Which New Testament ghost casts more gloom into the hearts of believing women than any other? More feelings of discouragement, failure, and the impossibility of doing right? Martha, whose sister is Mary, whose brother is Lazarus, is that ghost. But it’s not Martha herself who is responsible; it’s the shadow of her we have created through our careless conversations about her.

We remember Martha for one thing: She complained to Jesus that Mary wasn’t helping her make dinner. We don’t remember her generosity in spontaneously inviting Jesus and His disciples into her home, nor her display of faith after her brother died. Jesus’s response to Martha’s complaint gave Christians thereafter, including us, a basis for seeing housework as inferior to study—the life of the mind re-emphasized as superior to that of the body. By extension, those who spent a good part of their lives in housework learned to see their contributions as less-than—and believed that if they complained about unjust divisions of labor, that would be further evidence of their inferiority.

I don’t think this interpretive legacy is what Jesus wanted because it is inconsistent with His other teachings and behavior. Jesus Himself did housework. The times of Jesus’s life that we know the most about are His thirties, and the last few years of His life. He doesn’t seem to have had a home during those years, but even so He taught us some things about service and housework. He took on the responsibility for thinking ahead about meals—advising His disciples on where to go and what to do about food (at the final Passover, for example). He Himself also cooked, preparing fish on the beach for His disciples. Sometimes, He performed miracles to make sure that people were made comfortable and fed.

In the first miracle we know about, He served people at a wedding—turning water into wine at Cana. Two and a half years later, He transformed a few pieces of coarse bread and dried fish into enough to feed thousands. At the Last Supper, He not only prayed over the bread but broke it Himself and served it to people. He washed His disciples’ feet—a symbolic act that was also housework. Washing the feet of guests was one of the least regarded acts of housework Jesus could have chosen to undertake. If a household had servants or slaves, they would be the ones to do any foot washing. Jesus’s act of service shows that no housework, no act of care, is beneath God. He showed us that the planning and work of housework are well worth our energy because He performed them even when He didn’t have a house. Because housework is an essential means of serving others, I believe He will help us to do it.

Because housework is an essential means of serving others, I believe He will help us to do it.

With Jesus’s actions in mind, I hereby propose a theology of housework. Theology is the study of religious faith and practice, and housework can be a religious practice, something that can bring us closer to God and other people. Like many things that bring us closer to God, housework is a crucible—a container that holds great heat to refine metal. Housework can cause exploitation and, in response, resentment. It is a place that can consume us, either because we spend too much time on it or because we ignore it and the consequences of that neglect eat away at us.

Yet housework is also an opportunity to feel grateful for temporal blessings and to do the work of Jesus, which is to serve others. Both things are true about the crucible of housework: it can make us feel inadequate, and it can be an opportunity to understand God more fully, increasing our sense of gratitude and receiving answers to pleas for help.

Forgiveness

Housework functions most clearly as a spiritual crucible in the regular opportunities it brings us to forgive. Most of us end up with family members who have different conceptions of what “completed housework” means. My friend Emilee says that many things she finds essential just don’t make sense to her family. She can’t get them to understand the purpose of top sheets, for example. Recently, when her son obediently made his bed, he carefully laid the top sheet over the spread. Housework means negotiating with each other, with time constraints, with the voices in our heads. Negotiation often skirts the edge of conflict, and it creates frequent moments that call for forgiveness.

Two things are true with forgiveness when it comes to housework: we can’t resign ourselves to unremitting victimhood, and we also need to forgive. Both actions are crucial to our well-being: the universal commandment to forgive does not mean accepting exploitative relationships, where the housework is divided so unequally that one person’s development or well-being is compromised. In this, we have Jesus as our example.

Two things are true with forgiveness when it comes to housework: we can’t resign ourselves to unremitting victimhood, and we also need to forgive.

When people behaved badly in their relationships, Jesus told them to stop. He didn’t hope things would automatically change on their own; he communicated his understanding of right and wrong. Often, he did so subtly. When the disciples were arguing about which one of them was greatest, he responded by undoing the category of “greatest” and, as I understand it, taught them to cut through considerations of status. If we take Jesus as our guide in negotiating housework, we can feel confident in communicating what we understand to be fair and right within our own relationships, especially when others may, like the disciples, need to reconsider inherited assumptions of gender, age, or class status. At the same time, Jesus’s example guides us toward a gentle approach in these conversations around housework. We aim to teach and persuade rather than coerce and shame.

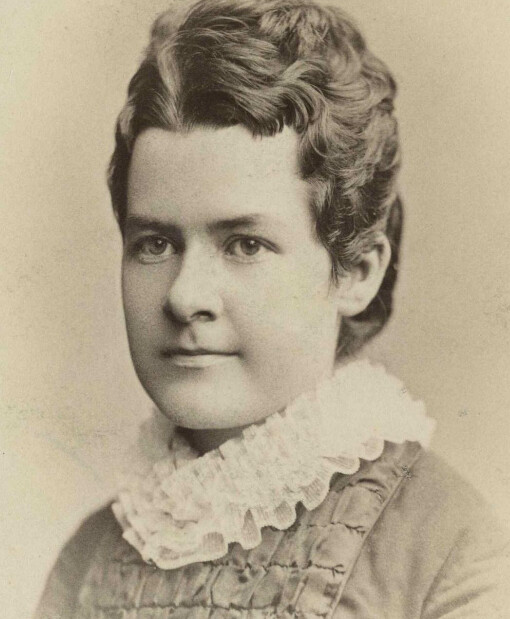

While housework is a commonplace part of life, long-term overwork can do serious harm to a person’s potential to contribute to the world and experience joy in life. Martha Hughes Cannon (1857–1932) was an early Latter-day Saint suffragist, state senator, and physician. She wrote to her friend Barbara Replogle in 1884, “’Tis not the bringing of noble spirits into the world … that dwarfs talent, and retards her intellectual advancement but it is the multiplicity of household drudgery… and the conformity to the vile customs of modern society. Barbara even if we have to be poor let us … strive to become women of intellect, and endeavor to do some little good while we live in this protracted gleam called life.”

Cannon’s position was that housework endangered the pursuit of excellence. She was right. Today, I could fill my life with so much housework that there would be no time left to write or study or play. I can imagine that housekeeping in Utah during the nineteenth century could become all-consuming. In fact, Brigham Young and Mary Isabella Horne, a prominent Relief Society leader and women’s suffragist, had begun late in 1869 a retrenchment program that encouraged women to dress simply and to prepare uncomplicated meals. One of their stated goals was to free women’s time from needless domestic labor, so more of it could be spent studying the gospel and in other “edifying” civic pursuits. Their message may have been that housework was a necessary evil, not edifying in and of itself. But maybe they only meant to safeguard against too much housework. As Cannon recognized, the “multiplicity of household drudgery” can stunt a person’s talents and intellect or dampen her joy in “this protracted gleam called life.” Such a situation might call for serious and direct efforts to rebalance housework in a relationship.

Still, the constant repetition of housework means that sometimes our attempts to negotiate housework won’t be resolved perfectly. We will have to forgive, again and again. If that forgiveness is offered unwillingly, we can find ourselves holding on to a grudge. A revelation on mercy and forgiveness given to Joseph Smith during a contentious period among Church members reads, “I, the Lord, will forgive whom I will forgive, but of you, it is required to forgive all men.” It may be hard to accept that the Lord wants us to forgive everyone, though there is comfort in knowing that he will judge some of them. But if that is the case, why not allow us to hold a grudge? Are we justified in begrudging housework?

To answer that question, we need to think about what comes from holding a grudge: we might experience a feeling of superiority or a feeling of restoring balance in the universe. The feeling of superiority is not conducive to growing, loving relationships, so we can discard that as a justification for resentment. A feeling of restoring balance in the universe, on the other hand, is good. But the reality is that we don’t actually achieve balance through exercising our own judgments against people, because our vision is narrow and flawed. I may feel justified in my angry grudge against my partner over laundry or dishes, but my perspective is painfully limited in comparison to God’s understanding of each of us.

Really, I think the only way to trust that there is balance in the universe—even when it comes to something as ordinary as housework—is to let God do the judging. If this is the case, then the scripture is true—let God forgive whom He wants, and let us forgive everyone. Unlike the work of balancing the cosmic scales of the universe, which lies outside our ability to understand or achieve, striving for humility and charity does lie within our compass. Trying to forgive, with humility and love, is a more reliable path to peace—in housework and in life.

Read more from Kate Holbrook about the crucible of housework and other gospel topics in the book below.

Both Things Are True

Both Things Are True is a guided walk through six sets of tensions that disciples must navigate in their practical efforts to become like Christ. Author Kate Holbrook draws on her lifetime of expertise as a historian of Latter-day Saint women's history to examine the "contraries," the fruitful tensions that have stretched Saints present and past, including the true Church, revelation, housework, forgiveness and accountability, and legacy. While the book is richly illustrated with personal and historical examples, its ideas are expressed in the simple, gentle manner that is Kate's trademark. Both Things Are True is remarkable in its ability to reach readers of every walk of life. Available at Deseret Book and deseretbook.com.