From praying on an Olympic field to standing up for virtue and modesty, Latter-day Saint Olympians have let their talents and lights shine on the world stage since the beginning of the modern Olympics. Here are just a few of their remarkable stories.

Raising the Bar

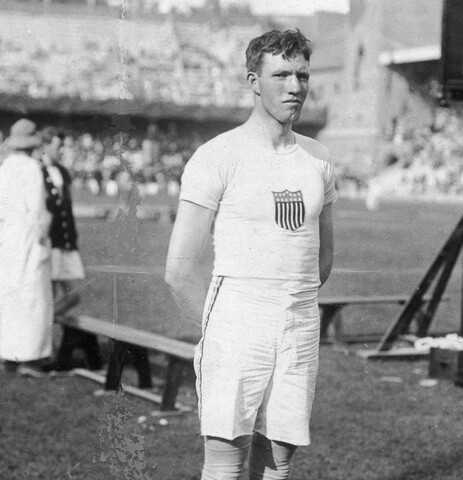

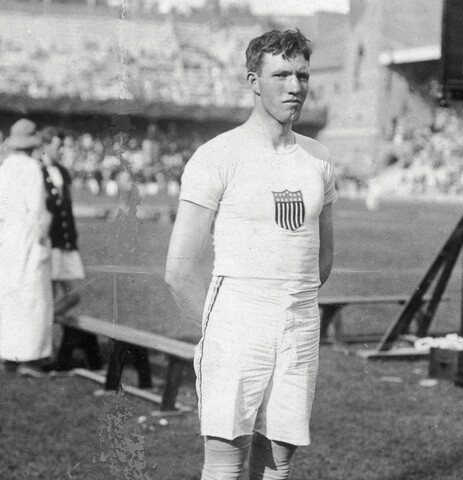

When Eugene L. Roberts told Alma Richards that, with a little training, he could compete in the Olympics, Richards responded, “The what?”

It was just before the 1912 Summer Games and the modern Olympics had been around for only 20 years. A farm boy from Southern Utah, Richards had never heard of the Olympics, let alone thought of competing in them.

Named after two prophets—one from the Book of Mormon and one from modern days—Alma Wilford Richards was the son of pioneer parents. Born in 1890 as the ninth of ten children, Richards dropped out of school for nearly four years as a teenager. By the time he started high school at Murdock Academy, Richards was already 18. That was the year he tried track for the first time, scoring enough points by himself to win the Utah team championship.

The next year, Richards transferred to Brigham Young High School, where his coach, Eugene Roberts, recognized Richards’s potential and began training him as an Olympic high jumper.

Because the Olympics were relatively new, few local businesses were willing to sponsor Richards’s trip to the Olympic trials in Chicago, but Coach Roberts managed to scrape together $150 for the journey.

With a jump of 6 feet 3 inches, Richards clinched the trials. However, because of his relative anonymity, the Olympic selection committee at first dismissed his jump as a fluke. It wasn’t until Amos Alonzo Stagg, a member on the committee who had seen Richards compete in Chicago, assured the committee that there was no doubt Richards could jump that Richards landed a spot on the supplemental Olympic team, earning passage to Stockholm, Sweden.

Competing with 56 other athletes from 20 countries, Richards’s debut on the Olympic field wasn’t very encouraging. His first three rounds, Richards missed twice before finally clearing the bar on his final try.

Richards hung in, however, and when the bar was moved above 6 feet 2 inches, only three athletes cleared the bar: Hans Liesche, a German who had cleared the bar the first time every round; George Horine, a U.S. athlete who held the world record at the time; and Alma Richards.

Then the bar was moved above 6 feet 3 inches. Liesche cleared it on the first jump. Horine missed all three attempts. Richards—well, he managed to clear the bar on his third jump.

The bar was raised another inch. Richards took the field first.

But before jumping, Alma Richards did something unexpected. He walked out on the Olympic field in front of 24,000 people, took off his floppy farmer’s hat, and knelt, saying, “God, give me strength. And if it’s right that I should win, give me the strength to do my best to set a good example all the days of my life.”

With that, Richards leapt, clearing the bar by several inches. Then came Leische. For the first time all day, Leische missed his first attempt, along with the two following.

Alma Richards stood on the Olympic podium that day as King Gustav V hung a gold medal around his neck—the first and only Richards would ever receive.

Upon returning home, Richards made it into Cornell University. In 1913 he became the AAU national high jump champion and in 1915 he became the AAU national decathlon champion. By 1916, Richards was the best high jumper and decathlete the U.S. had to offer, but with the outbreak of World War I, the Games were canceled and he didn’t have a chance to compete again.

Instead, after the war, Richards attended Stanford for graduate school, then the University of Southern California for law school. Despite earning his degree and clearing yet another type of bar, Richards ultimately decided to become a high school science teacher.

Despite the end of his jumping days, Richards continued to raise the bar of his faith and personal standards until his death on April 3, 1963.

Sticking to Standards

In the sports world, Sunday is prime time for competitions. And the Olympics are no exception. With preliminaries, games, competitions, and finals all falling on Sundays, many Latter-day Saints are presented with a very personal choice as they come face-to-face with a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to compete in the pinnacle of sports competitions.

For New Zealander Saints Charmian Purcell and Nonila Wharemate, their decision to not play on Sundays came early in their professional careers. In fact, when prospective recruiters approached Wharemate in college, she made it clear from the outset she would not practice or play on Sundays.

But that decision was put to the test when it endangered Purcell and Wharemate's chances of even making it to the 2008 Olympics. That’s a frightening prospect for two female basketball players who come from a country that rarely competes in Olympic women's basketball.

When asked whether she thought she would ever be competing in the Olympics, Wharemate told UTEP Athletics, “I really didn't think we would. Australia is a basketball superpower, and we normally need to beat them to make it to the Olympics.”

But with Australia winning the world championship in 2006, the Australian team got an automatic bid, meaning New Zealand didn’t have to face them when they competed for, and won, the Oceania placement.

But even after the New Zealand team clinched a spot in the Games, there was no guarantee Latter-day Saints Purcell and Wharemate would make the 12-member roster, especially since both players refused to play on Sundays, putting the team’s coach at the time, Mike McHugh, and the players in a tight spot.

"But we've stuck with our guns,” Purcell told the Deseret News, “and he decided that he'd take both of us.”

Upon hearing that news, Purcell told UTEP Athletics that she was "totally over the moon" about the chance to compete against the best athletes the world has to offer. "There's not a lot of money in this game for women in New Zealand, so all the girls who have made it here have had to work really hard," Purcell says. "It is all worth it when you get to play against the world's best with the name of your country on your uniform and for a team that you love." The only thing that made the experience even sweeter was playing on the same team as her sister—fellow Latter-day Saint and athlete Natalie Purcell.

The New Zealand women's basketball team had a tough road ahead of them, however, and after an initial win against Mali, they lost their next three games. Purcell and Wharemate knew going into their fifth game against the United States that it was their last chance to play in the Olympics. But the game happened to fall on the first day of Sunday play, and Purcell and Wharemate stood by their personal standards unflinchingly.

"I sort of made [no Sunday-play] a criteria from the beginning, right from the recruiting process," Wharemate told the Deseret News. Despite the prospect of glory and the chance to play against U.S. players, even the Olympics couldn’t shake these two women from following the standards they set for themselves early on.

Image of Charmian Purcell (far right) at New Zealand's first Olympic game against Mali. Image from Getty Images.

Dreaming of Something More

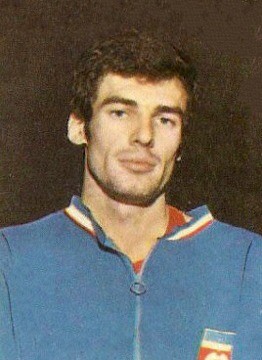

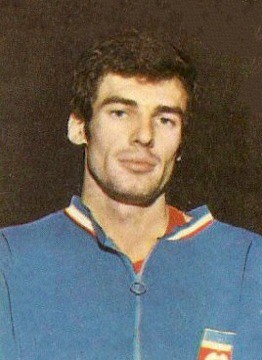

Standing at an incredible 6 feet 11 inches, Krešimir Ćosić was made for basketball. Born in Zadar, Yugoslavia (now Croatia), on November 26, 1948, Ćosić began playing on his national team at 16 and won two world championships and three European championships during his lifetime. He also competed in four Games, earning three Olympic medals.

After helping Yugoslavia secure a silver medal during his first Olympic appearance in 1968, Ćosić was persuaded, with the help of BYU’s head basketball coach, Stan Watts, to attend Brigham Young University.

When he first arrived on BYU’s campus, rimmed with the jagged, imperial Wasatch Mountains, Ćosić experienced a strange case of déjà vu. Having seen those exact mountains in his dreams years earlier, Ćosić felt he was meant to come to Provo.

Later, when his friends explained that dreams can have profound spiritual meaning, Ćosić wanted to know more.

► You'll also like: Convert & Track Star Beats Olympians, Sets Records 6 Months After Mission

That desire led Ćosić to the office of professor Hugh Nibley. Though separated by age, nationality, and 16 inches (Nibley was only 5 feet 7 inches), the two quickly found a strong brotherhood in their faith and desire for gospel learning.

“There are a hundred reasons why I should not join the Church,” Ćosić told Nibley, “and only one reason why I should—because it is true.”

Krešimir Ćosić was baptized by Nibley in November 1971. Because of his height, he used a specially-sewn, extra-long baptismal outfit, and because of his high public profile and unusual political situation, Ćosić was baptized in the basement of the tabernacle on Temple Square.

After his conversion, Ćosić went on to play in the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich, Germany, where he helped his team bring home another silver medal, and in the Montreal 1976 Games. During his final Olympic appearance, in the Moscow 1980 Games, his team at last brought home a gold medal.

Despite the fame and glory brought on by his meteoric career, Ćosić still remained faithful to the beliefs he learned at BYU. At a time when priesthood leaders were not allowed to preach in Yugoslavia, 23-year-old Ćosić became the presiding priesthood holder in his country and helped lay the foundation for the gospel.

Under direction from the Church, he organized the first three branches and performed the first baptisms in Yugoslavia, translated for Thomas S. Monson when he opened Croatia for the preaching of the gospel in 1985, and assisted in the translation of the Book of Mormon, Doctrine and Covenants, Pearl of Great Price, and the temple endowment into Croatian.

At Ćosić's funeral, a prominent Catholic priest, Fra Bonaventura Duda, shared this tribute:

“Our Kreso, ever since I have known him, was a faithful believer, but he did not (merely) speak of it, he performed his faith. . . . He did not only believe in this religion, he truly believed in a personal connection with God. He wholeheartedly tried to practice his faith in real life.”

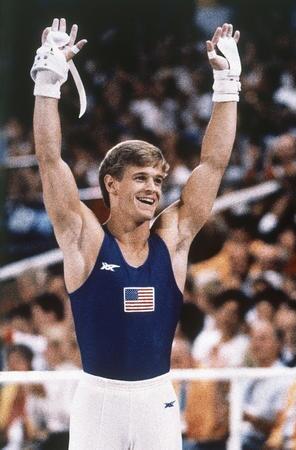

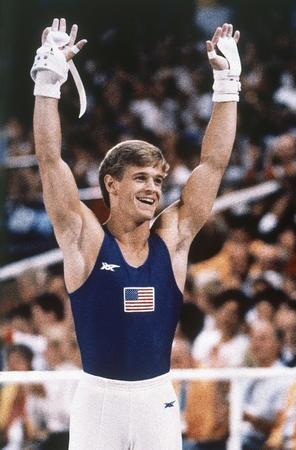

Winning, Losing, and Loving

Peter Vidmar still holds the record as the highest-scoring U.S. male gymnast in Olympic history and is one of only three athletes inducted into the U.S. Olympic Hall of Fame twice. As captain of the U.S. men’s gymnastics team, Vidmar led the team to its first-ever gold medal in 1984. That same year, he also captured the gold by scoring a perfect 10 for his pommel horse routine and won silver in the all-around men’s competition, making him the first American to medal in that category.

No doubt, Vidmar knows something about winning. But he also knows something of faith, loss, struggle, and family.

While Vidmar did not have a chance to publicly share his faith during the Olympic Games, he did have many missionary moments. “Certainly as I would travel around, competing as a member of the U.S. team, I had a chance to room with a lot of great guys and great gymnasts, and you have conversations that over time lead to discussions on faith and discussions on scripture and things like that,” Vidmar says.

But Vidmar’s most significant conversion story came before his Olympic career. While attending college at the University of California, Los Angeles, Vidmar met a beautiful young gymnast named Donna Harris. “She wasn’t a member,” he recalls. “She was on the gymnastics team at UCLA, and I had a chance to share in her conversion process.”

As Vidmar and Harris’s relationship deepened and the two talked more about their faith and hopes, Harris became interested in the Church and finally asked Vidmar to baptize her.

“I baptized her and we were married in the temple about a year after her conversion,” Vidmar remembers. “That’s what made becoming a gymnast all that really mattered through my sport I met my eternal companion.”

Through all he’s experienced, Vidmar has realized, “Life is about facing challenges, and sometimes we win and sometimes we don’t. I lost a lot more competitions than I won.” But despite the glory, despite the wins and losses, Vidmar told the Deseret News that “my greatest joy in life comes from seeing my children find joy.”

Late in 2015, Peter Vidmar resigned as chairman of the USA Gymnastics Board of Directors—a position he had held since 2008—to prepare to serve as mission president of the Australia Melbourne Mission.

Image from deseretnews.com

Standing Alone

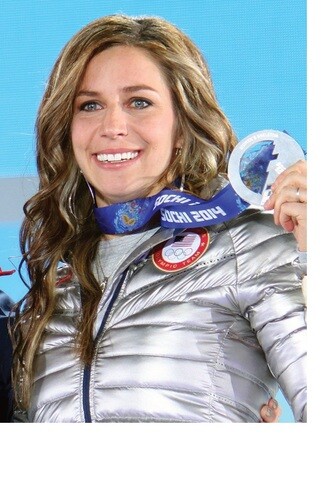

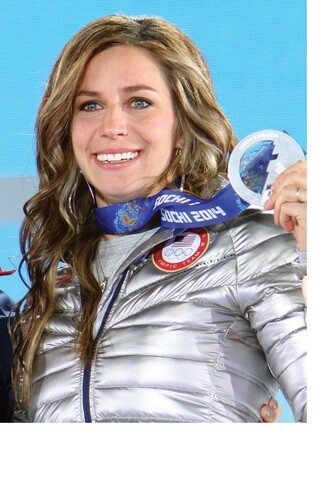

World Cup skeleton champion Noelle Pikus-Pace has experienced the heartbreak and elation of Olympic competitions.

Though favored to win gold heading into the Torino 2006 Games, she was unable to compete after a runaway bobsled rammed into her, fracturing her right leg.

But Pikus-Pace didn’t let this disappointment deter her: “The accident allowed me to see what I was made of physically, mentally, and spiritually,” she says, “and it was a confirmation that agency is why we’re here. Regardless of our situation, there is always a different way to look at things.”

By 2010, Pikus-Pace was ready for another run at the Olympics. But before proving her ability on a world stage, Pikus- Pace proved her standards to a nation at the Media Summit.

“This natio

nal event attracts every newspaper, magazine, television broadcast, charity foundation, and webcast with any interest in sports, health, or fitness. Athletes expected to do well in the Olympics received invitations to attend,” Pikus-Pace explains in her book, Focused.

During a photo shoot at the event, one of the assistants held up a short crimson dress with spaghetti straps, explaining that all the female athletes were taking pictures in red dresses to promote healthy hearts and healthy living. Pikus-Pace declined, and ultimately the assistant found a more modest, though less stylish, dress for her.

“When it came down to it, though, wearing the dress or not was a very easy decision for me to make,” Pikus-Pace shares in her book, “because I had already chosen to stand as a witness of God ‘at all times and in all things, and in all places’ (Mosiah 18:9).

“I had decided a long time ago that I wouldn’t let the vision and expectations of the world determine who I am or what I stand for.”

With unabated integrity, Pikus-Pace gave an excellent performance at the Vancouver 2010 Games, missing the medal podium by a mere tenth of a second. She decided to give her dream one final shot, coming out of retirement to compete in the 2014 Games in Sochi, Russia.

It was there Pikus-Pace took silver in women’s skeleton. As this medal, representing years of sacrifice, persistence, and family support, was being lifted over Pikus-Pace’s head, Latter-day Saints around the world noticed another silver pendant already on the Olympian’s neck: her Young Women medallion.

A stake Young Women president at the time, Pikus-Pace bravely displayed that simple memento of her faith throughout the Games. “I wasn’t trying to push anything on anyone, but I’m grateful that I can stand up for what I believe,” she shares. “I love the youth. I wanted them to know they can be great—that they can achieve anything they want to when they know who they are and what they stand for.”

Image from Getty Images