This article was published in the July/August 2009 issue of LDS Living in honor the the 80th anniversary of Music and the Spoken Word. We are publishing it again to celebrate the program's 90th anniversary and have updated the article to include current information.

The smooth, baritone voice of Lloyd Newell warms the air in the Salt Lake Tabernacle, as the historic organ tunes up to “Gently Raise the Joyful Strain.” These well-known words open Sunday morning: “From historic Temple Square in Salt Lake City, we welcome you to Music and the Spoken Word, with the Tabernacle Choir and Orchestra at Temple Square.” This signals the start of one of the most beloved programs of all time—the world’s longest running continuous network broadcast.

In 1929, Music and the Spoken Word (MSW) began greeting listeners weekly in homes across the United States. Now it reaches people across the world. Broadcast to more than 20 countries (including Austria, Australia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Hungary, Lithuania, Philippines, South Africa, and Switzerland), it has made a name for the Tabernacle Choir and the Church in places we once only dreamed of reaching.

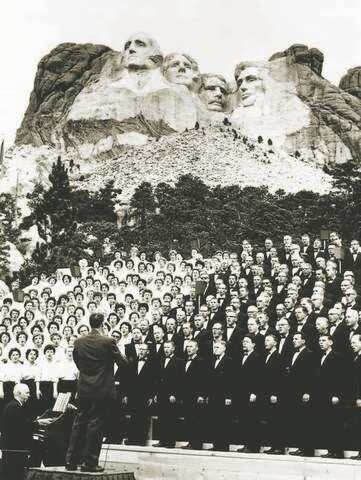

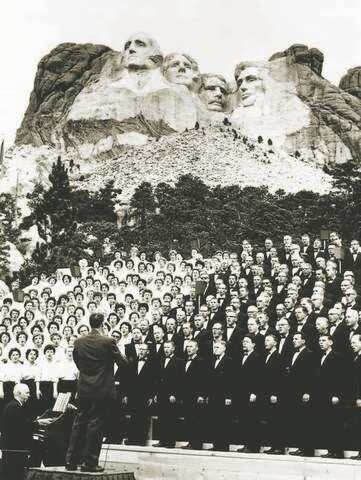

Its scope is astronomical. On any given Sunday, more than 2,000 radio, television, and cable stations pick up the program. It has been filmed on the steps of the US Capitol Building, in the Royal Albert Hall in London, and from Jerusalem. On its 25th anniversary, Life magazine called it a “national institution to be proud of.” And now, it’s been on air for 90 years. But it hasn’t always taken place on such a grand scale.

In the Beginning

If you had followed the wire running one block from Salt Lake City’s KZN radio station to the Tabernacle on July 15, 1929, the day of the first broadcast that would be known as Music and the Spoken Word, you would have witnessed a scene most unlike today’s MSW.

With the only microphone from KZN hanging from the ceiling, 19-year-old Ted Kimball, son of Tabernacle organist Edward P. Kimball, climbed a 15-foot ladder to announce the program.

He stayed on the ladder throughout the 30-minute broadcast, pointing the microphone toward each section of the choir in turn as they sang their parts. Sound pollution was rampant in that first broadcast—listeners could hear the shuffling of feet, the tapping of the conductor’s baton, and a hum from the radio line.

Even with the rough patches of the debut production, M.H. Aylsworth—president of NBC (which transmitted the program for the first few years)—sent a telegram with his congratulations: “Your wonderful Tabernacle program is making great impression in New York. Have heard from leading ministers. All impressed by the program. Eagerly awaiting your next.”

Soon the program saw more stability. After three years of airing with NBC at varying weekdays and times, MSW switched to CBS and a weekly slot on Sunday morning. But the greatest stability came when the program settled with an official announcer in 1930—Richard L. Evans, who announced the program from age 24 until his death at 65 and who made MSW what it is today.

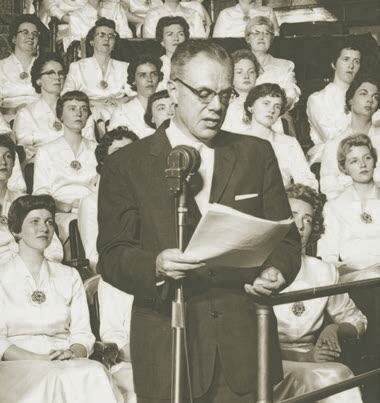

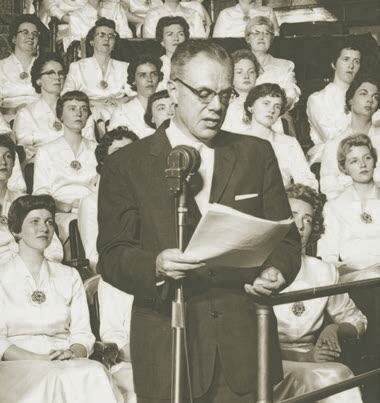

Richard L. Evans

Originally, the place of the voice for MSW was to announce the beginning and end of the program, as well as the musical numbers in between. But as Evans settled into the role, he began relating the titles of the songs to points of philosophy or timeless morals. These “sermonettes,” as they came to be called, were nondenominational (in keeping with the public service nature of the program) and never detracted from the choir, but they added a greater inspirational dimension to the program, which listeners loved.

“He’s really the one who shaped the program we know today. I still use his words at the beginning and end of the broadcast,” says Lloyd Newell, current voice for MSW.

Evans of course announced the program, but he also wrote all the sermonettes and produced the program. In addition to this, he also served as editor of the Improvement Era, president of Rotary International between 1966 and 1967, and as an apostle in the Quorum of the Twelve for 18 years. Then, after over four decades of service, the years of hard work unexpectedly ended when Evans contracted a viral infection and died in 1971. Listeners around the world mourned his loss.

The Era of Mass Media

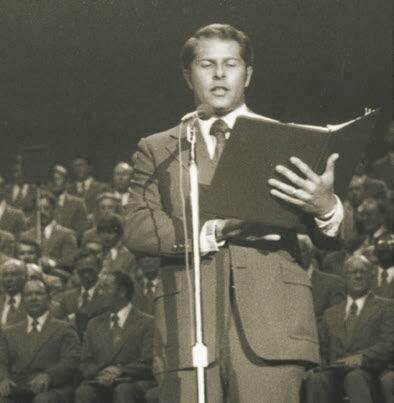

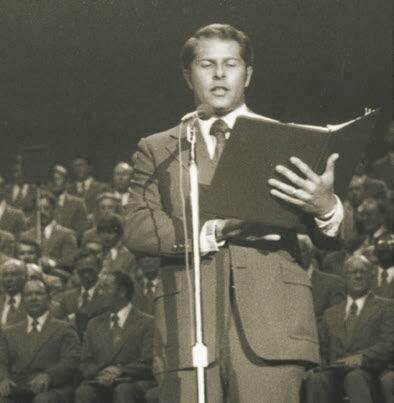

Spencer Kinard

It took about a year to find a replacement for Evans, but ultimately J. Spencer Kinard, a news reporter for KSL, took up the spot. With big shoes to fill, Kinard was soon comforted with counsel from Elder Gordon B. Hinckley that he didn’t need to recreate the program—he just needed to “pick up where [Evans] left off.”

Kinard served as the voice and one of the writers for 18 years, until Lloyd Newell took over in 1990. Many people believe Newell’s work with MSW is his job, but Newell serves as the announcer on a voluntary basis (though he is paid for writing and coordinating the messages). It’s a lot of work, but that’s not his focus.

Lloyd Newell

When President Gordon B. Hinckley called me in 1990, he said, “You’ll do it till further notice.” He also told me that “this calling will change your life.” He was right, and in a way I certainly did not comprehend at the time. This calling has changed my life and the life of my family for the better.

► You'll also like: Lloyd Newell: The Voice Behind Music & the Spoken Word

"Each week, I am blessed to begin my Sunday with the greatest choir on earth. I’ve traveled with them to Europe, Israel, Canada, and to most parts of the United States. I’ve seen so many choir members come and go over the years, but always there’s that same commitment and consecration to their calling. Along with the Orchestra and Bells on Temple Square, we become like a giant family as we travel and perform together. It is a blessing and privilege to associate with them."

He continues, “When you consider the history of [the program], it’s taken the country through the Great Depression, through world wars, through great national upheaval. And yet—steady, strong, and inspiring—there is the choir and its broadcast.”

Mack Wilberg, director of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, even uses the same formula that’s been used for years: timeless songs that appeal to a wide audience, that instill hope, and that inspire. And he’s not about to change it anytime soon.

“You don’t want to try to fix something that’s not broken,” says Wilberg.

For 90 years, the essence of the program has remained consistent. However, the production has changed dramatically. And though you wouldn’t know it in looking at the program, with its simplicity and beauty, quite an endeavor takes place behind the scenes to create this treasure.

Lights, Camera, Action

Ed Payne, producer of MSW, is a very busy man. Every week he supervises a crew of 30 to get the show on the air; when the show is in the Conference Center (or “supernacle,” as it’s called by insiders) around general conference, that number grows to meet the size of the venue. As producer for the Audiovisual Department of the Church, Payne also produces general conference and special programs the choir does.

Most of the shows he produces are done live, which hardly anyone does for a feature presentation. “I can’t make a mistake,” he admits.

Ryan Murphy, associate music director of the choir, adds, "Recording an album is not unlike what we do every Sunday morning. Music and the Spoken Word is technically a recording session—except Sunday morning we can't do it over."

From beginning to end, here’s how the machine works: A month or two out, the creative directors, Mack Wilberg, and writing director Lloyd Newell meet to plan the next couple months of shows. If something like Abraham Lincoln’s birthday is coming up, they might try to incorporate his favorite song; if the choir is preparing some pieces for a recording, they might perform those as practice. For the most part, Wilberg outlines the program.

“We don’t come up with anything the choir does. This is their program; they would do a live event even if we weren’t there to run cameras,” says Payne. His crew is there, he says, to make sure the program is as beautiful as the choir’s sound—“to make sure that the show is flawless.”

Fast forward to the week before the program, on Tuesday: in a small room below the Tabernacle, the producers, choir directors, sound crew, orchestra manager, general manager, staging coordinator, and even the floral crew are gathered for the weekly production meeting. Now they actually talk strategy for making the program flawless.

They discuss the week’s specific positioning for cameras and equipment, the special needs for each song (is the piano tuned for the eighth song’s solo?)—even the positioning of the conductor. It gives you an appreciation for how well-trained everyone must be—that they can think of such detail and deal with everything on such a short (even last-minute) timeline.

“It’s nice to have a crew that knows what they’re doing,” says Payne. “They just need to know what the specific details are and they do their job.”

After a two-hour choir rehearsal on Thursday, the next big day is Sunday—showtime. While Newell is in one of the control rooms checking the continuity of his script, the choir is practicing the show’s songs together for only the second time. By 8:30 a.m., everyone is ready to run through the show as if it’s live.

After the broadcast is over, everyone takes a moment to share a “good job” or a “well done,” and then it’s immediately on to next week’s program. “Like we affectionately say, it’s a hungry beast that has to be fed every week,” says Newell. “It’s not something that you finish and then you’re done for a couple months—it never stops.”

With all the demands of the program, you have to wonder: When does enjoying the program come in for these people? Is it always technical?

“We’re here to uplift, to inspire, to console, and to have people feel a spirit of music that we honestly feel is like unto a prayer,” Payne says as he reflects on this monumental task. “But there’s nothing more incredible—from having a rough week myself—than when they finally go on air and I can’t fix the show anymore. I can sit back and I can listen to the choir live, and feel what we want everybody else in the world to feel—you know, when the hairs raise up on the back of your neck.” Then, almost as if he’s telling himself, he breathes, “Man, it’s worth it.”

The Star of the Show

Payne’s reaction to the music of the show is not unusual; in fact, it’s exactly as all the producers, technicians, and directors would have it. After all, MSW may have many aspects not related to music, but they all exist for one purpose: to enhance the choir.

And yet, even as the focus, the choir has perhaps the least time of anyone to prepare for the broadcast—two hours every Thursday and about two hours on Sunday, with an additional two hours on Tuesday about every fourth week. Many travel long distances—up to a few hours—in order to get to Salt Lake City for practice. In addition, choir members must also prepare for tours, CD recordings, and special performances. Yet even with very little time together, this unpaid choir manages to retain prestige as one of the best choral ensembles in the world and, more importantly, continues to touch people’s hearts.

“It’s a testament to each choir member’s individual talent and abilities. Then when you put all of that energy and talent together, it seems to work week in and week out,” says director Mack Wilberg.

► You'll also like: How the Tabernacle Choir's Arrangement of "Brightly Beams" Helped One Man See Past Theological Differences

The choir also provides the desired spirit for the program. Because the program is a public service and stations run it for free, endorsement of religion is not allowed.

"The choir’s music is the star of the show," Newell says, "but it’s more than just music. And that’s why people feel something when the choir performs. It’s powerful and it’s deep—and you and I know what that is.”

Deep Impact

Music and the Spoken Word has indeed touched many over the years. While many inside the Church can relate their own traditions to the program, even the likes of Walter Cronkite and Oprah Winfrey grew up listening to and loving the choir.

“Occasionally [Latter-day Saints] think it’s this little program we do,” says Newell. “But most of the letters I get are from [nonmember] people that love the choir and love the program.”

That’s saying something. The letters Newell receives fill several Rubbermaid bins in his home. These letters, which are also sent to Wilberg and Payne, come from all over the world. Sometimes they include stories. Sometimes they include donations. Sometimes they come addressed to The Minister of the Church of the Crossroads of the West. Everyone who receives the letters describes his desires for the viewers in the same terms: hope, inspiration, beauty, consolation. And that’s what the letters communicate.

On a past anniversary,* Ann Brady of Utica, New York, wrote of the inspiration MSW gave her to join the Church. “Of all the religious programs on the air, [Music and the Spoken Word] gave the most inspiration; it gave me something that motivated me to do good and be the best that I could be for the entire week. . . . I started to read all the books in our library about the Mormons. The more I read, the more I knew that I wanted to be a Mormon. . . . The program Music and the Spoken Word was the spark that eventually led me to join The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.”

William Pendleton of Renton, Washington, wrote of a humorous experience in which his family’s doctor, Dr. Robert Hoffman, also turned out to be a Church “member,” at least in his own view:

“Upon questioning him, we found out that his claim to being a member was that each Sunday he made it a practice to listen to the Tabernacle Choir broadcast. He stated that the inspirational Music and the Spoken Word was a spiritual experience he looked forward to each week. He said that Richard L. Evans could bring him closer to our Father in Heaven in those few minutes than others could in hours of preaching.”

And one family wrote of a time when MSW gave consolation and hope amid deep despair: “On a quiet September Sunday, my husband and I awoke to discover that our six-week old son had passed away during the night. . . . It became necessary to take the baby to the hospital to have him examined and officially pronounced dead by a physician, so my father drove us there. . . .

“We left with heavy hearts. But as we entered my father’s van, still clutching that lifeless form, the beautiful strains of ‘I Know That My Redeemer Lives,’ sung by your choir, came over the radio. . . . The longer you sang, the more intensely we felt the bitter sorrow replaced with the sweet.

“It is difficult to express our deep gratitude to you all for unknowingly shouldering some of our burden. We felt that you had waited for us to get in the car so you could help us. . . . Please accept our sincere thanks for the great good that you do for all the world.”

“I’ve talked to hundreds of people over the years,” says Newell.

“Especially in these days when we live in perilous times—everything seems to be uncertain. We need inspiration; we need a source of good news and something to lift spirits—that helps people see they can hang in there and carry on. Music and the Spoken Word is something stable; it means peace, security, and strength. It speaks to me of dependability and inspiration—you can count on it.”

Broadcasters, choir members, and technicians may not have known the monolith they created that day when Ted Kimball climbed his 15-foot ladder, but generations are already grateful that they did. May MSW continue to open causeways of hope and inspiration, within the shadows of the everlasting hills, in the 90 years to come.

* Letters excerpted from Music and the Spoken Word: Letters from Listeners after Sixty Years of Broadcasts (Salt Lake City: Mormon Tabernacle Choir, 1989) 6, 29, 37. Used with permission of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

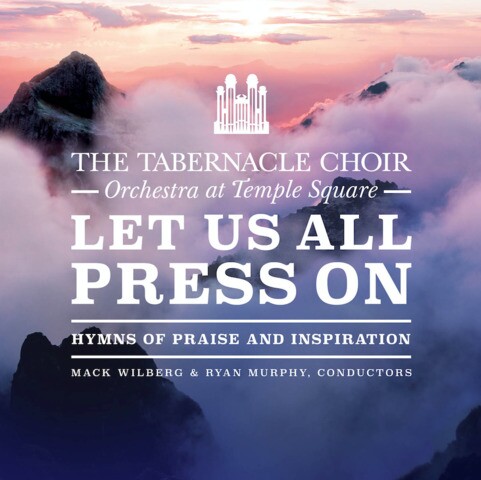

The first hymns album from the Choir in seven years, Let Us All Press On features beloved classics like "All Creatures of Our God and King" and "More Holiness Give Me." The rousing title track, "Let Us All Press On," is a fresh arrangement by Richard Elliott first performed after Russell M. Nelson's historic address by the same name in the spring of 2018.