As Latter-day Saints prepare to celebrate the 175th anniversary of Pioneer Day on July 24th this year, LDS Living recognizes that in addition to the sacrifices of the early pioneers, there are many modern-day pioneers across the globe who have built the Church in their nations or in their families. In this new series of articles, we wish to recognize these present-day pioneers and remember all who have helped make The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints what it is today.

When Mormon pioneers arrived at the edge of the Salt Lake Valley, their leader, Brigham Young said, “This is the place.” I wonder how the pioneers felt? Were they relieved? Dismayed? Perhaps still deep in grief for the homes and lives they’d been driven from?

On my father’s side, my Japanese side, our first Utah settlers came in 1945. I’ve often wondered what my grandmother felt when she first arrived in the quiet dryness of rural central Utah. Did she, like Brigham, think, “This is the place”? Or was she perhaps afraid?

Like the Mormon pioneers, my family had been driven from their homes. After Pearl Harbor was bombed, all Japanese Americans on the West Coast—120,000 in total—were imprisoned without trial. Many had a week or less to pack and sell their things. Homes, farms, automobiles, and everything else, were lost or sold for pennies on the dollar. Career paths were interrupted, romances stalled, and basic dignities stripped. In many cases, fathers were separated from their families.

At the time, 93% of Americans polled1 favored sending Japanese first-generation immigrants to these camps. This group—the issei as they were called—included my great-grandfather Sashichi, who had come to the United States forty-four years earlier. As was the story for so many immigrants, he came when America needed help breaking the land, establishing infrastructure, and creating an economy. The US sent out advertisements calling for men from Asian countries to help.

But as is also too often the case in our history, Americans were surprised when these laborers refused to be disposed of after the job was done. The Japanese had built lives here, dared to have their own families, and dreamed of their own businesses and farms. Suddenly, they were competition. Those who opposed the Japanese formed lobbies and laws banning any more Japanese from immigrating, denying them citizenship, and prohibiting them from owning land. When Pearl Harbor was bombed, these groups lobbied for Japanese Americans to be forcibly removed.

My grandparents were second generation—referred to as the nisei. Born in America, they spoke English better than Japanese, knew the culture of this country better than the culture of their ancestry, and when asked by their parents about returning to Japan, they begged to stay in their country, the United States. My grandfather, Charles Inouye, graduated as valedictorian of his class, my grandmother, Bessie Murakami, as salutatorian of hers. With major sacrifices made by his parents and sisters, Charles completed a college degree at Stanford. He was deciding between further education to become a lawyer or an accountant when the war broke out. Bessie worked in a dentist’s office. Having worked on her parents’ farm since childhood, she was determined not to marry a farmer.

Then Japanese airplanes bombed Pearl Harbor, and both were suddenly torn from their lives. They were pinned with numbered tags, funneled through chutes like livestock, and assigned to “temporary assembly centers.” These centers turned out to be racetracks where they were forced to live in horse stalls whitewashed to cover the manure still caked to the walls.

Months later, they were taken to a more permanent prison camp at Heart Mountain, Wyoming. My grandmother recalled that it was terribly cold, that the wind “just blew and blew,” and that for miles there was “nothing, just sagebrush.” When they’d walk outside, they’d come back with a layer of dust covering their faces. The toilets were unfinished and had no partitions for privacy. The food made thousands sick. Guards manned towers and pointed guns at them. The tiny barracks they were given were covered only in tar paper, which they stuffed with whatever fabric or paper they could find to keep the cold out.

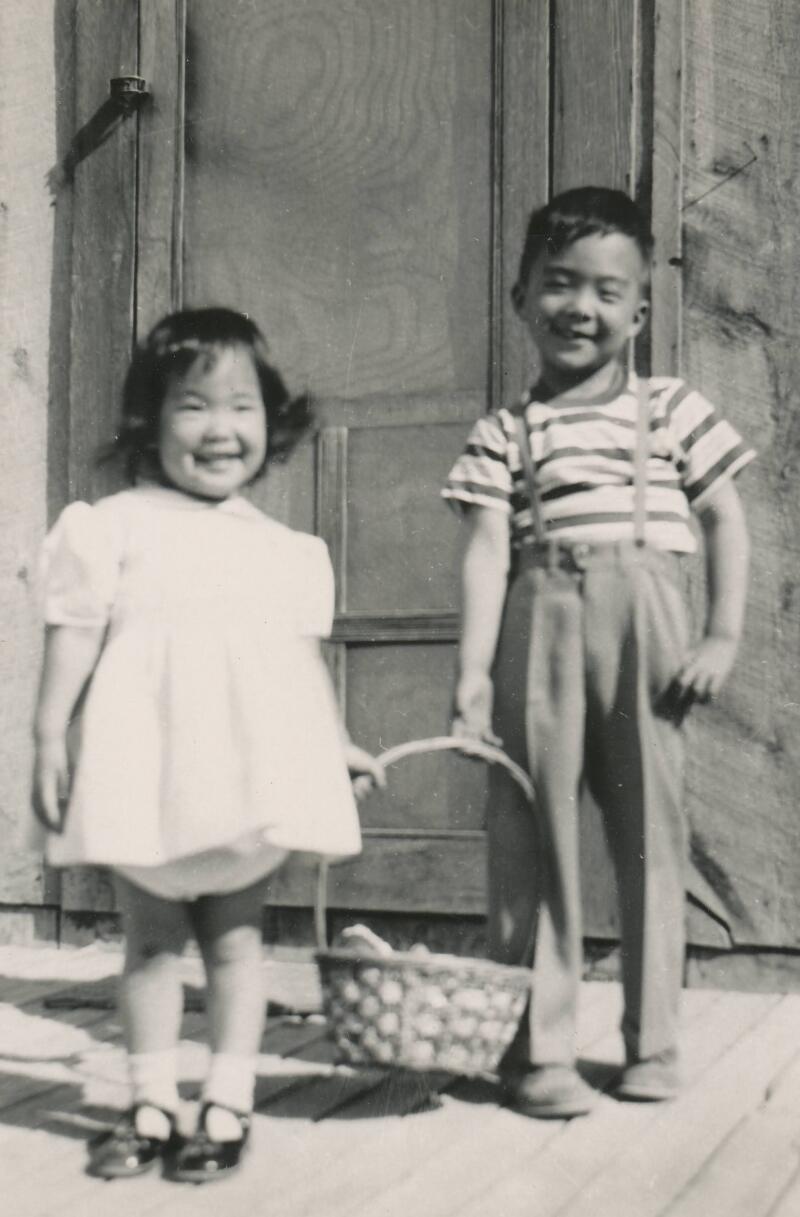

This is where Charles and Bessie met, dated by walking in large circles around the camp, and married. My father, Dillon, was born in the camp hospital, premature and in need of better equipment and care. But he was lucky, unlike other infants who didn’t get the care they needed, and he survived.

Then the war ended, and the United States suddenly saw the cost of imprisoning these “inmates” as an unwanted expense. The government shut the camps down and expelled those who’d lived there, giving each only $25 and a bus ticket to start their new lives. In many cases, Japanese Americans again had only a week to find new lodgings. This was made even more difficult when ordinances and prohibitions sprung up in much of the West Coast, banning Japanese Americans from returning to their hometowns. My grandparents were among those who couldn’t return to their homes on the coast. But my grandfather’s brother-in-law, Henry Mitarai, found farming work in central Utah, and my grandparents followed him.

What did Bessie feel when she first stepped out and surveyed Sigurd, Utah, this foreign place she was supposed to call home? I never asked, and now it’s too late. But I’ve seen the weight of its silence bring other people to tears. My grandfather, I’ve been told, practically and perhaps a little cynically said, “Well, racism can exist anywhere. This is as good a place to try as any.” He and Henry bought tar paper barracks from another prison camp in Utah and trucked them to their new town. My grandparents would live in their barracks for the next decade.

On the West Coast, they had lived in neighborhoods of Japanese American friends, many of whom had shared their Buddhist beliefs. Then in the camp, they’d been surrounded by people with whom they shared both their ethnicity and culture. But in Sigurd, their new neighbors were almost all White and Mormon. Given all they’d been through, my family wondered—and feared—how they’d be received.

My aunt Jeannette Mitarai (now Misaka) was 13 at the time. She was scared to start school, afraid of what the kids would think. Hearing this, the principal, a man named Alma Edwards, introduced her at a schoolwide assembly. He said, “Students, we have a new student amongst us. She is an American just like you. If you have a problem with that, you come see me.”

Imagine what that would have felt like to a family whose patriotism had been so publicly questioned, who had been forced to walk past their neighbors with numbered tags on their coats, who had been treated as subhuman and kept in horse stalls. Even in her nineties, my aunt speaks about Mr. Edwards with gratitude. His words “opened the door,” she says.

He was the first of many to treat the family with kindness. Bessie forever remembered the kindness of a small cluster of Latter-day Saint women who almost immediately brought the family bread. These same women eventually invited Bessie and Henry’s wife, Helen, into their homes, teaching them how to can peaches and make soap. Their husbands shared tips, equipment, and irrigation with Charles and Henry, who were new to farming in such a dry climate. And when my grandparents’ 6-year-old daughter, Charlotte, battled leukemia, church members gave her blessings and shared their religious beliefs about life after death and eternal families. When Charlotte died, Bessie especially drew on these teachings for comfort.

There were others who didn’t treat the family well. There were those who took advantage of them in business dealings, kids who were bullies, and parents who didn’t want their children to associate with Japanese Americans. My grandfather never realized his goal of being a lawyer or accountant; enough residual racism existed, and his career path had been permanently disrupted. My grandmother ended up being married to a farmer after all.

But over decades, my family became part of the community in which they’d planted themselves, and they served the community in return. They worked with the neighboring farmers to save each other’s farms during a historic flooding. Henry found 180 wells for farms around central Utah. And Henry and Charles served in community organizations like the Rotary Club and Lion’s Club.

My grandparents stayed in central Utah until the end of their lives, eventually settling in a town called Gunnison. Their son Dwight became a doctor for the area. Other members of the family became teachers and needed professionals. They volunteered in civic causes, first throughout Utah, then the United States.

Some—including Dillon, Henry, Helen, Charles, and Bessie—eventually joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. There were as many members of the family who didn’t join as did.

But here’s the thing: Whether or not they joined wasn’t—and shouldn’t be—the point. Those who gave the family a community in which to belong were reaching out in kindness, esteeming others as themselves. It’s not only the decent way to treat fellow human beings, but it’s also what Christ has asked us to do. Maybe those Latter-day Saints in central Utah remembered the time when as a people, they too had been driven out and ostracized. As the scripture goes, “Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me.”2

Our family didn’t come to Utah with the Mormon pioneers, and I doubt my grandmother immediately thought, “This is the place,” when she got here. But they were pioneers of another sort.

They made a home here. They raised their children here. They served and were served by their community. And they came to fiercely love the people and this beautiful place, with its spareness and space and sometimes silence.

Notes

1. See https://exhibitions.ushmm.org/americans-and-the-holocaust/main/japanese-american-internment.

2. See Matthew 25:40.