Siblings, parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins—they’re the first people I think of when it comes to my family. Ancestors, on the other hand, don’t usually make the list. While I know that a family tree consists of roots and branches, I too often forget about the roots—but a few years ago, I learned a story about my ancestors that changed all of that for me, and I thought I might share it in honor of Pioneer Day.

While I was a missionary, serving in a small town in Washington during the COVID-19 pandemic, my mission president encouraged us to take an hour each week to do family history—that’s where I came across the story of William Stewart and Sarah Thompson, my fourth-great-grandparents. Their story sounded like a script for a movie or the plot of a novel, and I was instantly captivated. I loved its fairy-tale beginning, the surprising plot twists and turns, and the obstacles in my ancestors’ way to find true happiness. But I’ve remembered the story because of their courage and faith. Born in the early 19th century, William and Sarah overcame tremendous trials to build a life together and had courage to put God first, even when it wasn’t popular or easy.

Learning William and Sarah’s story of courage, love, and faith has brought a greater sense of belonging to my life, and I hope that reading by reading it you will gain a greater motivation to learn your own family’s story and find greater connection to your family roots.

Author’s note: The information presented here has been collected in over a dozen family histories from William and Sarah’s great-grandchildren and great-great-grandchildren and pieced together from historical birth and census records. I’m thankful for the extensive records I had access to on FamilySearch.org, and for my extended family members who have kept and written down these stories. But I understand that for some groups, accessing records from even 150 years back is unrealistic. The Love Your Lineage podcast explores the complexities of family history and shows us how everyone, no matter our background or family situation, can make deep and powerful connections to our ancestors.

▶ You may also like: These women are making family history more inclusive—and they might help you love your own lineage

Secret Sweethearts

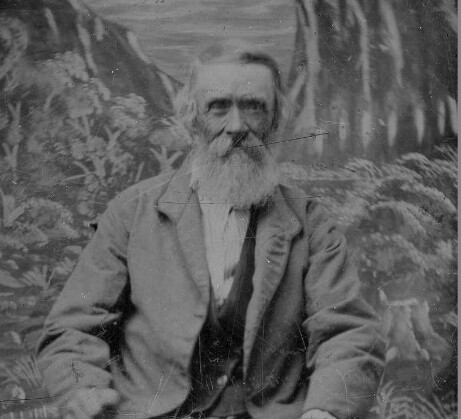

William Hugh Stewart Jr. was born in 1814 to Mary McLarty and William Hugh Stewart who were wealthy landowners is Campbelltown, Scotland. The Stewarts had a fine home, a stable of well-bred horses, and servants to tend their property. William Stewart Jr. was an excellent rider and lover of horses, and several histories recount that William—a tall, brown-eyed, brown-haired young man—could place a shilling between his boot and saddle stirrups, jump a five-rail fence on his horse, and land on the other side with the shilling in the exact same place.

Sarah Thompson had a very different childhood in Atrium, Ireland. Born in 1821, Sarah lived in very humble circumstances—her parents, Sarah Lyons and Samuel Thompson, had little money to spare. When Sarah was young, the Thompsons moved from Ireland to Campbelltown, Scotland, where Sarah—a shorter girl with auburn hair and blue-green eyes—met William Stewart Jr. The two attended school together, played together, grew up together—and their friendship eventually grew into love.

But unlike William, Sarah had to work and contribute to her family’s income and at times was a maid in the Stewart household. Even though the income was likely a blessing to Sarah at the time, it brought her relationship with William under the watchful eye of Mary McLarty Stewart, William’s mother. When Mary, a very proud woman, discovered the attachment between William and Sarah, she schemed to separate the two—the very last thing she wanted was for her son to marry a poor working girl.

One day, Mary invited Sarah to visit a distant parish with her, but instead she took Sarah to a remote dressmaking school and promised to fetch her after a time. This separation, Mary hoped, would end the unsuitable attachment between the maid and her son. Little did Mary know that her efforts were in vain: William and Sarah had already secretly married, and William had forged his uncle’s signature on their wedding certificate.

For nearly a year, William searched for his wife, but his mother refused to reveal Sarah’s whereabouts. Only after William happened to cross paths with one of Sarah’s brothers and learned of her location was he able to take off on one of his horses to fetch her.

Sarah sat sewing at an upstairs window of the school when she recognized a familiar sound—it was the unmistakable jingle of William’s bridle-bit and riding habit, and it was approaching the school! The strain of being at the school for so long and the anticipation of seeing her husband for the first time in months overwhelmed Sarah, and she fainted. Sarah’s fainting spell created a commotion just as William arrived at the school, and he naturally followed the cries for help and—finally—found her.

When William learned what his mother had done to separate him from Sarah, he felt betrayed by his family. Fearing that the forgery on their wedding certificate would be discovered and another separation would occur, the young couple fled to Antrim, Ireland, Sarah’s hometown, to start their new life.

▶ You may also like: The pluck and luck of the Irish Saints: A brief history of the Church in Ireland

New Life and New Faith

Even though Sarah and William were probably relieved to be reunited and excited to build a new life, there was another obstacle in their path: William had grown up in the Scottish upper-class and had never learned any trade. Now he found himself in a different part of the country without a means to support himself and his wife. But William took the challenge in stride and secured work in a paper mill. He quickly became one of their best workers.

While living in Antrim, William and Sarah welcomed two children to the world: Annie (my third-great grandmother) in December 1839, and William in May 1842. In 1843 (or so), William and Sarah moved to Greenock, Scotland, where William and Sarah’s next four children would be born: Samuel (April 1842), Sarah (August 1845), Elizabeth (February 1846), and Hugh (March 1851). After Hugh was born, William and Sarah moved their family about 25 miles east to Glasgow, Scotland, where working conditions were better. It was in Glasgow that Sarah gave birth to their seventh child, Thompson (March 1854), and met elders from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

William and Sarah’s oldest child, Annie, was skeptical about the religion her parents were investigating, but she attended church meetings with them. Annie would later say that she attended because she liked the hymns and the singing, but that the Spirit was urging her on. William, Sarah, and Annie recognized the truth in the gospel message and were soon baptized, even though their decision meant persecution and loss of friendship.

But no amount of difficulty could keep Sarah, a very religious woman, from taking her family to church services and encouraging them to work toward the goal of traveling to Salt Lake City. Sarah desperately wanted to go to Zion so that her family could gather with the Saints and so that she and William could be sealed to each other and their children for time and all eternity.

After her eight child, Martha, was born in April 1857, Sarah contracted edema (in that time called dropsy), and her body was bloated with water—this is a common side effect of pregnancy, and it was, at the time, nearly untreatable. In an effort to improve Sarah’s health, the family moved to Alexandria, Scotland, to be nearer the seaside. But even the fresh air and quiet town couldn’t cure Sarah, and her condition worsened to the point that she was unable to leave her bed.

When Sarah knew that she would not live for much longer, she asked her family to gather at her bedside and urged them to go to Utah so that they could more fully live the gospel. She also asked her husband not to leave any children behind in Scotland when they immigrated, and she entreated Annie to promise not to marry until she could be sealed in the temple.

Sarah died in June 1857, just eight weeks after Martha had been born, leaving William with a promise to take their family to Zion. Annie, as the oldest, left her work in the paper mills to care for baby Martha, wash, cook, clean, and do all that was necessary for her father and younger siblings.

For the next five years, the Stewart family held on to Sarah’s faith and the promises they made to her as they worked to earn enough money to immigrate to Utah. When Samuel was 17 years old, he traveled to America before the rest of his family, worked as a plumber, and earned enough to pay for his family to cross the Atlantic while anxiously awaiting their arrival to Zion.

William and Sarah’s first son, William, did not accept the gospel and stayed behind in Scotland, but William Stewart kept his promise to his wife as best he could, crossing the plains in the Joseph S. Rawlins ox team company with six of his children and reaching the Salt Lake Valley in September 1864.

When the Stewarts reached Salt Lake City, Annie soon went to work in a paper mill—that is where she met Andrew Walker Heggie, my third-great-grandfather. On February 3, 1865, she married Andrew in the Endowment House in Salt Lake City, keeping the promise she had made to her mother to wait to marry until she could be sealed. Annie Stewart and Andrew Heggie would go on to settle in Clarkston, Utah, and remained members of the Church throughout their lives. Their stalwart example of faith has blessed—and continues to bless—the lives of their descendants.

Finding Connection

William, Sarah, and Annie’s stories of courageous faith and commitment to the gospel humble and inspire me. Learning their story has been such a joy for me, but I haven’t always felt this way about family history. For a very long time, whenever I heard someone mention family history, I immediately thought: “Boring.” But now I’ve seen that nothing could be further from the truth. Elder Gerrit W. Gong’s April 2022 general conference message taught me that even though the importance of recording family history and records cannot be understated, there is so much more to family history than that.

In his talk, Elder Gong encouraged everyone to learn the stories of their ancestors. “Our ancestors deserve to be remembered. … Gather their photos and stories; make their memories real. Record their names, experiences, key dates. They are your family.” He also promised that “connecting with our ancestors can change our lives in surprising ways. From their trials and accomplishments, we gain faith and strength. From their love and sacrifices, we learn to forgive and move forward.”

As I think on what I’ve learned from William and Sarah’s story, I see the power of Elder Gong’s words. I learn forgiveness from William, who forgave his mother’s mistreatment of Sarah and reconciled with her in the early years of his marriage. I learn about courage from Sarah, who accepted the gospel when she felt the whisperings of the Spirit and encouraged her family to do the same. I learn patience from their daughter, Annie, who immediately stepped into the role of caregiver for a newborn baby and sacrificed countless hours of her time to provide for her family.

Like all families in every generation, the Stewarts had their trials, and I feel sad to think of the family’s devastation when Sarah died at only 37 years old, leaving her eight children and husband behind. But I was comforted when I read these words from Elder Gong: “In all our generations, Jesus Christ heals the brokenhearted, delivers the captives, sets at liberty them that are bruised” (emphasis added). For those who struggle, Jesus Christ is there, no matter the date or year. I’m so glad His power was present in Sarah, William, and Annie’s lives, and that it’s something that I can feel today too.

Ever since I can remember, I knew that my name, Sarah, was an old family name from my dad’s side that has been passed down from generation to generation. But I feel so much closer to one of my namesakes after learning her story. Elder Gong said, “As we discover our story, we connect, we belong, we become.” Even the smallest act of learning about a woman with whom I share my name has given me a stronger connection and sense of belonging with my ancestors.

But when I reach the next life, I hope that a name isn’t the only thing that I share with my fourth-great-grandmother. I hope my faith is strong like hers, that my love for my family is unyielding, that my trust in the Lord is absolute, and that I’ll always have the courage to cling to the truth—no matter what.