Editor’s note: This article was the cover story of the July/August 2022 issue of LDS Living magazine.

Marguerite Gong was packed and ready to go. It was 1981, and with a camera, tape recorder, and a suitcase full of clothes in tow, the 20-year-old was ready to help fulfill a promise her grandfather had made many years before. According to her father, that promise had its roots in a small family village in southern China where her 30th great-grandfather, First Dragon Gong, had come to live in AD 837. The people there survived by growing rice and taro and raising pigs. But as the sun set on one generation and rose with the next, life in the village remained very much the same and few technological advancements penetrated its borders.

Centuries came and went; crops were planted and harvested. One day, however, Marguerite’s grandfather made a fateful decision to leave his homeland in search of opportunity for his posterity. Promising to return, he intended to eventually help bring electricity back to the family village.

Settling in a rural town in California, Marguerite’s grandfather and grandmother raised six children, but their path was not an easy one—the couple didn’t speak English and worked constantly, opening a hand laundry and a grocery store to make a living. But while they were never able to return to their family village, they found comfort in knowing that every worthwhile dream required sacrifice.

With a camera, tape recorder, and a suitcase full of clothes in tow, the 20-year-old was ready to help fulfill a promise her grandfather had made many years before.

So when Marguerite went to the village with her father and brother as her grandfather had once planned, the experience left an indelible impression on her heart. She recalls lying on a hardwood bed with a thin mattress made of straw as her second cousins asked about her life. They peppered her with questions of what it was like to have teachers, books, and libraries. Having never been beyond an hour’s bicycle ride past their village, they listened eagerly as Marguerite tried in broken Mandarin to describe mountains, oceans, elephants, the Parthenon, and the Louvre Museum in Paris.

In contrast, her relatives gathered sticks for fuel, owned only two outfits, and had no running water. But the young woman from California could see that their life was nevertheless abundant, as they had a sense of identity from belonging to a family through generations of time. The experience affected her deeply.

“That was just life-changing—it still brings emotion to me,” Marguerite says. “As a child of a schoolteacher and a professor in Palo Alto, my life was more abundant than I could realize.”

That family village is now a thriving, modern place that Marguerite has since visited with her family. But the lessons she learned on that first trip to China helped lay a foundation for other important experiences in her life, including her studies at Brigham Young University, Harvard, and the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy.

Her passion for technology and humanity continued into her 20-year career at Stanford, during which time she was actively involved in helping nations like China, Japan, South Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan, and countries in Europe and Latin America to use technology to advance their economies and societies. She’s co-edited three books, Greater China’s Quest for Innovation, Making IT: The Rise of Asia in High Tech, and The Silicon Valley Edge: A Habitat for Innovation and Entrepreneurship. A political economist, she’s also been interviewed by Bloomberg and cited by The New York Times, Forbes, and San Jose Mercury News.

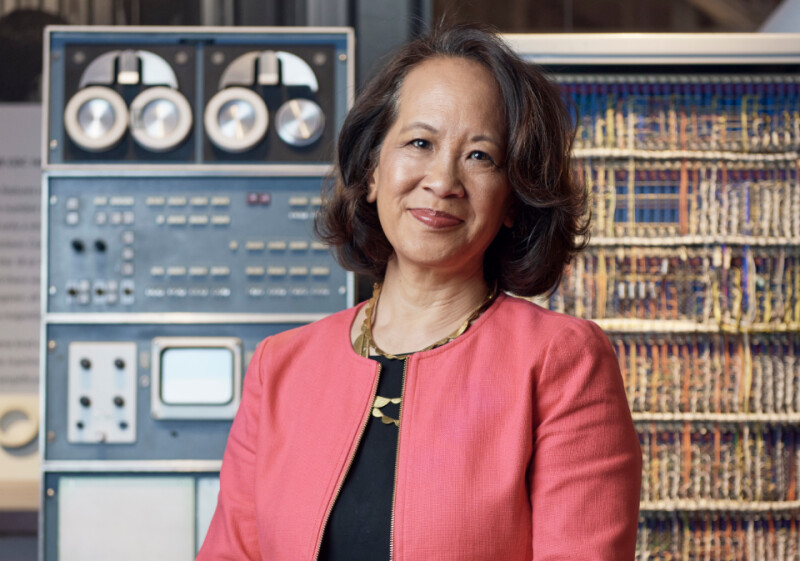

Now the vice president of innovation and programming at Silicon Valley’s Computer History Museum, Marguerite focuses her work on innovation across the museum, including events, education, diversity, and inclusion. She is also the director of the museum’s Exponential Center, which captures the past and considers the future of innovation and entrepreneurship. And yet, among these many accomplishments, Marguerite had her own personal challenges to face as she fought breast cancer and endured the many chemotherapy and radiation treatments that came with it. But as a woman who believes that nothing is more important than her faith and family, Marguerite lives with a mindset she saw exemplified in that Gong family home with a dirt floor and a single light bulb: abundance. So no matter how difficult the obstacle, or how great the opportunity, she determined then to live her life with the conviction that the blessings she had been given were immeasurable—and she would always strive to live up to them and share them with others.

The Most Important Thing

Ever since she was a teenager, Marguerite has been driven to enable abundance in the lives of others, which would become an emphasis in her career. She studied Humanities and Asian Studies at BYU and her curiosity was piqued by the question of what helped civilizations advance—or fall behind.

After graduating, Marguerite studied East Asian Studies at Harvard, where she met fellow student Russell Hancock. They were in the Harvard-Yenching Library in between his Japanese class and her Chinese class when they noticed each other.

“There she was, sitting in front of me, … this wonderful person with so much radiance. And I just had to know her. My gosh, I had to know this woman. And so I kept frequenting that library, and so did she, and that’s how our friendship formed,” Russell says. “She was just so remarkable, so deep, so intelligent, so insightful. But then on top of all that, beautiful, radiant … [there was] this ebullience about her. This joyfulness. Which, you know, in the middle of a Boston winter, that’s a really nice thing.”

Marguerite and Russell were married 18 months later in 1984 in the Oakland California Temple. As they began adding to their family, the couple consciously chose to have a full partnership in both parenting and professions. So together, they made their family a priority and took a “rich, wonderful, intertwined, and integrated” approach in choosing careers that would be flexible and allow them to put their children first, Russell says.

After marrying, Marguerite studied at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy and developed a fascination for how technology, innovation, and entrepreneurship help economies advance. She then put that knowledge to good use at Stanford, traveling to China at least 15 times as she collaborated with some of the most prestigious universities in the nation. Additionally, she advised government leaders in building high-tech regions in cities like Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen, as well as in nations around the world.

Throughout her career, Marguerite has been driven with a purpose that, second to family, is her mission in life—to bless humanity through technology. But in recent years, that mission has taken on a new dimension through her work at the Computer History Museum (CHM).

Humanity and Technology

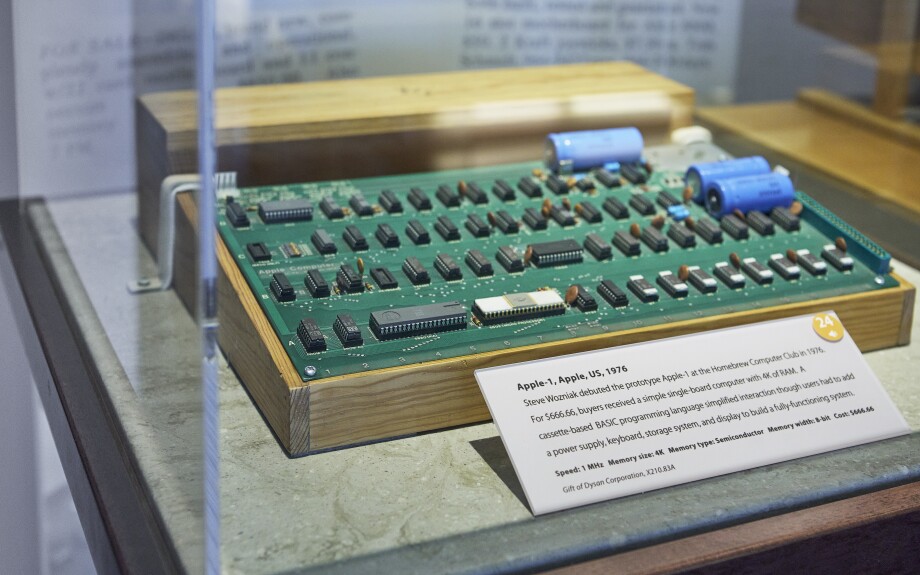

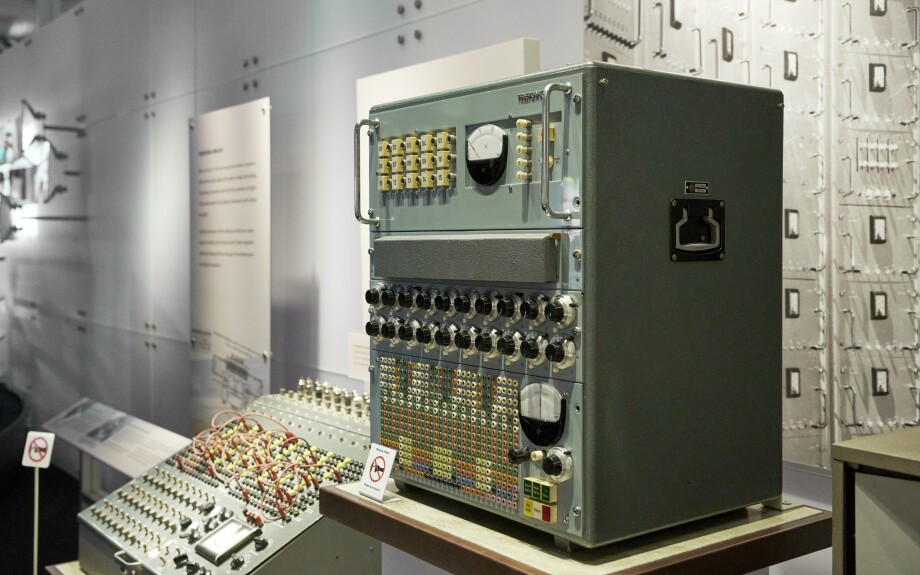

Located in Mountain View, California, CHM boasts the largest collection of computing artifacts in the world, with items like calculators, robots, and microelectronics on display—but there’s much more to the organization than exhibits. The museum’s broader purpose is to learn from the computing past to understand the digital world today and to shape a better future.

As vice president of innovation and programming at CHM, Marguerite is responsible for the overall direction and strategy of the museum. She leads a center in the museum related to all things entrepreneurship and helps collect the stories of technology changemakers and their artifacts. Additionally, she works on the museum’s growth through funding and partnerships and oversees matters of education and diversity.

Dan’l Lewin, president and CEO of the museum, says that Marguerite has a talent for seeing how technology can improve the human condition, and her vision for the organization has proven invaluable.

“In many ways, I would tip my hat to [Marguerite] and her creativity for helping me and the institution chart its course into a more relevant future with a broader audience,” he says. Part of that audience reaches hundreds of thousands of people in events that Marguerite organizes. But whether she’s gathering museum leaders to discuss diversity and inclusion; bringing together journalists, academics, and policy makers for conversations; or holding a prize ceremony for changemakers like Sal Khan of Khan Academy with Bill Gates giving a tribute, Marguerite always focuses her work on how technology can be used positively.

“I’m a techno-optimist because I believe technology can and has been a power for good. I also recognize that it can have a lot of negative consequences, but I want to make sure that people see both sides of the coin and realize that [technology is] a tool that people create and also harness. And that’s part of my mission—to help people both feel the responsibility and the opportunity to make decisions in a better way,” she says.

For example, Marguerite seeks to help creators of technology better serve people around the world.

“Unintentionally … software engineers who are creating algorithms to discern faces did it based on a sample of people that look like them, who are primarily white males,” she says. “We know that [artificial intelligence] algorithms for a time were biased against women and people of color. And so those kinds of issues are equally important for our museum … to make sure that the creators of technology are doing it in a way that’s going to be beneficial, inclusive, … equitable, ethical, and empowering.”

Give Me This Mountain

While Marguerite is dedicated to her personal calling of improving humanity’s relationship with technology, she similarly prioritizes her church callings—one of which especially prepared her for the most spiritually refining experience of her life.

In 2005, Marguerite was serving as girls camp director and was so inspired by that year’s theme, “Give me this mountain” (Joshua 14:12), that she decided to ask God for the same thing.

“I felt moved to make the commitment to ask God to ‘give me this mountain,’” Marguerite recalls. “As I prayed about it, I said, ‘I have no idea what that might be. But I’m ready and willing to climb a new mountain.’ And I felt moved to read my scriptures with more purpose and be more reflective and prepare … to summit a new mountain, and then wait.”

So the following year, Marguerite was surprised but not totally shocked when she learned what her mountain was. On October 7, 2006, she recalls standing in her family room when she received a phone call from a doctor. The doctor informed Marguerite that she had breast cancer that had spread to some lymph nodes, so she would need to prepare for surgery and treatment.

The journey that followed included four surgeries, six rounds of chemotherapy, six rounds of radiation, and additional medication. At first, Marguerite had just one drawer with her medication in it. But then that drawer turned into a cupboard, which became a closet full of medicine. In one year, the number of doctor appointments, scans, and infusions totaled more than 175, and Marguerite eventually reached the point where she knew which needle was her favorite for an IV.

“There were times that I couldn’t write. I lost my memory. I lost my ability to process. … It was a time that I certainly wasn’t feeling very abundant. I felt empty and spent, depleted, drained, exhausted,” Marguerite recalls.

One day in particular stands out in her memory. “I had this shortness of breath, pain in my chest, just total confusion, difficulty focusing. It felt like previous rounds of chemo, but maybe worse. And I was really afraid. I was so weak. I couldn’t talk. I couldn’t call out. … I couldn’t do anything. All I could do was just be,” she says.

She felt a darkness taking over her as she started lapsing into unconsciousness. But then something roused her from the dark.

“I was given a remarkable gift: I heard the sound of one bird chirping outside. It was intermittent. Maybe it was on the balcony. I couldn’t see, but I could hear it clearly and persistently,” she says, noting that the sound kept her conscious enough that she remembered to keep breathing.

Later that day, Marguerite was rushed to the hospital, where doctors determined she had a spontaneous pneumothorax, or collapsed lung, and her body had been shutting down due to lack of oxygen. After that harrowing ordeal, Marguerite was having an MRI. As she started to pray, the repeated clicking sound of the machine receded and she heard a calming humming sound that reaffirmed her of God’s tender awareness of her.

Marguerite earned a deep measure of serenity, acceptance, and simplicity through facing the many complexities in her cancer journey.

“And then I realized [the sound was actually] voices. … It was hard for me to make out [what] they [were] saying, and then I heard my name. I realized that they were praying for me, and I strained to recognize them. Some were familiar voices of loved ones I’d been aware of who had been praying for me. But what astonished me is that there were so many more voices—people that I hadn’t talked to recently, a BYU friend, a former board member, a neighbor. … I knew without a doubt from those experiences … that God was fully aware of me and through His grace we often can hear or feel reminders of His bounteous love,” she says.

Marguerite earned a deep measure of serenity, acceptance, and simplicity through facing the many complexities in her cancer journey.

“My wife was refined by cancer,” Russell says. “It shaped her in very deep and spiritual ways. And she emerged from it a different creature—more herself, but more refined.”

Even though treatments depleted her, Marguerite found strength in relying on other people’s abundance. There was also a kind of beauty, she says, in simply being and in concentrating on one breath at a time.

“I learned that an abundant life like this doesn’t come packaged or premade. It’s not something I can order from Amazon or have delivered on my doorstep the next day. … I learned about [this kind of abundance] through grit in the face of hardship and sorrow and humble recognition of God’s abiding goodness and grace,” she says. “Certainly I felt the sweet, the honey, far outweigh the bitter—and there was plenty of bitter—but there was this abundance that could be in being with God.”

Building Bay-Area Bridges

In finding abundance with God, Marguerite strives to define her life by the two great commandments—to love the Lord with all her heart and to love her neighbor. In fact, Marguerite takes the commandment to love her neighbor so seriously that 34 years ago she helped start an annual nativity display in her hometown of Palo Alto called The Christmas Créche Exhibit to build bridges among different faiths in the community.

“At the time, our neighbors didn’t believe that members of the Church believed in Christ. And that was a time of great animosity, criticism, and friction because of this inaccurate understanding about our beliefs,” she says. “Rather than going head-on and arguing, we thought, Why don’t we just show what our beliefs are and lovingly invite everybody to come?”

The project started out small, with tens of nativities on display in a local chapel. But now, thousands of nativities are offered from other churches and individuals throughout the Bay Area and beyond. Each year the team selects a collection to feature, so the exhibit is always changing, reflecting the diversity of God’s children who all have a connection to the Savior. The exhibit is like a high-quality museum, with marionette shows, live nativities, crafts, multimedia materials, and guest artists and sculptors. Rooms are themed with Asian-inspired sets and traditional European scenes, and even machine parts and circuit boards are used to create Silicon Valley–style nativities.

The last time the exhibit was held in person, over 10,000 people attended over five days, with entries in the guestbook from people in 78 California cities, 18 states, and 10 countries. More than half of the guests came from other faiths and backgrounds. After the pandemic hit, the Menlo Park Stake and the Los Altos Stake decided to hold the event virtually. Suddenly, tens of thousands were able to participate. In 2022, the exhibit will continue its virtual presence while returning to its beloved in-person format.

“These are stories of people from so many places that we would never have been able to have captured or shared without technology,” Marguerite says. “When we use technology thoughtfully, prayerfully, intentionally, strategically, it can have power for good … [and help us] share the gospel.”

A Rare Calling

Marguerite and Russell also share the gospel by serving as diplomatic liaisons on the Church’s communication council, which is part of the Public Affairs department. On the council, they help build bridges of understanding and cooperation between the Church and consuls from around the world who live in California. As part of that effort, each year Marguerite and Russell host a briefing in Silicon Valley for consuls from 20 to 30 countries.

The objective of the event is to introduce consuls to Latter-day Saint leaders in business, technology, finance, academia, and the community. These leaders share their relevant expertise with the consuls and include why being a member of the Church is meaningful for them and give their views on being part of a global community.

“It is the most fun thing in the whole world,” says Matthew Ball, who works as the Church’s Director of Public and International Affairs in the North America West Area. He remembers one year when Marguerite and Russell brought in the creator and developer of the algorithm that prevents midair collisions for aircraft around the world. “Everyone’s like, ‘Oh, my heavens, where do you find these people?’” he says.

This year’s briefing focused on emerging from the pandemic and discussed topics like mental health and wellness, running world-class health care, and researching new vaccines. Marguerite enjoys how the briefing brings faith and the secular together in a natural way.

“Sometimes faith and learning are different, but often they’re actually interwoven and braided together in ways that we couldn’t have foreseen when they started,” she says. “But over our lifetimes, [we] can see how they become braided together in the Lord’s time and will to serve His purposes.”

Abundance

Earlier this year, Marguerite asked Russell how he would like to celebrate his birthday. In response, he joked that he wanted to travel to a villa in Tuscany surrounded by their three children and three grandchildren, eating Mediterranean cuisine. They both laughed at the idea. But then when his birthday arrived, Marguerite surprised her husband with a pizza oven powered by a propane tank. They set it up on a table outside and the whole family came to celebrate.

“There are my kids shoveling pizza into a pizza oven that heats up to 900 degrees, and she’s turned our full backyard into Tuscany,” Russell recalls. “It was the most rich and wonderful thing. She brought Tuscany to me. So that’s what we mean by abundance. Anything’s possible.”

Abundance feels particularly rich to Marguerite as she’s watched her family grow—a blessing that is all the more meaningful since her battle with cancer—and feels strongly that life is a gift and age should be celebrated.

“Who could have imagined the unspeakable joy of seeing what happens over time as your family multiplies and becomes more abundant?” she says, including her extended family in those numbers. “They’re meant to be loved fiercely and protected and invested in.”

Marguerite often reflects with gratitude on previous generations, like her grandfather and her 30th great-grandfather First Dragon Gong, who laid foundations for her family before her. She remembers her love for her Chinese heritage while researching how technology can bless people worldwide. And she brings the world to her loved ones in ways great and small—even if it means creating a bit of Tuscany in her backyard.

Always innovative, Marguerite plans for her future family as well—because while she may not live off the land in the same way her ancestors did, she can plant seeds for coming generations just the same.

“I hope that my family feels that my greatest joy and efforts have been to and for building our family,” she says. “[I hope] to honor those people who have come before and [to find] concrete ways [to] plow the ground and plant the seeds for generations to come, … maybe my great-grandchildren or great-great-grandchildren I haven’t met. I hope that in some way my life will contribute to that.”