I disliked hearing pioneer stories when I was growing up. Stories of crossing the plains, losing children, and then coming into great blessings seemed to have little to do with me, a young Black girl. I spent the majority of my youth trying to prove to fellow Church members that I, too, belonged—that I also had a place within the Church and the gospel.

Yet that was before I learned that I was raised by a living pioneer, my mother, Sareta Dobbs. I had always known that my mom had joined the Church “back in the day.” She joined before she could enter the temple or serve a mission due to the devastating priesthood and temple restriction. She joined the Church before she was considered a “valiant” spirit (an idea based on false teachings at the time).1

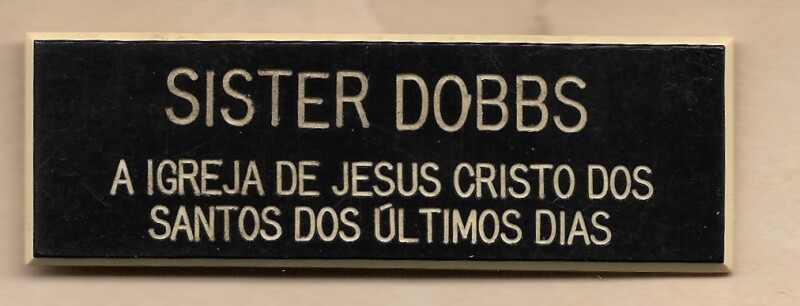

Honestly, if my mother had it her way, the story of her life in the Church would die with her; she doesn’t see her life as anything spectacular or special. A quiet and introverted woman, she rarely went into details about herself or her mission. It was when I, as a teenager, started nosing through old photo albums and journals that she told me something I never would have guessed: my mom was the first Black woman to receive a mission call for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Spiritual Beginnings

Raised in her pastor grandfather’s church—Eastside Church of God in Christ in Wichita, Kansas—during the race-conscious 1960s, my mother always had an interest in spiritual things. That interest led her at a young age to ask a Sunday School teacher two probing questions:

“Where do people go when they die?”

“Nowhere, they’re just dead,” the teacher replied.

“Well, where do we come from?”

The teacher gave an odd look, then responded: “Nowhere.”

The answers were not only unsatisfactory, but they also did not ring true to her. In a church that taught that one either went straight to heaven or hell, Mom became worried about her salvation. She recalls, “When I was 9 or 10, I prayed and prayed to be saved. I expected something to happen, like being so overcome by the Spirit I would fall over. But nothing happened, and I thought I hadn’t been saved.” She felt and hoped that the truth was out there, but she didn’t know where to find it.

As the 1970s proceeded, Mom momentarily found agnosticism to be a comfortable place. “My thought process was that if there was a God, He just didn’t care about what happened to people.”

Fast-forward to 1975. After some travel, Mom landed in Stockton, California, where she attended courses at the local community college. One of the classes Mom enrolled in was printing, where she became friends with a woman named Joyce. One day Joyce arrived to class in a dress, which puzzled my mom as printing class was messy. As it turned out, Joyce was the Relief Society homemaking leader and was getting ready to teach the sisters how to make a one-seamed dress. Intrigued, my mom attended the homemaking meeting and soon afterward began taking the discussions with the missionaries.

It was when she was taught the plan of salvation that she finally found the answers to the two questions she’d asked her Sunday School teacher years before. “When they told me that I am a spirit daughter of God and He loves me, my heart was pierced, and I knew it was true.” She knew she had found the gospel of truth for which she had been searching.

Remaining Steadfast

Mom officially became a member of the Church in May of 1976 at the age of 21. Desiring to share the gospel with all who would listen, and knowing that as a new convert she would need to wait to serve a mission until a year after being baptized, Mom prepared herself. She enrolled in institute classes, studied the Book of Mormon extensively, and read Church literature.

When her one year of membership was attained, she scheduled an appointment with her bishop and told him of her desire to serve a mission. Her bishop answered that he would have to consult with the stake president regarding Mom’s request. At their next appointment, the bishop told her that she would not be able to serve a mission because, as she was barred from entering the temple due to the priesthood and temple restriction, she could not be endowed. Logical as always, Mom countered that in countries without temples, unendowed missionaries were allowed to serve.2 The bishop gave no response and ended their appointment.

After finishing her associate degree, Mom returned home to Kansas, where she planned to continue her activity in her new ward. As she prepared to attend the first Sunday home, my grandmother asked, “What if they don’t accept you?” Mom replied firmly, “It’s not their church,” expressing her conviction that the Church belonged to God and not human beings.

Mom’s presence as a Black woman was accepted by some and was also a great discomfort to others, some of whom refused not only to acknowledge her but also wouldn’t share a hallway or sidewalk with her. Despite being refused her mission request and having to deal with some unkind members, Mom chose to stay. She knew how God felt about her and felt that one day, the Church would enable all of God’s children to receive the fulness of the gospel.

A year later, Mom felt inspired to move to Utah, a place she had neither visited nor had any desire to go. However, Mom followed the prompting, hitched a ride with a ward member, and found a host family in Utah. She had only been in Utah for a week and a half when, upon returning home from job searching, she was met at the door by her host mother, who excitedly asked, “Did you hear?”

“Hear what?” Mom asked.

“President Kimball has announced that Blacks can hold the priesthood!”

Called to Serve

Mom continued to muse upon the reason she had felt impressed to move to Utah when the next weekend she attended a stake conference where Elder Neal A. Maxwell presided. Although the hope of serving a mission had faded, she walked up to Elder Maxwell after the meeting, shook his hand, and asked for a blessing in the hopes that she might discover what the Lord wanted for her in Utah. Without hesitation, Elder Maxwell agreed and blessed Mom that her tongue would be loosed in bearing her testimony to others, especially her own people. After fasting and prayer, she concluded that it was time for her to serve a mission and scheduled an appointment with her bishop. Upon her arrival, the bishop told her: “I was just getting ready to call you and make an appointment when I saw that you had already scheduled one. Elder Maxwell called me and said that he feels you need to serve a mission.”

Mom began her paperwork and preparations right away, and on July 17, 1978, she received her mission call to the Brazil Rio de Janeiro Mission. She began to prepare earnestly by memorizing the story of the First Vision and learning about the country of Brazil. She was endowed in the Salt Lake Temple on September 1, 1978, and entered the Missionary Training Center (then known as the LTM or Language Training Mission) on September 28.3 It was while she was there that she learned from fellow missionaries that Elder Bruce R. McConkie had mentioned her in a recent CES Symposium, saying, “We have already called our first Negro sister, assigned to the Brazil Rio de Janeiro Mission.”4

The most important and most repeated memory Mom has shared about her mission was that while serving in Brazil with so many missionaries of diverse backgrounds, Mom lost her race consciousness. When a woman was chatting with her and her companion, the woman remarked that Mom was “pretty for a Black girl,” and Mom gave a start. “I had completely forgotten about race while I was there,” she says. “When the woman said that, I realized, sadly, that I was going to have to go back to the States and be race-conscious once again.”

It wasn’t until 2018 that Mom told us that she knew Elder Ulisses Soares, as she had served with him in Brazil, and that his wife, Sister Rosana Soares, had been one of her companions, though the three were out of contact for many years.

“Your mother,” Elder and Sister Soares recently wrote to me, “was a sweet and marvelous disciple of Christ. We have great memories of our service together, and we rejoiced last year when we finally had our mission reunion and we saw your mother for the first time again after so many years. What a great and rejoicing reunion.”

Even after hearing her story, knowing she was the first Black woman to receive her mission call, I still ask my mother: “Why would you ever join a Church that clearly did not want you?” (I ask this knowing that at that time in the Black community, the priesthood restriction was viewed as a means of keeping Black people out of the Church.)

As always, my mom’s response is, “Because, I found truth.”

Still incredulous, I recently asked her, “Didn’t your faith waver? People wouldn’t look at you, you couldn’t go to the temple— didn’t you ever think, ‘Maybe this ain’t the place for me’?”

My mom, firm and quiet, replied: “Never. Ever.”

My mom served her mission and returned to the States, where she married, raised three children in the gospel, obtained multiple degrees, and has continued to be faithful. Were our roles reversed, I am not sure that I could have done what my mother managed to do. I couldn’t have joined a church that barred me from the fulness of the gospel—a gospel that teaches a love for all of God’s children. These days, I am often frustrated by the racism and sexism I encounter at church. Sometimes it feels like a little too much for me to bear and I feel like calling it quits.

But then I remember my mom. I picture her with Elder Maxwell. I remember her kneeling in daily prayer during my childhood. I see her standing her ground when fellow members wouldn’t even look at her. So, I stay.

I stay because, like my mom, I love Jesus Christ. I love the gospel.

I stay for every person who has ever felt that they don’t belong in the Church or in Church history.

I stay for every person who feels unseen.

I stay because in the gospel of Christ we all belong.

▶ You may also like: First Black missionary to serve after 1978 revelation on priesthood explains why attempts at explaining ban do more harm than good

Notes

- The Church’s Gospel Topics essay “Race and the Priesthood” addresses the once common theory in which “blacks were said to have been less than fully valiant in the premortal battle against Lucifer and, as a consequence, were restricted from priesthood and temple blessings.” However, “today, the Church disavows the theories advanced in the past that black skin is a sign of divine disfavor or curse, or that it reflects unrighteous actions in a premortal life; that mixed-race marriages are a sin; or that blacks or people of any other race or ethnicity are inferior in any way to anyone else” (topics.ChurchofJesusChrist.org).

- For example, see Scott Taylor, “Elder Soares Dedicates Fortaleza Brazil Temple,” Church News, June 3, 2019, ChurchofJesusChrist.org.

- My mother spent several weeks in the LTM to learn Portuguese. After she arrived, Mary Frances Sturlaugson, another Black woman who was not learning a foreign language, reported to the LTM, completed her training, and left for her mission a couple weeks before my mother.

- Bruce R. McConkie, “All Are Alike unto God” (CES Religious Educators Symposium, Aug. 18, 1978), 5–6, speeches.byu.edu.