An Extraordinary Call

In 1951, Martha Ann Stevens Howell and her husband, Abner, were called to serve an extraordinary mission, one that was never again duplicated. For much of the Church’s history, from the mid-1800s until 1978, the Church did not ordain men of black African descent to its priesthood or allow Black men or women to participate in temple endowment or sealing ordinances. This helped reinforce the racial inequity and oppression already present among Church members in the nineteenth century.

Because of this, it was difficult for many Black individuals to feel a sense of belonging among the Latter-day Saints, and Church leaders were concerned that very few descendants of Black pioneers had stayed active in the Church. Simultaneously, they observed that other Christian denominations, including the Methodists and Baptists, had successfully established Black congregations. The practice of segregation was common in the United States in the 1950s, and though the Church had never had a policy of segregated congregations, leaders wondered if Black Latter-day Saints would be interested in something similar. They called Martha Ann and Abner, both Black Latter-day Saints, to serve in the Southern and Eastern states to assess the needs of Black Church members and to investigate the possibility of establishing Black congregations.1

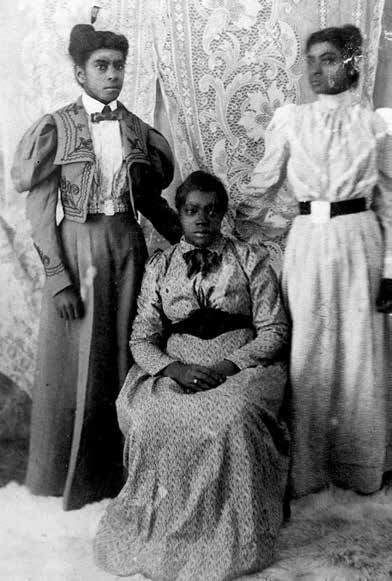

Martha Ann and Abner were perfectly suited for this mission. They were known for their friendliness, work ethic, and strong testimonies of the gospel. Both had been harmed by racism, and Martha Ann had a deep desire to change such prejudices.2 Before moving to Utah, Abner’s parents had been enslaved, and Martha Ann had been born in 1875, just ten years after the Civil War had ended. Martha Ann’s family was well-known and respected in the Salt Lake Valley. She was named after her maternal grandmother, Martha Vilate Flake, who had been enslaved and migrated to the West with the Mississippi Saints. Martha Ann’s grandfather Green Flake had been baptized and came across the plains, while still enslaved, with the very first pioneer company in 1847. He was among the first to enter the Salt Lake Valley and was among those who heard Brigham Young say, “This is the right place.” Green and Martha Vilate were married in Salt Lake City after Green had paid Martha’s enslaver for her freedom. Both Green and Martha had faith in God’s plan, and upon Green’s death, a newspaper wrote that he had “always remained a firm believer in the Mormon faith.”3

Although Martha Ann’s family descended from the same group of hardworking pioneers as White Latter-day Saints, some Church members had discriminated against her mother because of her skin color and declared they wouldn’t attend services if a Black person was present. Because of this racial discrimination, Martha Ann’s mom quit attending church meetings. Amid such racism and abuse, Martha Ann, and a handful of other descendants of Black pioneers, still chose to remain active in the Church.4

“He Inviteth All To Partake”

When Martha Ann and Abner left on their mission to the Southern and Eastern states, the presiding bishop of the Church, LeGrand Richards, wrote a letter for them to present to the congregations they visited. Because of common discriminatory attitudes in the Church and throughout the United States, it’s likely that some Latter-day Saint congregations would have been wary or unwelcoming of the Black couple; the letter introduced the Howells and assured Church members that the Howells were there on a Church-sanctioned mission. Richards explained that they had been asked to call upon the missionaries and Saints in the area and requested that the members accept the Howells with kindness and courtesy.

After visiting the Eastern states, Martha Ann and Abner traveled to Cincinnati, Ohio, where they met Len and Mary Hope. Martha Ann and Mary became fast friends. They were about the same age, and both were Black Latter-day Saint women. They understood what it was like to be disenfranchised and to experience racism within their chosen faith. The local branch president forbade the Hope family from attending the all-White Church meetings in Cincinnati. Despite feeling the pain of rejection, they met with the missionaries monthly in their home.5 Reflecting upon the Hope family’s situation, Abner said: “We found that society had creeped into religion. Most of the members lived across the river on the Kentucky side, and some of them did not want the Negro family to come to church.”6

That Sunday, the Howells and Hopes attended the Cincinnati branch. They presented LeGrand Richards’s letter, and Abner was invited to speak. In his remarks, Abner shared 2 Nephi 26:33, which reads: “He inviteth them all to come unto him and partake of his goodness; and he denieth none that come unto him, black and white, bond and free, male and female.” After the meeting, members of the congregation approached Abner and Martha Ann and shook their hands. One man said, “I didn’t know there were such things in the Book of Mormon.”7

At the end of their mission, Martha Ann and Abner concluded that segregated branches weren’t a sustainable option for the Church because of the small number of Black Latter-day Saints. Other Black Christian congregations were flourishing in the United States, but prejudice and false beliefs among the Latter-day Saints regarding people of African descent stymied the spread of the gospel among Black Americans.8 Although their mission wasn’t to preach, Martha Ann and Abner bravely stood up against such prejudice and taught gospel truths.

Embracing the Future With Faith

Martha Ann lived during a unique time in United States history— she was born shortly after slavery had been abolished and passed away just before the beginning of the Civil Rights Movement. In childhood, she was close with her grandparents, who told her stories of their enslavement.9 Martha Ann passed away on May 10, 1954, and exactly one week later, after years of political activism from many Black Americans, the US Supreme Court outlawed segregation in schools. Martha Ann stood with poise and purpose as a Black member of the Church. She sought for all to receive an education, had a gift for making friends easily, and raised her family in the faith despite the racism in the Church.10 Martha Ann’s daughter, Mary Lucille Bankhead, became the first Relief Society president of the Genesis Group, an organization created by Church leaders in 1971 to support and meet the needs of Black Latter-day Saints.11 Martha Ann’s posterity, along with many others, was affected for good by her testimony and her strength in her beliefs. 12

In 1971, three Black Latter-day Saints—Ruffin Bridgeforth, Darius Gray, and Eugene Orr—partnered together to garner more support for Black members of the Church. They expressed concern about the Church’s position on Black Latter-day Saints with President Joseph Fielding Smith. In response, the prophet asked then-Apostles Gordon B. Hinckley, Thomas S. Monson, and Boyd K. Packer to meet with these men. Consequently, on October 19, 1971, the Genesis Group was founded to focus on the needs of Black Latter-day Saints.13 Darius Gray said, “Genesis was, and is, a unique unit of the Church. We are like no other Church organization but our existence was brought into being by the direct actions of the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve.”14 The Genesis Group provides opportunities for fellowship, organizes devotionals and activities, and welcomes Black Latter-day Saints in an affirming environment. Group meetings often include a gospel choir as well as call-and-response testimonies.15 In 2021, the Genesis Group celebrated its fifty-year anniversary and continues to support thousands of individuals by fostering an accepting community where they can celebrate their collective identity. The president of the group since 2018, Davis Stovall, said: “And that is what Genesis is about. We celebrate our spiritual identity, which is our cultural identity. We put the Lord and Savior Jesus Christ first.”16

► You may also like: Why the Church created a special African American congregation over 50 years ago

She Did: Ordinary Women, Extraordinary Faith

Many of these women’s stories are not widely known, but they offer examples of faithfulness that can inspire us to be active participants with the Lord in directing our future.

Notes

- Brittany Chapman Nash and Richard E. Turley Jr., eds., Women of Faith in the Latter Days, vol. 4, 1871–1900 (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 103–4, 322; “Race and the Priesthood,” Gospel Topics Essays, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/manual/gospel-topics-essays/race-and-the-priesthood?lang=eng.

- “Martha Ann Jane Stevens Perkins Howell,” MormonWiki, last modified June 24, 2021, https://www.mormonwiki.com/Martha_Ann_Jane_Stevens_Perkins_Howell; Margaret Blair Young, “Abner Leonard Howell (1877–1966),” BlackPast, https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/howell-abner-leonard-1877-1966/; Nash and Turley, Women, 97, 99–100, 102–4.

- “Green Flake,” Century of Black Mormons, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah, https://exhibits.lib.utah.edu/s/century-of-black-mormons/page/flake-green#?#_ftn9&cv=3&xywh=346%2C137%2C3211%2C1472.

- “Martha Ann Jane Stevens Perkins Howell”; Nash and Turley, Women, 97–98, 102–3, 107.

- Nash and Turley, Women, 104.

- Kate B. Carter, The Story of the Negro Pioneer (Salt Lake City: Daughters of Utah Pioneers, 1965), 59.

- Nash and Turley, Women, 104–7.

- Nash and Turley, Women, 107; “Martha Ann Jane Stevens Perkins Howell.”

- Nash and Turley, Women, 107.

- Nash and Turley, Women, 97–102; Margaret Blair Young, “The Black Woman Who Served an Unprecedented Church Mission to Help Reduce Segregation, Prejudice in the Church,” LDS Living, February 19, 2019, ldsliving.com/the-black-woman-who-served-an-unprecedented-church-mission-to-help-reduce-segregation-prejudice-in-the-church/s/90299.

- Nash and Turley, Women, 97, 102.

- Nash and Turley, Women, 101.

- Michael Aguirre, “Ruffin Bridgeforth (1923–1997),” BlackPast, last modified August 29, 2016, https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/people-african-american-history/bridgeforth-ruffin-1923-1997/.

- “History,” Utah Area Genesis Group of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, https://www.ldsgenesisgroup.org/#history.

- Tad Walch, “LDS Church Reorganizes Genesis Group Leadership,” Deseret News, January 8, 2018, https://www.deseret.com/2018/1/8/20637984/lds-church-reorganizes-genesis-group-leadership.

- “The Genesis Group Gathers on Temple Square to Celebrate 50 Years since Its Creation,” Newsroom, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, October 23, 2021, https://newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org/article/genesis-group-50-years.