and I can maintain that confidence all the way through, knowing that it’s going to be good. And then maybe those are the times where actually I’ve fooled myself and I realize, ‘Well, it’s not as good as I thought it was.’”

But the struggle is important, and he doesn’t mind showing that in his work, constantly making decisions about color, shape, and position while working. Sometimes, his changes to pieces are subtle; at other times, dramatic. Even if he spends hundreds of hours on a single painting, he doesn’t sell a piece unless he loves it, sometimes waiting for years until it comes together the way he’s envisioned.

There’s something about the creative process that keeps Walter coming back to the canvas again and again and again. It’s not that he’s seeking perfection. It’s not that he’s looking for praise. He simply loves bringing brush and color and inspiration and imagination together, creating what wasn’t there before.

“We are commanded to live Christlike lives,” he says. “He’s [the] Creator. That’s what He does. I interpret that as if we’re to become like God, we should be creative people ourselves. . . . We’re taught that we can be co-creators and we can become like God. . . . I think that we should think about our creative side and use it, and not just think about following in lockstep. Maybe thinking a little differently than other people is a good thing.”